Russian military spending to rise & rise

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — written by Alexandra Prokopenko and Alexander Kolyandr and brought to you by The Bell. Our top story this week is a look at why Russian military spending is set to rise as discussions begin over this year’s budget. We also look at why the government is acting to weaken the ruble.

Five reasons why Russian military spending will grow

The Russian government this week began discussing next year’s budget. In last year’s budget, the assumption was that the situation would already be returning to “normal” by this point in 2024 and it expected that military spending would drop almost by a third in 2026. However, as the war in Ukraine drags on, this seems highly unlikely. Russian President Vladimir Putin shows no sign of backing down militarily, or politically, and Russia’s economy is fast becoming entirely dependent on record levels of military spending.

What’s going on?

Russia passes annual budgets covering a three-year period, and discussions about this year’s budget (which will cover 2025, 2026 and 2027) began this week in the government.

Last year’s budget envisaged that total revenue in 2025 would be 33.5 trillion rubles ($368 billion) and that there would be 34.3 trillion rubles of spending (which meant a deficit of 0.83 trillion rubles). Since then, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov has said that another trillion rubles will need to be spent in order to carry out the pledges Putin made in his state-of-the-nation address earlier this year. And that’s unlikely to be the only unplanned expense. We don’t have up-to-date figures, but there are lots of reasons to think the 2025 spending figures will have to be drastically revised in this year’s budget.

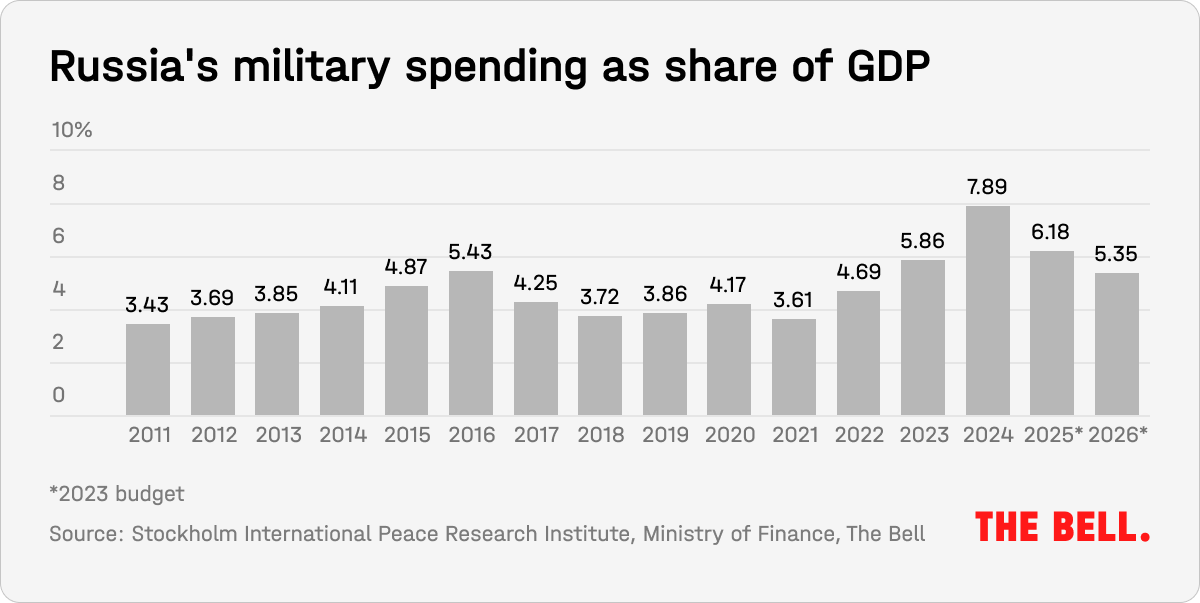

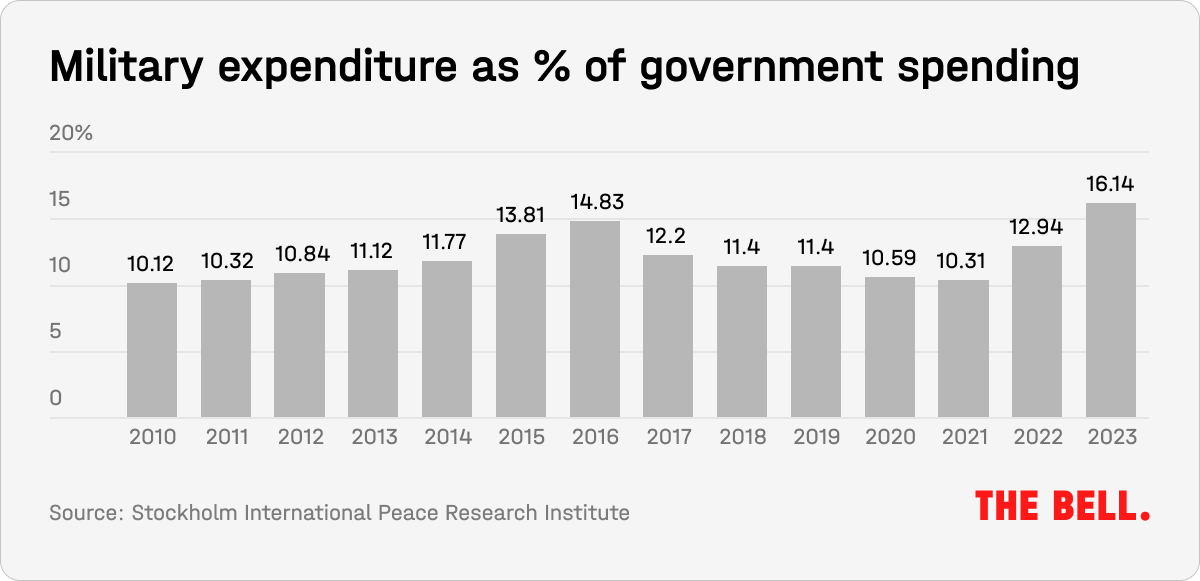

Last year’s budget also assumed there would be a reduction in military spending in 2025. Expenditure on “national defense” was supposed to drop a third in two years: from 10.3 trillion rubles this year to 8.4 trillion rubles in 2025, and then fall to 7.36 trillion rubles in 2026. Expenditure on “national security and law enforcement” was supposed to remain at 3.2 trillion rubles a year for the entire three-year period.

Even if Russia sticks to last year’s plans, expenditure on the army and security services will account for about a third of total spending. However, this is extremely unlikely to happen. It’s far more likely that the military will require more money. We have identified five reasons why we think Russia’s defense spending has a long way yet to rise:

1. The war continues

The war in Ukraine shows no sign of ending. Kyiv is currently taking delivery of $61 billion worth of U.S. military aid signed off by Congress in April, and Europe is still approving weapons shipments. Neither analysts nor policymakers anticipate a swift end to the fighting. If Putin wants Russian military success, this will require funding.

In one example of the costs of war, military salaries are rising rapidly. The Defense Ministry recruits about 30,000 soldiers a month, and their salaries are skyrocketing. At the start of the war they were on about 200,000 rubles a month, whereas now they can get up to 400,000 rubles a month. In addition, regional authorities are hiking the one-off bonus payments they make to new recruits. In St. Petersburg, the authorities are currently offering a 1.3 million ruble sign-on bonus. “The Ministry’s spending on salaries for servicemen, which was estimated at 1.5 trillion rubles… is now likely to be close to 2 trillion,” an official told The Bell.

2. Defense spending drives growth

The Kremlin has doubled-down on using the defense sector to drive Russian economic growth. For example, between January and April, manufacturing grew 5.2%. A significant part of that growth stems from defense and related sectors, including finished metal products, computers and optics, and vehicles from aircraft to ships and trucks.

For defense sector spending to be an effective driver of growth, there needs to be demand. Obviously, a drawn-out war in Ukraine provides this demand. Even after the war finishes, though, Russia will need to continue spending in order to replenish its stockpiles.

This suggests that military spending will remain high well beyond 2025. At some point, domestic demand will dry up. One way to compensate for this could have been export, but this is unlikely to be an option for Russia. As their output increases, Russian enterprises will need to replace equipment: Russia is already scouring China for second-hand machines. The parts needed for hi-tech military manufacturing are also scarce due to sanctions: chips, semiconductors and circuit boards are a problem. As a result, given a choice between exporting items or producing them for use by its own military, Russia countries will prioritize domestic needs.

3. Inflation and a tight labor market

Rising spending will also be driven by inflation, and high labor costs. Both high interest rates (currently at 16%) and reduced imports due to Western sanctions will push inflation higher. And there’s no sign of a slowdown in the growth of credit, or consumer demand, which means inflation could remain at present levels or rise even further. Between January and May, state spending was up 18%. Salaries in March increased 21.6% year-on-year in nominal terms, and 12.9% in real terms. Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov estimated in February that, in the defense sector, some salaries were up as much as 60%. A sales manager at a defense ministry contractor can earn up to 1.6 million rubles a month, according to a vacancy on Headhunter, Russia’s leading online recruitment site.

Unemployment is currently at a record low of 2.6%, with defense enterprises leading the way in hiring, and turners, machine operators and mechanics able to boost their pay by as much as 70,000 rubles a month if they switch to the defense sector. In addition, the defense sector promises staff additional benefits: increased overtime, bonuses for working with classified information, preferential loans, healthcare packages and vacations. Of course, the mobilization of 300,000 men in 2022 and 2023 negatively impacted the labor market. Moreover, the high cost of labor reduces the profitability of the military industry.

4. Inefficient command economy

Russia’s defense sector is a long way from operating along free market lines. This is due to several factors: a persistent Soviet management mentality, opaque pricing, and complex cross-subsidization within holdings (leading to chronic debt, and corruption). “Almost every factory has a boiler house, railroad tracks, a couple of sanatoriums and a bunch of real estate that has no value for production, storage or admin purposes. The company has to maintain all this, and it costs a huge amount,” said a source familiar with defense production.

State defense conglomerate Rostec estimates its profitability at 2.28%, but company head Sergei Chemezov has complained it should be as high as 10%. Without direct funding for R&D from the Defense Ministry, he said last month, factories are “on the brink of survival.” However, Chemezov also admitted that companies have little incentive to increase productivity, or reduce production costs.

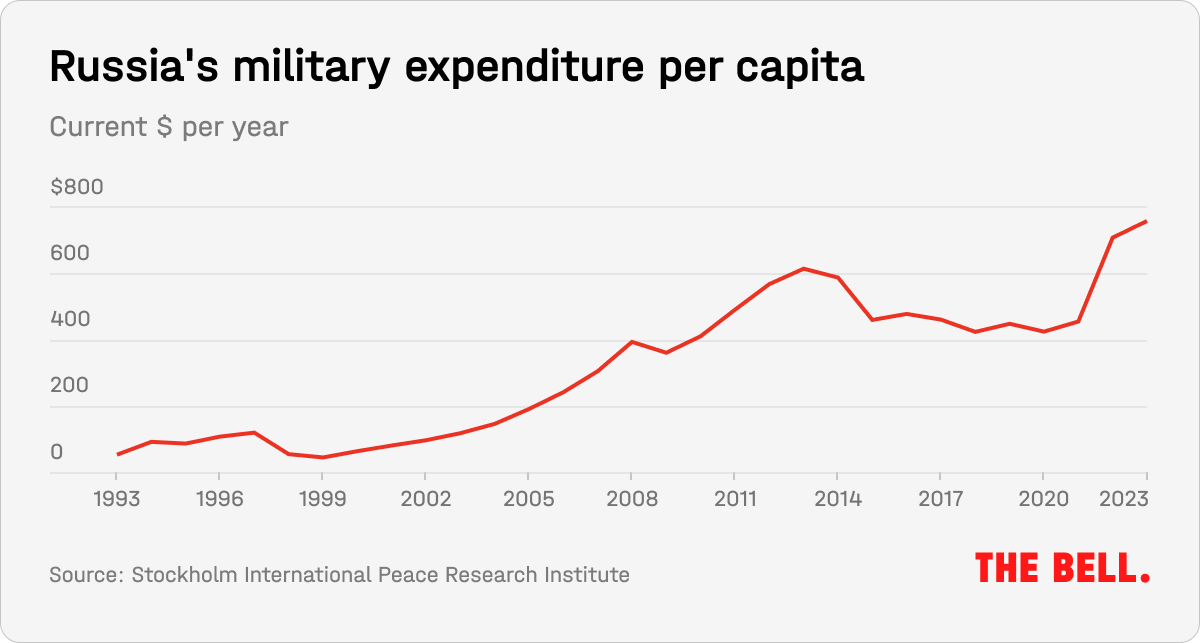

5. Rise in global military spending

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, global military spending was up 6.8% last year to a record $2.4 trillion. Russia’s military spending was above average – growing 24% to $109 billion. The total military spending of NATO countries in the same year was $1.3 trillion — 55% of the world total. Of NATO’s 32 members, including newcomers Finland and Sweden, 23 countries met the requirement to spend at least 2% on defense, according to the alliance. That’s the highest number of NATO states to meet that requirement since it was introduced in 2014. Putin likely believes this shows his enemies are arming, and that means it is unlikely that he will reduce his own military spending.

Why the world should care

Under the slogan of “all for the front, all for victory” the state is flooding the inefficient defense sector with cash, driving itself into the trap of increased military spending. This has interesting consequences. The mostly-market nature of the Russian economy means a bloated defense sector causes “Dutch disease” – i.e. it gobbles up all the available labor and capital, to the detriment of other sectors. The lack of effective management and built-in inefficiencies compound the issue, much like what happened in the late Soviet Union.

And we even know how some of this increased spending will be financed: this week, the State Duma passed a tax reform bill on first reading. More than 1.6 trillion rubles will be generated when corporate income tax goes up by 5 percentage points. It’s likely that this money will go directly to the defense sector.

Russia seeks to weaken ruble as imports fall

Russia relaxed Friday a requirement obliging leading exporters to sell foreign currency earnings. The order was first imposed in December 2023 as the ruble fell.

- The decision was made “taking into account the stabilization of the exchange rate” and “achievement of a sufficient level of foreign exchange liquidity,” according to a government statement. The Central Bank had always opposed compulsory sales, but in April, when the order was last extended, it failed to convince Andrei Belousov (deputy prime minister at the time), who regarded the sell requirement as a vital means of stabilizing the currency.

- This comes after the U.S. imposed sanctions on the Moscow Exchange earlier this month, and the Exchange was obliged to end trading of U.S. dollars and euros. This week, the ruble has strengthened, gaining 5% against the U.S. dollar and almost 7% against the yuan. Admittedly, it pared some of these gains starting Thursday.

- According to analysts, one reason for the rebound is sanctions. Part of the external balance of payment, unconnected to foreign trade, was closed due to an outflow of rubles. Now that process is complicated by difficulties withdrawing rubles and obtaining U.S. dollars for them. This is apparently a temporary problem.

- Another is problems with trade. The threat of secondary U.S. sanctions has frozen payments for Chinese imports, which were down at least 10% year-on-year in the winter. Russian state media reported that after Putin’s visit to China earlier this year, many small, regional Chinese banks started to work with Russian clients. However, this means higher commissions, which also hamper imports – and the U.S. is also trying to threaten smaller banks. This payment problem is clearly not yet fixed.

- In addition, a paradox has emerged: relative to the U.S. dollar, the yuan is cheaper in Russia than anywhere else in the world. Apparently this is due to the yuan’s novelty factor as a means of saving, and there is an excess supply of Chinese currency. However, as with any market imbalance, this will soon cease to be profitable.

Why the world should care

Most of the factors behind the ruble rebound seem to be temporary and, in many cases, resemble a scaled-down version of the period of ruble strengthening in 2022 after the full-scale invasion led to disruption to imports and capital outflow routes.

Figures of the week

In the week up to June 17, weekly inflation in Russia increased to 0.17% . Annual inflation ran at 8.46%. The latest Central Bank report on consumer price dynamics noted that the seasonally adjusted monthly rate of price increases was 10.6% and the current rate in May was “significantly greater” than the previous year. The bank believes that high domestic demand is the key inflationary factor.

Banks are prematurely curtailing lending under the preferential mortgage program, which will cease to operate on July 1 (for more on why that’s important, see here). From June 21, state-owned Sber will stop accepting applications for discounted mortgages at 8% and will stop issuing IT mortgages. Bringing an end to the current preferential mortgage set-up is a long-standing aspiration of the Finance Ministry and the Central Bank.

The Central Bank increased its prediction for the growth of household funds held in bank accounts this year to between 14% and 19%. Previously, the prognosis was between 8% and 13%. Expectations for businesses remain the same. By the end of 2024, lending is expected to increase sharply in all sectors: the issuance of consumer loans will be up as much as 12%, corporate loans by up to 13% and mortgages up to 12%.

The Central Bank increased its forecast for the net profits of Russia’s banking sector in 2024: now the expectation is between 3.1 trillion rubles and 3.6 trillion rubles. If this happens, banks could match the record profits they enjoyed in 2023 (3.3 trillion rubles). In 2025, the regulator expects another successful year (up to 3.1 trillion rubles of profits).

Further reading

How the Latest Sanctions Will Impact Russia—and the World

Putin and Kim’s New Friendship Shouldn’t Be a Surprise

Late-stage Putinism: The war in Ukraine and Russia’s shifting ideology