This newsletter is made with the support of the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley.

A proposal to nationalize company profits triggers a fight between the Kremlin and government

1. A proposal to nationalize company profits triggers an unusual fight between the Kremlin and government

Vladimir Putin at a meeting with businessmen, March 2017. Photo credit: TASS

What happened

An idea put forward by Vladimir Putin’s economic advisor to take almost $8 billion from the profits of big business to fund government spending has caused a rare public conflict between the Kremlin and government ministers. The outcome of this dispute might determine the nature of the economic program for Putin’s fourth term.

- We wrote about the controversial proposal by Putin’s economic advisor Andrey Belousov last week. In short, the idea is that — because Russian metals and chemicals producers have earned higher than usual profits due to rising commodity prices and a weaker rouble and they pay less tax than oil companies — it would be fair to ask them for about one-third of their 2017 EBITDA, or 500 billion rubles ($7.6 billion). This windfall will be used to help finance Putin’s so-called “May orders”: a plan to develop the Russian economy through 2024 with the help of massive government spending (about $380 billion). Putin reacted positively to Belousov’s proposal.

- Belousov, the author of the idea, is one of the least well known and, at the same time, most influential economic decision-makers in power. Putin, no matter how authoritarian his regime, traditionally trusts liberal economists to run the economy (other examples are Sberbank head German Gref and Alexey Kudrin, who served as finance minister for many years). Belousov is an exception to this rule. In the system built by Putin, he acts as a counterbalance to the “liberals in government”. A highly ranked Russian government official has described him as “a rigid statist” who believes Russia is surrounded by “a circle of enemies”. In 2014, Belousov was the only one of Putin’s economic advisors to support the annexation of Crimea. In the eternal debate about how to allocate revenue from oil and gas profits, Belousov always argues that money should be spent on infrastructure projects — and not set aside in rainy day funds.

- The letter written by Belousov found its way into the press last Thursday and drew sharp criticism from business and experts. Nor did it please officials responsible for the economy. However, after government meetings at the end of last week, company representatives grudgingly acquiesced (Russian). A proposal such as this with Putin’s approval is not usually discussed further. But, then something changed. On Thursday, five government ministers sent strong negative feedback on Belousov’s idea. According to The Bell’s sources close to the companies, the position of the officials changed after they realized that the controversial idea had no final confirmation from Putin.

Why the world should care

It is not surprising that Belousov’s proposal has drawn more public criticism from government officials than the far more painful decision to increase the pension age. Such a move to retroactively take profits from private companies would indicate a change in the rules of the game. In essence, it would be a step towards a Soviet-style planned economy. Before 2014, this would have been impossible, but in the context of a growing conflict with the West and increasing sanctions, such a scenario looks more and more plausible.

2. Russia does not fear a repeat of the country’s most serious ever financial crisis in 1998. However, economic isolation might change that

What happened

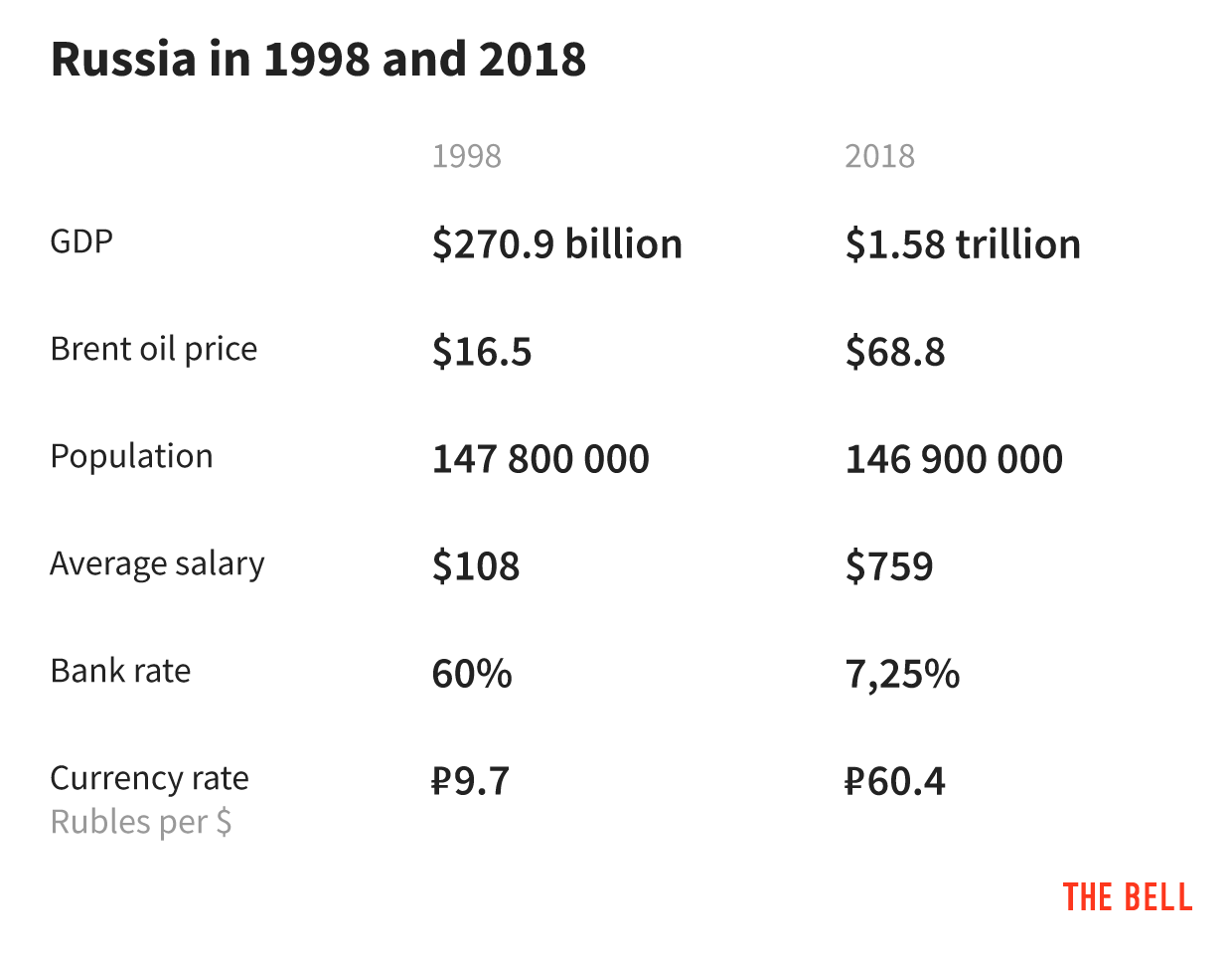

Today, Russia is looking back on the 1998 crisis — the most serious financial shock in the country’s modern history which contributed to the formation of Russia’s modern economy. The current problems in Russia don’t look anything like those which led the country to default on its debt 20 years ago. But Russia’s increasing international isolation and the state’s increasing role in the economy might push the government towards decisions which might bring the country closer to a similar crisis.

- The default on its debt and the three-fold devaluation of the rouble in 1998 were the first major crisis for Russia’s market economy. Then, the country’s citizens, government and new businesses had only just learned to live by the rules of the market economy. For all three groups the crisis was a serious blow. For the second time in a decade, citizens lost all of their savings which they deposited with banks. Businesses which were not involved in the export of natural resources either went bust or found themselves on the verge of bankruptcy. The government faced a huge crisis of legitimacy, the ultimate result of which was Vladimir Putin’s rise to power.

- The crisis was primarily caused by the Russian government’s inability at the time to meet its budget through tax collection, Sergey Dubinin reflected in his article in today’s Vedomosti newspaper. Dubinin was head of the Central Bank in 1998. Instead, the government printed money for several years and accepted hyperinflation, and when this practice had to come to an end, the country found itself totally dependent on external debt and speculative investors who bought Russian government bonds. As soon as they left the market, the entire market collapsed. The crisis was difficult, but not lengthy: already the next year, in 1999, the Russian economy grew by 6% and continued to grow continuously at a quick pace until 2008.

- It is commonly thought that these events played a decisive role in the formulation of the views of those government officials who are now responsible for the Russian economy. They fear high levels of external debt, any dependence on external credits and high inflation, and use all opportunities to grow reserves and (particularly in the last four years) are not afraid to devalue the national currency in order to increase export revenues. In many ways, this explains Russia’s present fairly strong macroeconomic indicators.

Why the world should care

Russia’s increasing international isolation, which pushes the economy to become more self-contained, might change the situation for the worse. Although Andrey Belousov’s proposal to nationalize the profits of private business hasn’t been pushed through, we see that the Russian state is having a harder time finding money to finance government spending. If all other sources will be used up, and in the context of sanctions, the government might have no other choice but to print money — and then 1998 in Russia really might happen again.

3. Banks face new crisis as borrowing outpaces income growth

What happened

While the falling ruble and U.S. sanctions are making headlines, there is a new credit bubble in Russia. The amount of debt held by Russians has grown twice as fast in 2018 as 2017, and five times faster than real income levels. This increase might spark a crisis for Russian banks. Moreover, this week it became clear that, according to new financial reporting rules, the share of bad debt held by Russian banks is twice as high as official statistics suggest.

- Since the beginning of 2018, borrowings from banks have grown (Russian) 11.6%, while real incomes have only increased 2.6%. Even this modest income growth would not have occurred without the March presidential election, which saw sweeping increases in payments to government employees. During the summer, incomes only rose by 0.2-0.3%. For the past four years in a row, real income levels in Russia have fallen.

- The main driver of this credit boom has been the Central Bank’s decision to lower the key lending rate by 1.75 percentage points over the last year, meaning interest rates have become more favorable for borrowers. As a result, banks are trying to increase the size and term lengths of their loans so borrowers have to part with just as much money as before. Requirements for borrowers have also been reduced: for example, since the beginning of 2018, banks approved 70% of all mortgage applications (the year before only half of all mortgage applications received approval). And, while borrowing has increased, so has bankruptcy. During the first three months of 2018, the number of bankruptcies grew up 50%.

- All of this might have a significant impact on the quality of the assets held by Russian banks. This week, it became clear that the situation was likely far worse than what is shown by official data. Ratings agency Fitch re-calculated indicators for Russian banks according to the new IFRS-9 standard (which will take effect in 2019). It turns out that, according to the new standard, the share of bad debt held by the top 20 banks is 11% (about $8 billion) — not 5% as the Central Bank claims. According to Fitch, most of the biggest banks would have to use more than half of their own capital to cover bad debts and VTB, the country’s second largest bank, would have to use 95% of its capital. In the event of a new banking crisis, Fitch estimates, two of the three major banks, VTB and Gazprombank, would need to use over two years worth of pre-crisis profits to cover losses. Both banks would have to ask the government for a bailout.

Why the world should care

Each banking crisis makes the Russian economy more state-owned and closed to the outside world. In the event of problems, state-owned banks receive Central Bank support and private banks either get taken over by state banks, or go bust.

4. The Kremlin is solving the self-created problem of criminal charges for “extremist” social media posts

What happened

U.S. internet companies have been taking the blame all year for personal data leaks, and now also for tracking users’ geographical locations. But users of Russia’s largest social media network, Vkontakte, have more immediate problems: they face prison sentences for reposting memes that Russian law deems “extremist”. The owner of Vkontakte, Russia’s largest internet holding Mail.Ru Group, has long been accused of cooperating with the security services. At the beginning of August, Mail.Ru Group unexpectedly launched a campaign to fight the criminalization of social media users.

- The first criminal charges for social media posts were in the early 2010s. Charges were usually brought under the law on “incitement of hatred or enmity, as well as the humiliation of human dignity” and, in most cases, the reposting of a meme was the trigger. These could be pictures with Nazi symbols or cartoons making fun of government officials or religion. In 2017, 228 people faced such charges and 47 of them received prison sentences. Only in six cases did the accused publish their own material; in all other cases they reposted pictures.

- 96% of these criminal charges were brought against postings on Vkontakte. This social network has long been accused (Russian) of passing data and even the personal conversations of users to police investigators without court permission. Mail.Ru Group has generally ignored these accusations, but at the beginning of August it suddenly launched a campaign against criminal charges for social media posts. The company has called on the State Duma to amnesty those convicted and appealed for a change to the law. Even state-owned TV channels began to cover the problem: analytical agency Medialogia calculated for The Bell that in April, May and June, state-owned TV ran only 3 pieces about criminal charges for social media posts, but in the week beginning Aug. 5, 11 such pieces were aired. There has never before been so much official attention. This week, the government also joined the campaign. The Communications Ministry and the presidential human rights ombudsman have both now advocated for a change to the law.

- Such a coordinated campaign would never have been possible if Putin hadn’t highlighted the issue in June. During the president’s annual call-in show, he was asked about invented criminal charges for social media commentary and he asked a pro-government NGO to work with the General Prosecutor’s Office to come up with a solution. Of course, all the questions during such events are highly choreographed. So, why did the Kremlin want this campaign? It allows the government to kill two birds with one stone. On the one hand, the TV coverage underlines for ordinary Russians that you really can go to prison for a critical social media post, while, at the same time, the Kremlin mitigates its reputation as a vicious regime. Young social media users are also shown that the government is correcting mistakes made by the overzealous, repressive system (despite the fact that the government itself created this system).

Why the world should care

This story clearly shows how the Russian government can manipulate public opinion — and highlights the role that major tech companies play. These companies continue to deepen their cooperation with the state, inching closer to the Chinese model.

Anastasia Stognei, The Bell