Coronavirus takes hold

Hello! This week our top story is about battering taken by stock markets and the ruble and how the government is planning to keep Russian economy on track. We also look at Russia’s changing response to the coronavirus epidemic, an interview in which Putin revealed his instinctive disdain for business, and the death of famous writer and radical Eduard Limonov.

Can Russia save its stricken economy?

This week saw Russia take a huge economic blow as stock markets and the ruble collapsed. The government announced a raft of rescue measures, but they have been criticized by experts for being light on detail, and incomplete.

What happened. It is obvious to everyone that coronavirus and the catastrophic fall in the oil price will have a huge impact on Russia’s economy.

- One can forget about the possibility of 3 percent annual growth (what Putin promised during his re-election campaign in 2018). Rating agency Fitch this week lowered its Russia growth forecast — for the second time this year — to just 1 percent. None of the economists who spoke with The Bell expect growth to be any higher than this.

- The first victim of the current crisis was the ruble, which is extremely sensitive to the price of oil. This week, the ruble was the world’s second most volatile currency, after the Mexican peso. As oil prices fell below $25 a barrel, the ruble dived to 80 against the dollar by Wednesday evening, a 4-year low. The ruble has dropped 30 percent this year.

- The Russian equity market also fell sharply this week: the Moscow Exchange dropped 5 percent (it’s down 30 percent in 2020), while the dollar denominated RTS dove 11 percent (it’s lost 50 percent of its value this year).

- The worst performing stocks included state airline Aeroflot, which has cancelled almost all flights to the UK and the United States. The best performers included retailers Lenta and X5, which have benefitted from the panic grocery shopping.

The government’s plan. Officials have said they are prepared to spend 300 billion rubles ($4 billion) from Russia’s reserves to save the economy — about 0.3 percent of GDP. This is actually a relatively modest sum — similar rescue plans announced worldwide have average about 1 percent of a country’s GDP. The government’s plan consists of support for individuals, businesses, and the financial system.

- The government has promised it will ensure that everyone unable to work because of coronavirus will be offered alternative roles, or further education. Sales tax has been lowered on certain products and exports limited (but there is no talk of lifting the embargo on imported food products from the European Union). Banks will be required to refinance loans, and are forbidden from charging interest on those who become ill with coronavirus.

- For businesses, the government has offered a tax holiday, additional loans, and a moratorium on inspections. Separately, there is talk of support for badly-hit industries: particularly airlines and tour operators.

- The Central Bank promised to support the financial system by increasing hard currency sales. It has said it will sell as much as is needed in order to ‘cover the gap’ when the price of Urals crude drops below $25 a barrel.

Why the world should care

The Bell spoke to several economists who criticized these measures as too vague. It is unclear how further education courses will help those who lose their jobs or those who don’t qualify for sick leave because they are not officially employed (Russia has an enormous gray economy). Direct payments would have a much bigger impact, but Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina has said she “doesn’t see the necessity” for these. Considering the low oil price, this all adds up to a bleak future for the Russian economy and ordinary people.

Testing, panic buying & indifference: Russia battles coronavirus

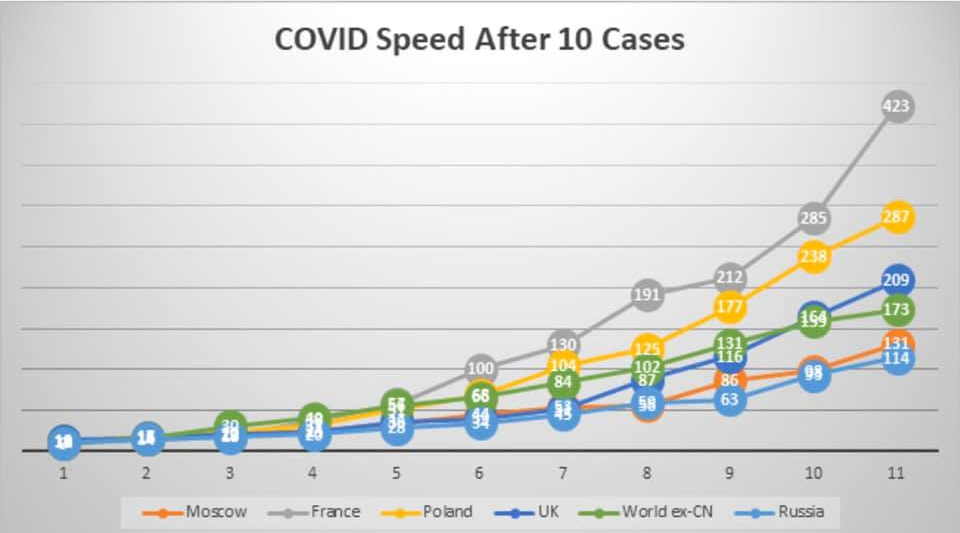

Until very recently, there were very few cases of Covid-19 in Russia. There are various theories for this, from smart protective measures to a dysfunctional testing system. But the epidemic really took hold this week when the number of new cases started rising by 30 a day — and it has been growing exponentially since then. The number of confirmed cases reached 253 on Friday. The vast majority of them are in Moscow.

Strategy. At first, Russia only tested those arriving from China, South Korea and Iran if they showed symptoms (meaning many tourists from Italy were not tested). Later, the list of the countries was expanded, but, still, most arrivals were not tested. It is currently impossible to get a voluntary test, unless you have severe symptoms.

Until this week, there was only one center processing Covid-19 tests. “Russia got stuck because of a fight between different agencies within the healthcare system,” a source told The Bell. Eventually, a consensus was found, and the approach changed dramatically.

Now, another research institute is developing a test. And it will soon be possible to get a voluntary test from private healthcare company Invitro. The Russian Direct Investment Fund announced Monday that it will invest in a super-speed test that can be done in 30 minutes – this got approval from the Health Ministry in a record 3 days. It was also announced that everyone in Russia will be able to get tested, but the logistics are still very vague.

Panic buying. As the number of cases has surged, so has panic buying. Like other parts of Europe, there have been reports of hand sanitizer, toilet paper, pasta, rice, tinned goods, salt and sugar disappearing from shelves. But the item that has been most in-demand amid the growing fears over coronavirus and the falling ruble is buckwheat. Stores across Russia have sold out of the grain, and photos of empty shelves circulated widely across social media. The beloved buckwheat is relatively cheap, and is eaten on its own with butter, milk or oil, or as an accompaniment to meat or fish. While the traditional go-to food in times of crisis, experts (Rus) say Russians actually only eat on average about 3 kilograms of buckwheat a year, meaning that much ends up going mouldy at the back of cupboards.

The authorities sought to calm fears about food shortages. Putin said Tuesday that there was no need to hoard food, and that the situation was stable and, two days later, Trade and Industry Minister Denis Manturov said retailers have supplies for at least two months. Many were quick to point out that two months is not a long time in coronavirus-terms, and officials even addressing the topic of food shortages is very scary for most people.

Casual attitudes. The first serious anti-coronavirus measures were imposed this week as Moscow banned gatherings with more than 50 people. But the metro is still operating and the constitutional change referendum scheduled for 22 April has not been postponed. While schools and universities are closing across the country and many companies in Moscow are sending their employees to work from home, the majority of shops and restaurants remain open as usual.

Outside Moscow, there is a lot of evidence to suggest that coronavirus is seen as an imaginary threat. The most iconic example (Rus) was an infectious disease specialist from the city of Stavropol in southwest Russia who came back from Spain and continued working – until she was hospitalized with suspected coronavirus.

Most speculation this week focused on whether Moscow is going to be sealed off (all transport shut down, no-one allowed in or out). The authorities are actively considering such a step, according to Vedomosti — though City Hall later denied this. According to news outlet Baza it may be implemented when the number of cases hit 800.

So far, the most serious measure has been Russia’s decision to close its borders to all foreigners from Wednesday. Meanwhile, hundreds of Russian tourists got stuck abroad because of closing borders and astronomic airfares — one Aeroflot flight from Athens to Moscow was on sale (Rus) for $6,200. Few evacuation flights have taken place.

Putin shows his disdain for business

There was never much doubt about Putin’s instinctive distrust of business and the market economy. And in an interview with the state-owned TASS news agency released this week, he was direct about it, making a snide reference to “so-called” business. But most people disagree with him: 80 percent of Russians (the highest figure since 2003) think business has a positive impact, according to a recent survey (Rus) by independent pollster Levada Center.

- In the interview, the TASS journalist asked Putin if he sees entrepreneurs as “swindlers by definition”. Putin answered that “there are certain reasons for [thinking like] this, because all so-called business in the 2000s was tied to trade”. “So a trader is a swindler?” the journalist inquired. “Yes,” Putin replied.

- Russians think differently. A total of 80 percent of those polled by Levada Center believe small and medium-sized business is good for the country, and 59 percent feel the same way about big business. Both figures are at 17-year record highs. It is young people and wealthy Russians who have the most positive view of business.

- The main problems for business in Russia are high taxes, corruption and a lack of start-up capital. Pressure from law enforcement is also an issue: 50 percent of those polled believe interest from the authorities means an attempt to solicit a bribe or seize an asset.

- This is not the only contradiction between Putin’s view of the economy and that of ordinary people. In the same interview (Rus), Putin said 70 percent of Russians are middle class, which he defined as those earning over 17,000 rubles ($200) a month. This led to a wave of bewilderment on social media: even by Russian standards, 17,000 rubles is not a lot of money.

Why the world should care

Each year, the state takes a bigger and bigger role in the Russian economy, which looks increasingly unlike a real market. It’s clear from Putin’s comments that this will not change, even though the Levada poll suggests this may be what Russians want.

Firebrand dissident and writer Limonov dead at 77

From his sexual antics in 1970s New York to cheerleading for Kremlin-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine, Eduard Limonov was one of the most uncompromising and colorful characters in Russian political life. He died Tuesday after a long battle with cancer.

- A poet and radical, Limonov’s real name was Eduard Savenko. He grew up in Kharkhiv, Ukraine, and emigrated from the Soviet Union in 1974 after refusing an offer from the KGB to work as an informer. His subsequent life in New York provided the material for his most popular book, It’s Me, Eddie. The fictionalized memoir recounts the narrator’s poverty, sexual adventures, and unhappiness in New York, but it was the descriptions of gay sex that were most shocking for Soviet readers. After New York, Limonov settled in Paris, before returning to Russia in 1991.

- Politically, Limonov was most associated with the National Bolshevik Party that he set-up with nationalist ideologue Alexander Dugin and rockstar Yegor Letov in 1993. Its logo combined Soviet and fascist imagery, and its members were known for their nationalism, quasi-military organization, opposition activism — and leather coats. The party was banned in 2007, although it was later reincarnated as Other Russia.

- A relentless activist, Limonov served 2 years in prison in the early 2000s on terrorism charges, which he denied. In 2009, he began the famous Strategy-31 protests. These were gatherings of his supporters in central Moscow on the 31st of the month to highlight article 31 of the Russian constitution, which guarantees the right to free assembly. Almost without fail, the demonstrations were broken up by riot police and Limonov was arrested as he left his apartment.

- It is difficult to fit Limonov’s political views into any simple category, left or right. He was a prolific writer, a fierce opponent of Putin, and would occasionally cooperate with democracy activists. But he was also an incorrigible narcissist, and came from a fascist tradition that lauded direct action over gradualism, and fetishized violence (the National Bolshevik extremist newspaper, Limonka, was a play on his name as well as being slang for hand grenade). Many of his former friends in the West were disgusted by his association with war criminal Radovan Karadzic in Bosnia in the 1990s, and his support for Russia-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine.

Why the world should care

Limonov was an iconic figure, whose death is a milestone in the passing of Russia’s political leaders of the 1990s. Top officials are more and more just technocrats, while many young opposition activists cannot remember a time before Putin’s presidency.