A ‘competitive’ tax rate?

Finance Minister Anton Siluanov keeps saying that even after income tax rates go up, Russia’s tax regime will remain “competitive and comfortable.” It is true that Russia’s headline rate of personal income tax rate was, and will remain, low compared with other countries. But those who paid close attention always knew that the real tax rate was never 13%. After accounting for payroll taxes and insurance premiums paid by employers, the overall tax on labor can be almost three times that level. How does this figure compare with other countries, and how will it change after the planned tax increases?

13% or 43%?

Last week, the finance ministry officially unveiled its plans for a major “reform” of Russia’s tax system. One of the main changes will be the introduction of higher bands of income tax that will see Russians earning more than 2.4 million rubles a year ($27,000) paying more to the state. Under the proposals, Russia will move from having just two bands of income tax (13% and 15%), to five: 13, 15, 18, 20, and 22%. The highest bracket will apply only to those with annual incomes of more than 50 million rubles ($560,000).

But the headline rate of income tax alone does not reflect the full tax burden on workers. A common refrain in Russia is that income tax is not 13%, but 43%. That’s because in addition to the 13% rate paid by employees, firms also have to pay up to 30% of stated salaries in compulsory insurance premiums. Therefore the cost to businesses of hiring staff is actually a lot higher (though not quite 43%, as we explain below).

Technically, the level of those employer obligations depends on the headline salary rate. The lower the salary the higher the premiums. For the vast majority of employees who have salaries with a so-called “tax base” of below 2.225 million rubles per year ($25,000), the rate is set at 30%. Above that, it drops to 15%.

Discussion of these details, of course, has been absent from the government’s presentation of its “tax reforms” as fair and just. Finance Minister Siluanov has stressed that despite the new changes, Russia’s income tax will remain competitive compared with other countries. That message extends into the government’s official handbook on the changes. A simple increase in the headline rate from 13% to 15% (not considering the bands that apply only to Russia’s ultra-high earners) would not really change much for Russia’s global standing. But The Bell wanted to investigate whether Russian taxes should still be seen as competitive when those “hidden payments” are factored in.

The tax wedge

Looking at what economists call the “tax wedge” — the difference between how much an employer pays to hire somebody in wages and payroll taxes, and how much ends up in the worker’s pocket after all the necessary deductions — is a better way of assessing how competitive a country’s tax system is than headline interest rate payments

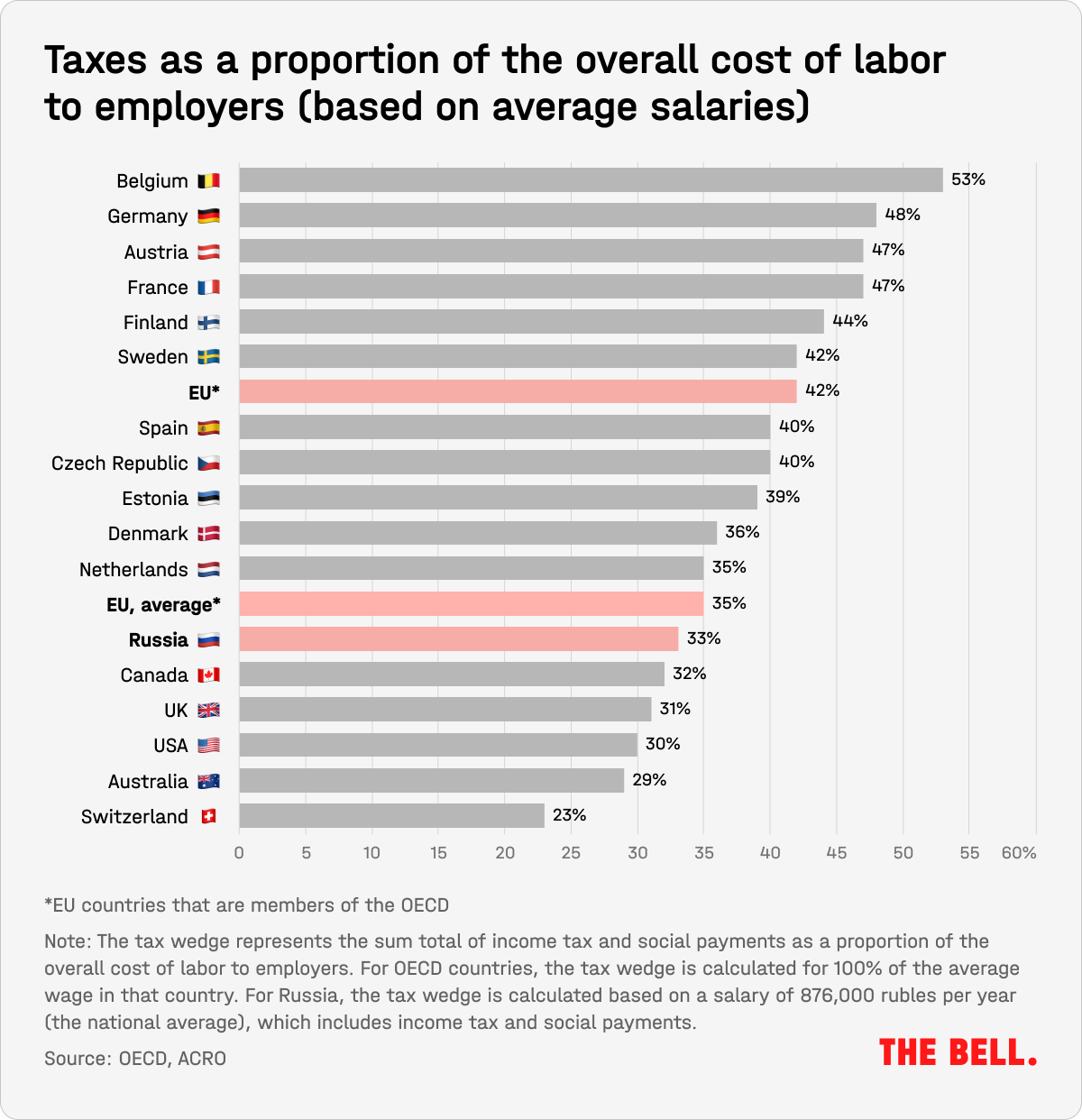

Taking a hypothetical Russian example. An employee’s stated gross salary is 100,000 rubles a month. After the 13% income tax rate, they take home 87,000 rubles. The employer also pays 30% of their gross salary (30,000 rubles) in insurance contributions. That means the employer has spent a total of 130,000 rubles, while the worker has received 87,000 rubles. So of the total outlay, some 43,000 rubles or 33%, has gone to the authorities. It’s not quite the 43% rate that Russians regularly cite, but it’s still a lot higher than the much-vaunted 13% rate the government talks up.

The OECD publishes “tax wedge” rates for major economies on an annual basis. The calculations can get a bit tricky once all kinds of different allowances and salary thresholds are taken into account, so the organization publishescomparative breakdowns based on representative employees earning different salaries, up to 167% of the national average.

That figure allows a good comparison of the tax wedge for the vast majority of workers,s save for the very highest earners. “Unlike Russia, [OECD countries] have less differentiation in income among the population and the lower classes are much better protected. Therefore, for them, 167% is quite a high salary,” said economist Alexandra Osmolovskaya-Suslina, who co-wrote a scientific paper about progressive labor taxation in Russia.

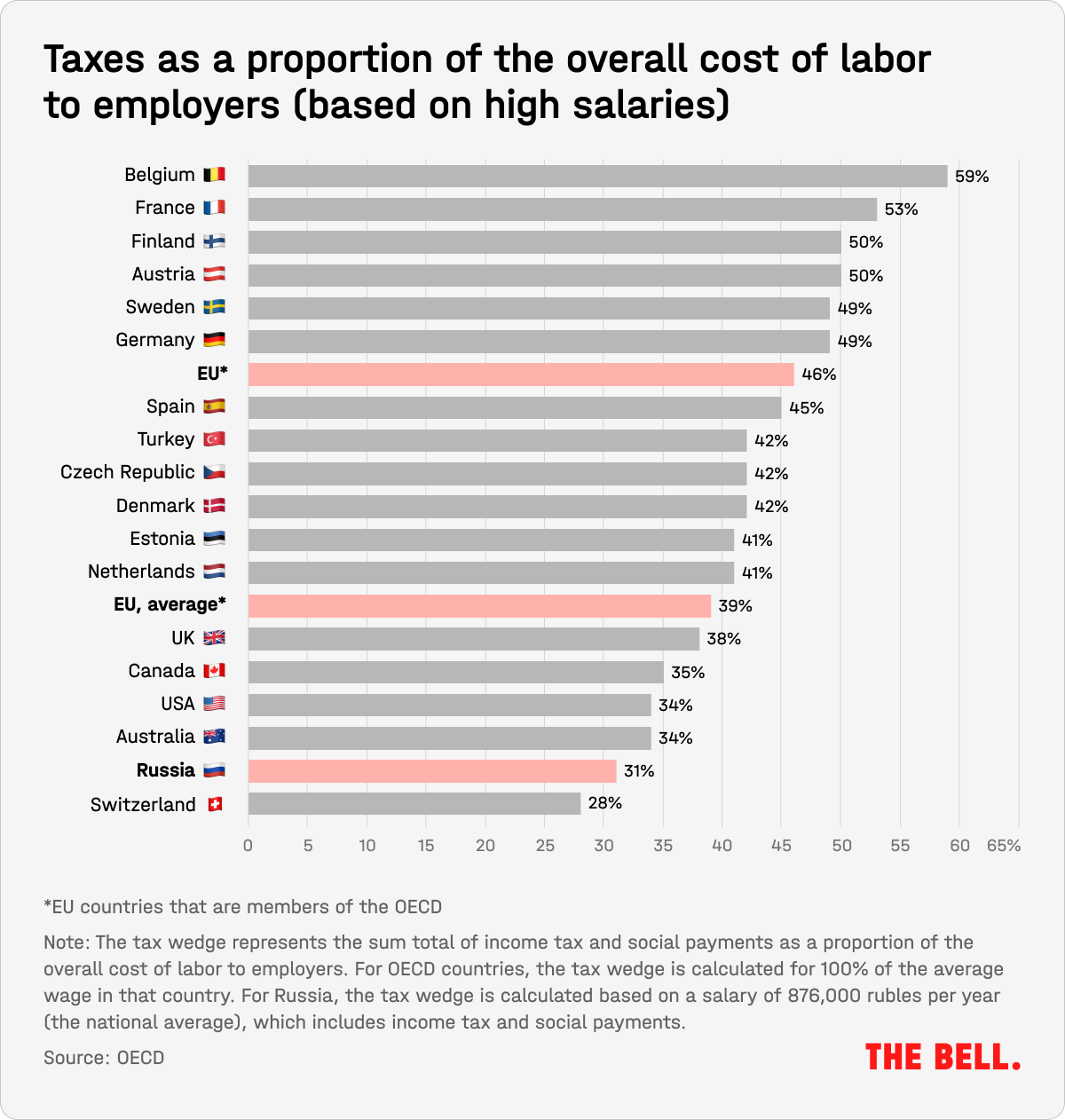

The biggest average tax wedges among OECD countries — taking the example of an unmarried high-income individual without children (i.e. with no allowances) — are in Belgium and France. Somebody earning two-thirds more than the national average salary would see a tax wedge of 59% and 53% respectively. The lowest levels are in New Zealand (25.6%), South Korea (23.1%) and Chile (8.4%). The OECD average in 2023 was 39%.

For Russia, the latest calculations by the Moscow-based ACRA ratings agency were made at the end of April, before the proposed tax changes were announced. They assumed the Finance Ministry would introduce a new seven-threshold income tax scale and set the 15% rate to kick in at annual earnings of 3 million rubles (the actual proposals set this a little lower, at 2.4 million rubles). But even with the updated parameters, the calculations are almost the same. They found the tax wedge on a salary of 2.4 million rubles a year was around 31%.

The lower the salary the higher the wedge. For instance, for those earning 10 million rubles a year, it equates to around 29%, while on the average Russian salary of 876,000 rubles ($9,800), the tax wedge is 33%. That rate is still lower than every OECD country except Switzerland.

“These examples show that it is important to discuss issues of tax progression and the tax burden in a broader context than just the personal income tax scale. Moreover, income inequality is affected by taxes that do not formally differentiate rates according to income, such as sales and property taxes, as well as systems of social support and tax deductions,” the authors of the Russian report said.