Government wins temporary reprieve in acrimonious gas price fight with oil companies

Hello! This week we dissect an increasingly bitter tussle between Russia’s oil companies and a government nervous that gas price rises will cause popular unrest. You can also read the highlights of our investigation into Synergy, the big international conference organiser that appears to have an unsavoury private education business in Russia, as well as our analysis of new sanctions against Ukraine and an explainer on why the exposure of the intelligence agents accused of poisoning Sergei Skripal is causing problems for Russian business.

Hello! This week we dissect an increasingly bitter tussle between Russia’s oil companies and a government nervous that gas price rises will cause popular unrest. You can also read the highlights of our investigation into Synergy, the big international conference organiser that appears to have an unsavoury private education business in Russia, as well as our analysis of new sanctions against Ukraine and an explainer on why the exposure of the intelligence agents accused of poisoning Sergei Skripal is causing problems for Russian business.

Government wins temporary reprieve in acrimonious gas price fight with oil companies

What happened

This week, the Russian government managed to avoid a sudden increase in gas prices, despite threats made by the big oil companies. Gas prices are just as big a problem for Russian officials as they are for President Donald Trump, but Russian officials can use non-market means to keep rises in check. While this may seem a good short term option, if truth is told, interference like this may lead to even bigger problems down the road.

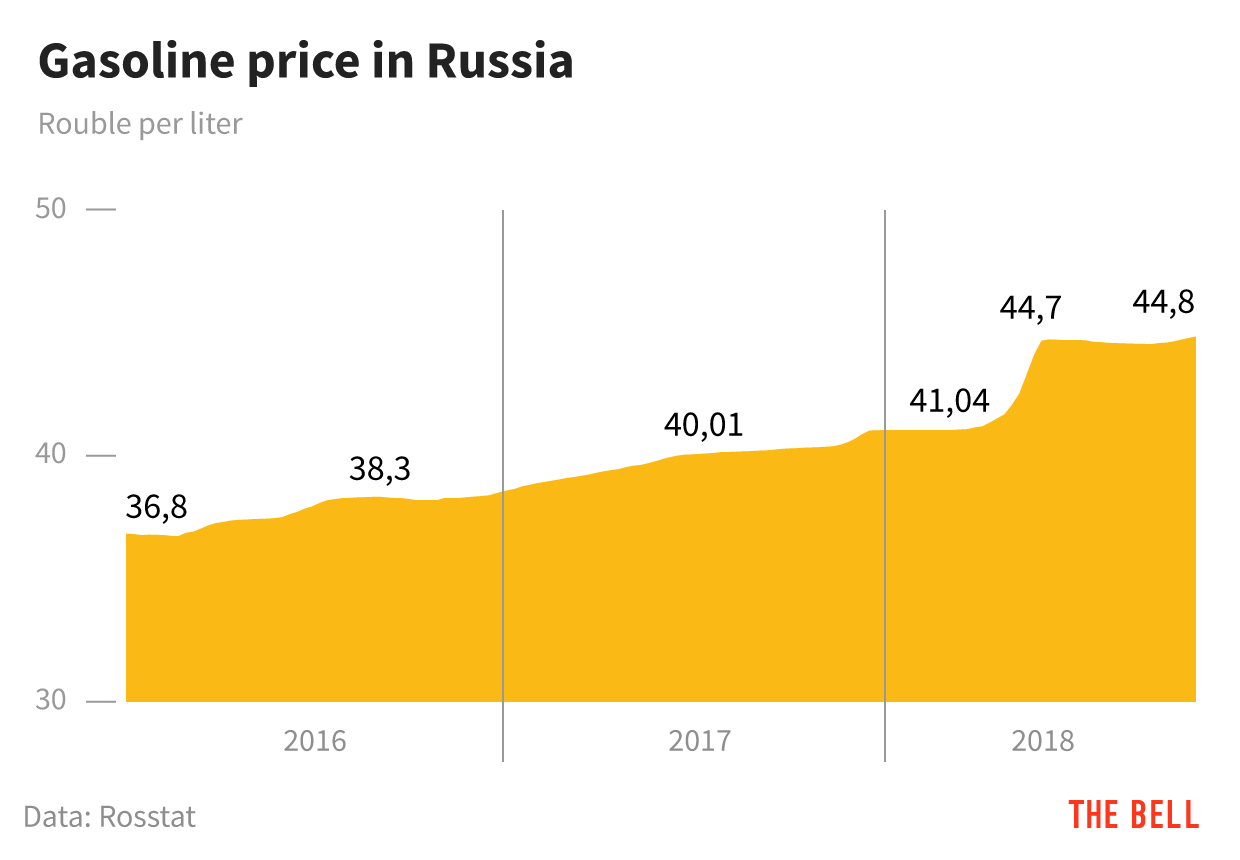

- In June 2018, after the last wave of retail gasoline price hikes, the government convinced the oil companies to freeze prices. By the beginning of October, however, oil companies were losing patience and told the government they intended to increase prices by 10% from the start of 2019. Eventually, the oil companies agreed to hold price until March 2019 — but only because Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev threatened them with a punitive export tax on refined oil products.

- Gas prices are a painful topic for the government and President Vladimir Putin, whose rating fell this summer to its lowest point since 2014 over the unpopular decision to raise the pension age. About a quarter of Russians blame the government when asked by pollsters who is at fault for rising prices at the pumps.

- In the spring of 2018 gas prices in Russia increased by 10% in just two months — from $0.62 to $0.68 per liter. This was due to several factors: Putin had just been safely elected to a fourth presidential term, but also the crisis in Venezuela and new sanctions against Iran meant Russian companies suddenly had more export opportunities. Moreover, exports became more profitable in 2017 because the ruble decoupled from the oil price, meaning energy companies’ costs in rubles stopped growing despite a steady rise in the oil price. This all combined to cause a shortage of fuel on the Russian domestic market, driving up prices. In response, the government acted fast, deploying non-market measures: oil companies were promised subsidies worth 600 billion rubles ($10 billion) in exchange for not increasing prices.

- Since the spring, gas prices have stayed stable, but independent downstream retail and wholesale companies have found themselves inching towards bankruptcy. These companies buy fuel on an exchange, and you can’t sell fuel at a reduced price even if you want to — that would be a violation of anti-monopoly rules. Even if the government turned a blind eye to rule breaking, independent companies would simply buy gas at the lower price and export it. A vicious circle has born, and there is no end in sight.

- On Wednesday, the government won their spat with the oil companies and prices will be frozen at the pump until the end of March 2019. But what will happen then? We asked some analysts. Denis Borisov, the director of Ernst and Young’s Moscow Oil & Gas Center said that if the ruble falls, or remains steady against the dollar, the terms of the government’s agreement with the oil companies may have to be re-evaluated. Raiffeisenbank analyst Andrei Polischuk added that in the long term domestic prices will have to rise, whatever happens.

Why the world should care

The Russian government is more and more frequently using non-market methods. Heading off domestic unrest and protecting the economy from sanctions are such urgent priorities that officials cannot just leave the market to function independently.

The Bell investigates: The Russian private education outfit throwing star-studded parties in New York appears to systematically exploit teenage students in Moscow

What happened

In 2017, Russian company Synergy engaged a selection of celebrity guest speakers to go on stage at New York’s Madison Square Garden. They ranged from Richard Branson to Ray Kurzweil — and the afterparty was hosted by Paris Hilton. Synergy planned to sell tickets for $2,000 to $10,000 each, but ran into problems. At first, they were forced to drop the price, then they started just giving tickets away in libraries and coffee shops. But Synergy hasn’t been put off by this experience and is planning shows in Shanghai and London. In Russia, they attract audiences of up to 25,000 people and makes sizable profits from a private university business. The Bell has investigated how Synergy is run and dug up new details about Vadim Lobov, the company’s owner and one-time guest at Trump’s National Prayer Breakfast.

- Synergy is Russia’s largest private university, a business school and a conference organiser. The university earns more than $53 million a year, significantly more than its closest competitors. But it is the university’s business model that is most interesting: it’s an educational conveyor belt. For the last 16 years, Synergy has attracted 150-200 students from the regions to Moscow, where they are promised they will receive a free education and get work experience. But in reality, these students told The Bell that they work to attract paying students: they visit schools to encourage students to apply to Synergy and work around the clock without weekends for a tiny salary (the company denies this). Moscow court records show that if a student leaves Synergy early, the university demands compensation that can be more than $1,500 per year.

- Until the early 1990s, private universities did not exist in Russia. Once they were legalized, it led to a rash of new institutions offering low quality courses, which tarnished the image of higher education. In the 2000s, the state began to “tidy up” the sector, a process from which Synergy benefited as it acquired 15 major universities together with their students, teachers and real estate. Sources told The Bell that this only happened with the help of Russian education officials.

- Synergy’s founder, Vadim Lobov, is a typical businessman of the 1990s. He started out aged 19 selling flowers in his hometown in southern Russia and then, with friends, he bought a textile factory. After moving to Moscow he studied, lived modestly and tried his hand at everything from business to politics. Eventually he decided to build a private education business. In 2017, Lobov was part of a Russian delegation at Donald Trump’s National Prayer Breakfast. “No one knows how Lobov managed to get himself included in the delegation. But it’s likely he hoped it would be helpful for his international expansion plans,” said political scientist Andrei Kolyadin, who also attended the event.

Why the world should care

Synergy is expanding rapidly and you can find the company all over the world – its university even has a campus in Dubai. The company says it organises “up to 500 forums a year” that Lobov wants see “in all the world’s capitals”. The names Branson and Kurzweil are, of course, big crowd pullers, but before you hand over hundreds of dollars for a ticket, you should understand who exactly you are paying.

Why the unmasking of Skripal’s poisoners is a headache for Russian business

What happened

Revelations about Russian military intelligence officers has unexpectedly hit local business. The surnames and biographical details of the operatives involved in the attack on former Russian spy Sergei Skripal were discovered by searching closed databases used by Russia’s security services. Private Russian companies have for years used these databases to perform background checks on potential employees and competitors but, after the scandal, the security services have begun a crackdown — and access has become much harder.

- When the covers of GRU officers Alexander Mishkin and Anatoly Chepiga were blown (they had identified as Alexander Petrov and Ruslan Boshirov), the FSB began an investigation and has, so far, carried out 60 searches and filed dozens of criminal charges. Access to closed databases has been curtailed. “If in the past it was possible to use them with the help of someone else in the service or an acquaintance, now everyone is nervous and afraid of getting caught. The FSB is taking this seriously,” a former police officer told The Bell.

- Almost every medium-sized or large Russian company has a former intelligence operative as their head of security. One of his main responsibilities is to maintain access to these closed databases, which can be used to learn more about someone than could ever be found out from an official enquiry to the police. This is completely standard practice for heads of security at private companies: they all regularly ask former colleagues in the security services to “run someone’s name” through any one of several such databases.

- The FSB’s investigation won’t completely end access to the databases but it will make it more expensive, according to security specialists and private detectives who spoke to The Bell. At the moment, the cost of one background check on the shadowy information market ranges from $80 to $250.

Why the world should care

If you were surprised at how details about the Russian military intelligence officers spread around the world so quickly — you shouldn’t have been. This new push against leakers shows how simple it is for those in the know to uncover such information.

Russia’s sanctions against Ukraine seen as attempt to interfere in Kyiv politics

What happened

Russia isn’t just sitting back and waiting for new U.S. sanctions — it even comes up with its own sanctions. On Thursday, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev introduced sanctions against 390 Ukrainian officials, businessmen and companies — but the list doesn’t include a single major business owner with significant commercial interests in Russia.

- The Russian government’s decree said the sanctions were “in response to unfriendly actions” by Ukraine and they mandate a freeze on the Russian property, bank accounts and securities of all the individuals and companies named.

- The list is deeply illogical. Almost all of those who feature on it don’t have any assets in Russia that could be frozen, and there is a lot of speculation that being included on the list is beneficial for a political career in Ukraine, where anti-Kremlin feelings run high. “Russian sanctions – when the line to buy a place on the sanctions’ list is longer than the line to buy an iPhone 10”, wrote one Ukrainian deputy on the list, Mustafa Nayyem.

- The list does not include Ukraine’s richest man, Rinat Akhmetov (valued at $5.4 billion by Forbes), whose metals business is heavily tied to Russia. But it does include politician Yulia Timoshenko, who will likely be President Petro Poroshenko’s main opponent in May presidential elections. Timoshenko, currently leading in the polls, is accused of having links to Russia and many are suggesting that being included in the sanctions’ list will help her distance herself from these accusations.

Why the world should care

The U.S. Congress has blamed the White House for the limited effectiveness of sanctions against Russia (which is partially true). But just compare this with Russia’s sanctions against Ukraine, which have been specially designed not to work. They are pure politics.

Peter Mironenko

Anastasia Stognei contributed to this newsletter. Editing by Howard Amos.

This newsletter is supported by the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley.