A Private Army for the President: The Tale of Evgeny Prigozhin’s Most Delicate Mission

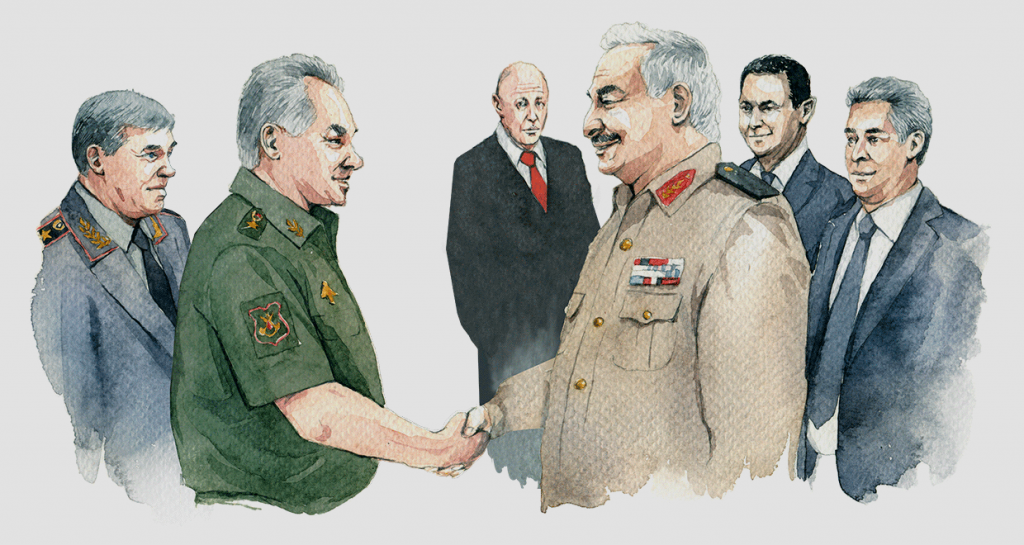

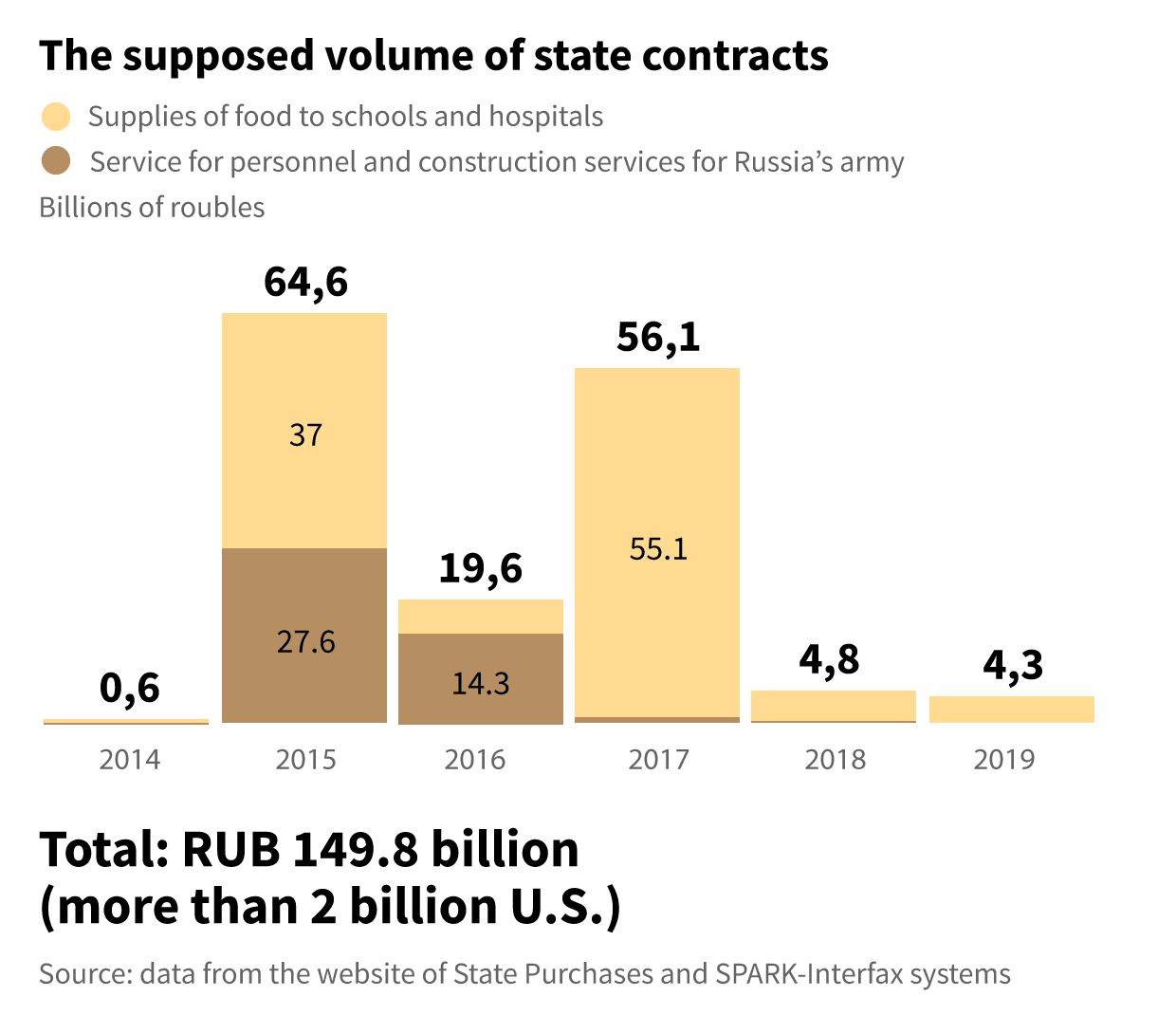

The name Evgeny Prigozhin has become synonymous with Russia’s informal presence in conflict zones where Russia has interests, from Syria to West Africa to Venezuela. The Bell has learned that “Putin’s chef” might have received this risky mission — to participate in the creation of a private army — in due course from the highest military leadership, but the idea itself dates back to the 2010 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. Prigozhin himself aggressively denies his participation in the creation of a private military company, and says that the size of his business has been largely overstated.

Highlights

- The Russian General Staff came up with the idea to form a private military company

- The founder of one the world’s most successful private military companies Executive Outcomes, was a consultant

- Prigozhin for the first time gave detailed commentary on his links to Wagner Group for The Bell

I. The military came up with the idea of a private army

“Everything began when our generals met Eeben Barlow,” one source with good contacts in the Ministry of Defense told The Bell. “He gave a short speech about the use of mercenaries right there at the St. Petersburg forum.”

In the official program of the St. Petersburg economic forum in June 2010, Barlow’s name is listed as a participant in one short session about how the military can cooperate with the private sector and whether it’s possible to “privatize” the army. But the main reason for his visit was a closed presentation for a small delegation of the General Staff.

Eeben Barlow, founder of the South African private military company, Executive Outcomes. Photo: Wikipedia

“A private army doesn’t have an ideology, a motherland, or a flag. It has just compensation,” American journalist Robert Patton describes the ideology of private military companies in his book, Licensed to Kill. Barlow is described in the book.

Barlow is a former lieutenant general of the South African security forces and the founder of a military company which became the model for private military contractors like Blackwater. At the end of the 1980s, when the apartheid regime started falling apart, and the country’s military was on the verge of dismantling, Barlow founded the company, Executive Outcomes, which for the next 15 years made the leaders in Africa nervous.

Films were made about this African private military company and military searches in Angola and Sierra Leone, suppression of government coups, several civil wars, its headquarters in London and provision of expensive services to protect valuable shipments and western companies’ assets. Influential television journalists visited the company’s military bases, and Barlow himself wrote several books about his company.

But it is unlikely that even the best-read visitors to the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June 2010 would have recognized a legend in the form of a rather weak looking European of about 50.

Barlow himself told The Bell that he remembers his speech in St. Petersburg very well:

“Already then I said that private military companies from the west and the east will overrun Africa. In both places there are people who are looking for power, influence and control over resources. That’s exactly what happened.”

Barlow didn’t discuss the details of his visit, explaining that he hates journalists and he stopped answering our messages.

During the forum in St. Petersburg, Barlow told the military about the model for the creation of a private military company, and even offered options for adapting such a company to Russian conditions. The main question discussed afterwards was whether such a structure would be legal, but some of the siloviki were categorically against the idea because of clear difficulties in controlling the flow of weapons.

This was less than four years before Crimea was annexed, and there was no discussion of Russia’s participation in large military campaigns abroad. The idea was to use “illegals” for special tasks in order to minimize publicity and the number of problems in the event of a failure.

The Ministry of Defense remembered well the lesson of 2004, when three soldiers were arrested in Qatar and suspected of liquidating the accused terrorist, Zelimkhan Yandarbiev. It was only possible to secure their return to Russia after Vladimir Putin personally intervened. The concept’s main idea, according to sources close to the Ministry of Defense, was that mercenaries wouldn’t have to be dragged into action — they take risks in exchange for substantial compensation.

The reshuffle of Vladimir Putin with Dmitry Medvedev, the scandal following the resignation of Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, the retirement of the head of the General Staff, Nikolai Makarov — all of this put the idea of a private military company on hold for a few years. But it wasn’t forgotten.

Army General Valery Gerasimov, who took over from Makarov in 2012, supported the idea. As he had direct access to the president, it is likely that he sought the president’s approval, sources told The Bell. Vladimir Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, refused to comment for this article.

II. Prigozhin is asked to organize a private military company

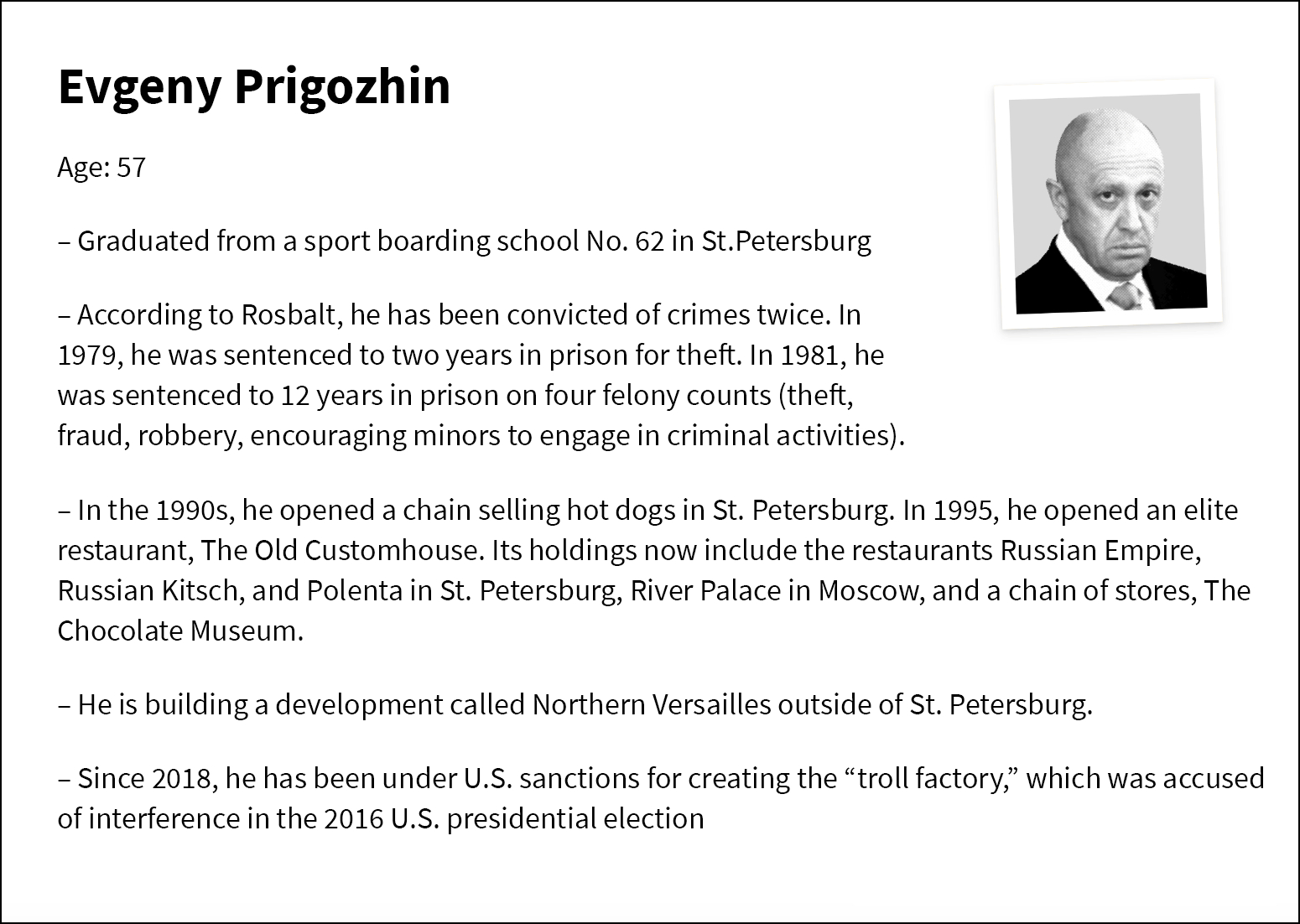

The idea to make St. Petersburg restaurateur Evgeny Prigozhin responsible for financing and operational issues originated in the General Staff, sources close to the Ministry of Defense told The Bell. After 2010, he began to build his business supplying food for state orders. Beginning with school lunches, Prigozhin grabbed the market, which he himself estimated to be worth a trillion roubles (34 billion U.S.) in 2011: “We have plans — an army. That’s more than half a million people. The police – two million…” the businessman said in an interview published in 2011 on the St. Petersburg portal Gorod 812.

By the end of 2012, according to Forbes, the value of contracts directly or indirectly related to Prigozhin surpassed 90 billion roubles.

For this article, Prigozhin, possibly for the first time, gave detailed commentary on the topic of private military companies and on their place in the market for state contracts. Through a representative, Prigozhin said that he doesn’t have companies that supply or offer services to the army “with the exception of rare events in the context of catering services,” and that he himself has no ties to the Wagner private military company.

Prigozhin’s candidacy didn’t come about by accident: he is a “person of action”, “he gets what he wants”, sources in the Ministry of Defense told The Bell. But most important — Prigozhin is personally acquainted with Putin, and Putin trusts him, one source emphasized. The key factor in selecting a candidate might have been that unlike Gennady Timchenko or Arkady Rotenberg, old friends of Vladimir Putin who were already successful businessmen, Prigozhin wasn’t part of the inner circle and had remained in the shadows for much longer.

If one believes the businessman’s own story, Prigozhin met Putin more than 20 years ago. “We met when he came with Japanese Prime Minister Mori, and then with Bush,” the restaurateur said in 2011. It’s most likely that he was speaking of Yoshiro Mori’s visit to St. Petersburg in April 2000, when Putin was still acting president. George Bush visited St. Petersburg during his visit to Russia in 2002. The city planned carefully for his visit, and Prigozhin would have played a direct role in the preparations.

For George and Laura Bush’s stroll along the canals, a double-decker ship with Evgeny Prigozhin’s floating restaurant, New Island, was selected and decorated in the style of an American saloon.

The head of the Ministry of Defense, Sergey Ivanov, was at the dinner, along with the deputy head of the presidential administration, Sergey Prikhodko. From the U.S. side, Secretary of State Colin Powell and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice were there. Putin was likely pleased with the event. In the fall of 2003, Putin celebrated his birthday in the same restaurant.

By 2005, the restaurateur, in his own words, had Russia’s largest catering company — “we did all the G8s, the summits”. In 2004, his company catered the banquet in honor of Silvio Berlusconi, this time not in St. Petersburg but in Novo-Ogarevo.

This was revealed from chats between employees of Prigozhin’s catering company, Concord, which were later published by hackers from “Anonymous International”. In the chat, one of Prigozhin’s deputies recalled what was discussed between the heads of state over dinner.

«Prigozhin hears a lot at various meetings, and at first glance he appears so ordinary, but he remembers everything, and tries to find a use for that information,” a senior government official told The Bell.

If one believes the restaurateur himself, Prigozhin could have gone right to the president through Alexander Beglov, a former St.Petersburg city administration official who knew Putin since the early 1990s in St. Petersburg (in 2018, Beglov was appointed acting governor of the city).

Beglov worked for a long time in the Kremlin, was deputy head of the Northwestern Federal District, and at the end of last year replaced Georgy Poltavchenko as acting governor of St. Petersburg.

Prigozhin might have had some help in getting the first contracts for his private companies to supply food to the army from Leonid Teif, formerly deputy general director of Voentorg (the supplier of consumer goods for the army, owned by the Ministry of Defense) Leonid Teif, according to a 2012 Novaya Gazeta report. According to the newspaper, it was Teif who managed the handover to Prigozhin of Voentorg assets, which were involved in supplying produce and cleaning supplies to the army.

Recently in the U.S., where Teif now resides, he was accused of organizing schemes for Ministry of Defense contracts, for which bribes in the amount of roughly $150 million were paid. (In addition to money laundering, Teif (insert hyperlink) is accused of bribing U.S. officials, planning murders, illegal storage of weapons, and also of deceiving immigration authorities.)

Before he got involved in the mercenary military he’s allegedly affiliated with, Prigozhin’s companies started winning government contracts to provide cleaning, catering and heating services to military bases, and to perform construction works at military towns. Moscow schools and hospitals provided another large source of state orders for his companies, as did the presidential administration.

Some of the money received from the state was spent as it was intended, but the rest was used to organize private military companies, sources close to the Ministry of Defense told The Bell.

It is impossible to precisely estimate the size of the orders because most of the companies which the media earlier tied to Prigozhin were indirectly tied to the businessman’s circle, to the activities of his Concord group, and were related either by address, or telephone number, or by having one or more of the same directors.

Prigozhin himself said that The Bell’s calculations regarding Concord are not accurate (but we took into account not just Concord’s orders but those of other companies which are believed to be tied to the businessman).

III. The private military company’s biggest success and failure

The private military company (PMC) began to be formed in 2013, explained one person who worked for many years on a variety of tasks abroad, including military. He himself was invited to an “interview” by the head of Prigozhin’s security service, Evgeny Gulyaev, a former operative of the St. Petersburg police. “I arrived at the first meeting, and I immediately got the impression that Prigozhin doesn’t like this whole idea with the PMC, and I liked him even less,” the source told The Bell. At the beginning, Prigozhin really wasn’t happy about the project, as it was dangerous and the benefit wasn’t clear, another source close to the Ministry of Defense told The Bell. “But these were orders you couldn’t refuse,” he added elegantly.

Fontanka was the first to write about the “Wagner group” in the fall of 2015: the publication has had the most complete coverage of the private military group’s activities since then. Possible ties between Prigozhin and the private military company were then investigated by other media outlets — for example, RBC, WSJ, BBC Russian, and Fontanka. The Bell’s sources close to the Ministry of Defense also confirm these ties.

But Prigozhin himself denies not only his involvement but the existence of a private military company in his answers to The Bell’s questions.

“In the Russian Federation, there is not the concept of a private military company (PMC). The fact that my name is used in connection with a PMC is the result of information which was initially passed onto society by Ukraine’s security services (…),” Prigozhin said. “Journalists often write about the presence of a PMC in other countries. Tell your readers how to differentiate a PMC guy on the street from a “Wagner” one?”

In February-March 2014, mercenaries were spotted in Crimea, and later in the southeast of Ukraine. The Ministry of Defense then called such information “an info dump”. The PMC’s role in the events of the “Crimean spring” was clearly limited, two sources close to the Ministry of Defense told The Bell: the official number of military personnel transferred to Crimea was clearly enough to provide for the population’s security and to defend against resistance from Ukrainian troops. The PMC could test its strength in the southeast of Ukraine, but there its role was far from a leading one: despite the high level of preparedness, the “retirees” demanded constant training so that commanders and soldiers could get to know each other.

In order to “rally the team” in approximately mid-2015, a place was selected not far from a GRU base in the south of Russia. The military part of the GRU was served primarily by companies tied to Prigozhin, RBK reported. They could equip and house mercenaries, the publication suggested. “In the Ministry of Defense, with which I have no ties, I can’t hold talks about financing or equipping a PMC which doesn’t exist,” Prigozhin told The Bell.

Reserve colonel Dmitri Utkin could have been responsible for the PMC’s military preparation and directly in combat, Fontanka wrote. The “Wagner” name, which the media began to refer to the PMC as, Utkin might have gotten for his Germanophobia; even the area between the tents in the training camp was called “Die Straße”.

Already in August 2015, “PMC Wagner” had hired fighters and was preparing them for their first tour in the Middle East, a mission to Syria.

The Ministry of Defense insisted that Russian troops did not participate in operations on the ground, until group commanding general Alexander Dvornikov said in March 2016 that “specific tasks” on the territory of the republic are being decided by “divisions of our troops for special operations”.

During offensive operations by the Syrian army with support from Russian aircraft, mercenaries were often on the front lines. “First the Wagner guys work, then Russian ground groups come, then finally the Arabs and the cameras,” one of the participants told the publication. The peak of all operations was the seizure of Palmyra in 2016, in which Wagner fighters played a decisive role. In March, the city was returned to Syrian government control, and two months later, the Mariinsky symphony orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev performed a concert in the ancient amphitheatre.

It was a triumph: at the end of the year, Utkin and several PMC fighters were invited to the Kremlin. The head of the PMC was featured in a report on Channel One in a ceremony in honor of heroes of the fatherland. On December 9, 2016, a photo was published online which in all likelihood Vladimir Putin posed for with Utkin and other PMC commanders.

Photo: War News Today/VK.com

But already soon after the first victories came dark clouds — in February 2017, the private army suffered its first major losses, and Prigozhin felt the anger of the military command, two sources close to the Ministry of Defense explained. The reason was the PMC’s battle in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor, in which, according to various unconfirmed reports, from several dozen to more than one hundred PMC fighters died (Reuters has reported that at least 40 Russian military and PMC personnel lost their lives in 2017).

Kommersant, comparing the versions put forward by the Pentagon and Ministry of Defense, described the situation this way: on the evening of February 7, around 250 (according to other sources, 600) pro-Syrian government fighters, supported by PMC Wagner mercenaries, moved towards the region of the former oil refinery, Al Isba.

The goal of the offensive was the attempt by local “major businessmen”, supported by Bashar al-Assad, to grab the oil and gas fields which were under control by Kurdish forces, allied with the U.S., a Russian military source told the publication. American troops responded. The column came under artillery fire, which lasted more than three hours. Later the Pentagon announced that after discovering the column, U.S. troops warned Russia’s Ministry of Defense, which said that there were no Russian troops in that area, after which the Americans launched a massive attack.

The PMC fulfilled the order of a Syrian businessman, a source from another private company confirmed to The Bell. Not long before these events the company Evro Polis, which media reports have also tied to Prigozhin, concluded an oil deal with the government of Bashar al-Assad. The Bell learned the company has signed a binding agreement to participate in Syria’s oil and gas projects — its specific conditions are not known, but it is believed that the company would free oil and gas fields and oil and gas refining assets from enemies of the Syrian government. In return, the company could claim one quarter of the oil and gas produced on these territories.

The attack, which was reported around the globe, was not sanctioned by the Russian commanding officer in Syria, two sources close to the Ministry of Defense said. The military was “simply dumbfounded” by the turn of events, one of them added. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs had to admit, a few days later, that Russian citizens took part in the battle, but that they were not part of Russia’s military, and that five were killed, and dozens of injured were given medical aid and flown back to Russia for treatment.

“There are Russian citizens in Syria who went there on their own volition and with various goals. It is not the job of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to evaluate the eligibility and legality of such decisions,” the department said in its statement.

This episode was one of the most painful for the PMC and for Prigozhin personally, one source close to the Ministry of Defense told The Bell. Without divulging details, it was made clear by two members of the military that afterwards it was hard work to convince the presidential administration that this “misfire” was a one-time event, and that “corrective work” will be carried out on those responsible.

IV. Expanding PMC’s geographic reach — from West Africa to Venezuela

From the moment of the battle at Deir ez-Zore, there was no further information about PMC’s participation in active battles, but the company’s employees were spotted in almost a dozen other countries, mostly in Africa. This surprisingly coincided with Russia’s active diplomatic posturing with leaders of African states.

In just the past year and a half, Russia and its state companies signed agreements on military and economic cooperation with Guinea, Niger, Chad, Nigeria, CAR, Libya, and others. And Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev personally met with the leaders of Sudan (its president Omar Bashir promised to give Moscow “the key to Africa”), Gabon, CAR, and Libya’s commanding general, Khalif Khaftar.

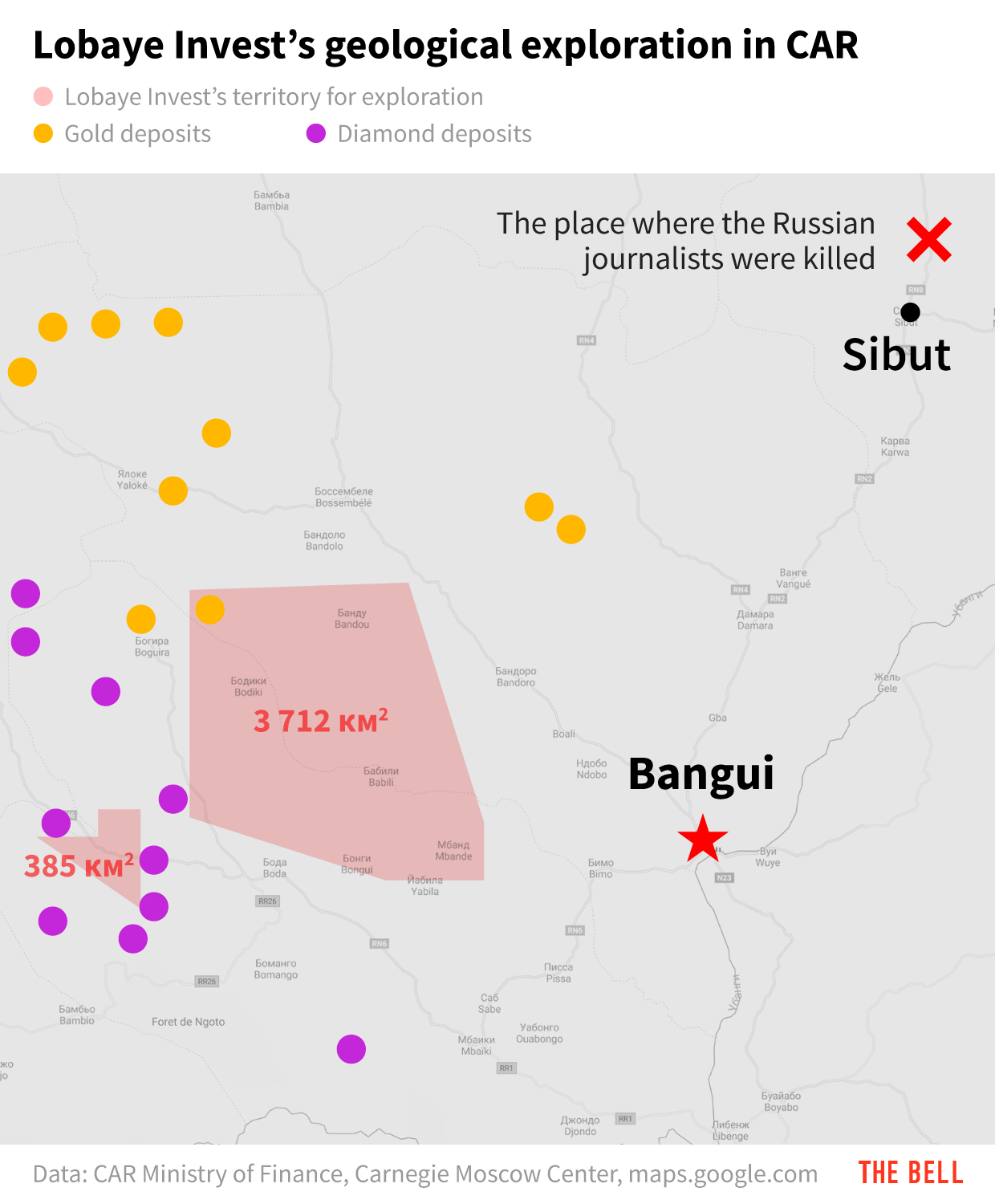

Since the end of 2017, PMC Wager mercenaries or Russian political-technical experts began to appear in Africa, according to sources, data and local media reports. The Bell reported that a deal was made with the leaders of Sudan similar to the deal made in Syria: a concession agreement for gold mining was given in exchange for training the local army’s hired soldiers. One of the next hot points became CAR. Officially, according to the agreement with the UN, 5 military personnel and 170 Russian civilian instructors have been working in the country since January 2018. Even the UN report did not specify who these instructors are, what status they have, and what they are doing. However, The Bell was able to find documents showing that the company, Lobaye Invest, believed to be tied to Prigozhin, received two licenses in CAR to explore and produce gold, diamond and other deposits of precious metals which might be found on the territory of 4,000 square kilometers. Three journalists who planned to investigate what was happening in CAR died there under unclear circumstances, Orkhan Dzhemal, Kirill Radchenko and Alexander Rastorguev.

At the end of 2018, Russia was suspected of sending troops to Libya, and then Prigozhin was spotted in a video with the head of the Libyan army. It turns out that he personally took part in talks in Moscow which Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu held with field marshal Khaftar. “The famous Russian restaurateur Evgeny Prigozhin […] organized an official lunch and took part in the discussions of the visit’s cultural program for the Libyan delegation,” a military-diplomatic source later told TASS.

Photo: screenshot of a video from the information bureau of the command of the Libyan military

The “dangerous mix” of mercenaries and political-technical experts offering African countries defense services, training and consulting ahead of elections, Bloomberg wrote in its November investigation. According to its data, PMCs from Russia are working or are about to begin working in 10 countries with whom Russia’s military has already established relation. The agency named the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Libya, Madagascar, Angola, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and the Central African Republic. In March, Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov made an official tour of five African countries.

Political operatives from Russian have already consulted Zimbabwe’s current president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, after the military coup in the country last year. They have also prepared the current head of Congo, Joseph Kabila, ahead of elections, as well as several candidates in Madagascar, the agency reported with a link to its sources. A former employee of the St. Petersburg central police department, Valery Zakharov, is now an official security advisor to CAR president, Faustin Archange-Touadera.

At the end of last week, Reuters reported, with a link to its sources, that PMC Wagner mercenaries were in Venezuela. In the face of an attempted change of power, they were supposedly told to protect president Nikolas Maduro. Peskov denied this. “Fear has big eyes. No, of course not,” he said in response to a question “so are our 400 troops protecting Maduro in Venezuela or not?”.

Following the example of the legendary Executive Outcomes, PMC Wagner has the potential to become a multi-profile holding, providing its clients a wide range of services, from physical protection of leaders and security for various assets to direct military participation. It will likely be possible in a few years to measure if the company will be able to become a profitable enterprise.

But before it shows profit, the company has to offset its expenses. According to The Bell’s sources, since 2014, between 7,000 and 10,000 mercenaries may have worked for Wagner. At the beginning of the Syrian campaign, the private army, including compensation to those killed in action, cost a minimum of 5 billion roubles (nearly 100 million U.S.) annually, RBC estimates. Last year, expenses, according to The Bell’s calculations, on the basis of the estimated number of groups and estimated expenses, could have decreased to 2 billion roubles (32 million U.S.).

In response to The Bell’s question whether PMC Wagner is a commercial structure, focused on increasing profits, Prigozhin said that he would give a “philosophical answer” and suggested we learn to think logically:

“If PMC can exist somewhere abroad, then it can be assumed that it is engaged in security and military activities. It is most likely that this company is focused on turning a profit. However, projects related to the production of precious metals are carried out by mining and production companies. There is no place for PMC in the area of mining and production companies’ activities.”

Irina Malkova, Anton Baev

Anastasia Yakoreva contributed to this report; a journalist from another publication also contributed to this report upon The Bell’s request.

Translation by Tanja Maier, editing by John Temple, the managing director of the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley.