Growing optimism for Russia’s economic prospects

Hello! This is Alexandra Prokopenko with your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. In today’s newsletter, we focus on increasing short-term optimism over Russia’s economy and how the issue of personal sanctions on Russian businessmen is splitting the opposition — not the elite

Help us to make our newsletter better

Before we start, we would like to ask you to take a quick survey. It will help us to deliver what you really want to know.

Cautious optimism for Russia’s short-term economic prospects

Russia’s economic indicators are starting to improve and the budget deficit that shocked observers in January has shrunk. Both economic experts and households are increasingly showing cautious optimism. In the absence of further external shocks, such as a sharp fall in Russian energy prices or a new round of sanctions, there is every possibility that the IMF’s prediction (0.3% GDP growth in 2023) will be achieved. The key driver of growth and optimism is internal demand, primarily fuelled by generous budget spending, according to Central Bank analysts. However, if the spending stops, so will the growth.

Government spending growth

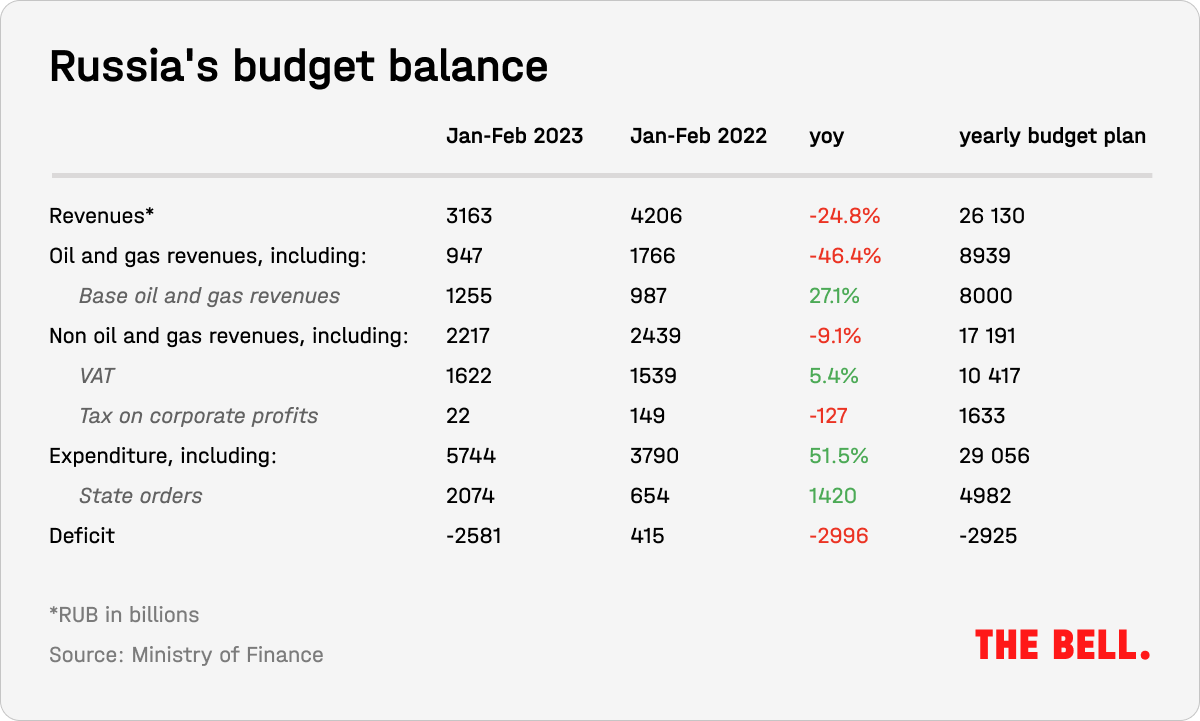

Expenditure in January and February was 5.75 trillion rubles, up 51% on the equivalent period last year. At the same time, revenues fell by almost a quarter, to 3.16 trillion rubles. The budget deficit was 2.5 trillion rubles, almost 88% of the planned figure.

At the same time, February’s figures look a bit better than January’s. The monthly budget deficit for January was 1.8 trillion rubles but in February it fell to 0.8 trillion rubles. But an increase in spending is also slowing: throughout February expenditure was 2.63 trillion rubles, compared with 3.12 trillion in January. This is already fairly close to historical norms (in February, the government spent 8.9% of its entire planned expenditure for the year, compared with a historical norm of 7%), the Solid Figures Telegram channel noted. More detailed data on budget spending shows that, in the second half of February, there was a slowdown in expenditure. The Finance Ministry continues to explain the high level of spending at the start of the year on advance payments for government contracts.

It’s quite possible that the Finance Ministry is correct. But there is an important side-effect to increased budget expenditure at the start of 2023 — it goes a long way to offsetting the generally unfavorable economic background.

- In the manufacturing sector, high expenditures contributed to increased production, Central Bank analysts pointed out. In January (February’s figures will not appear until late March), the biggest growth was in sectors related to the military-industrial complex: vehicle manufacture (including aviation technology and shipbuilding) was up 27.4%; computers, electronics and optical products was up 5.5%; clothing was up 5.5%; metal components (not including machinery and equipment) was up 3.6%.

- In the raw materials sector over the same period production of coal (-3.5%), oil and gas (-3.2%) and metal ores (-3.1%) all fell. However, there was growth (+14.2%) in the production of other raw materials, including stone, gravel and sand (this suggests growth in the construction industry likely fueled by the advance payments mentioned by the Finance Ministry). In early March, the government allowed companies working in public procurement to receive up to 50% of the value of their contracts in advance. Companies engaged in capital expenditures (for example, road building) in annexed Ukrainian territory can receive up to 90% in advance. Construction contracts in these areas go to firms linked with the Russian military, security forces and officials.

Consumer-driven growth

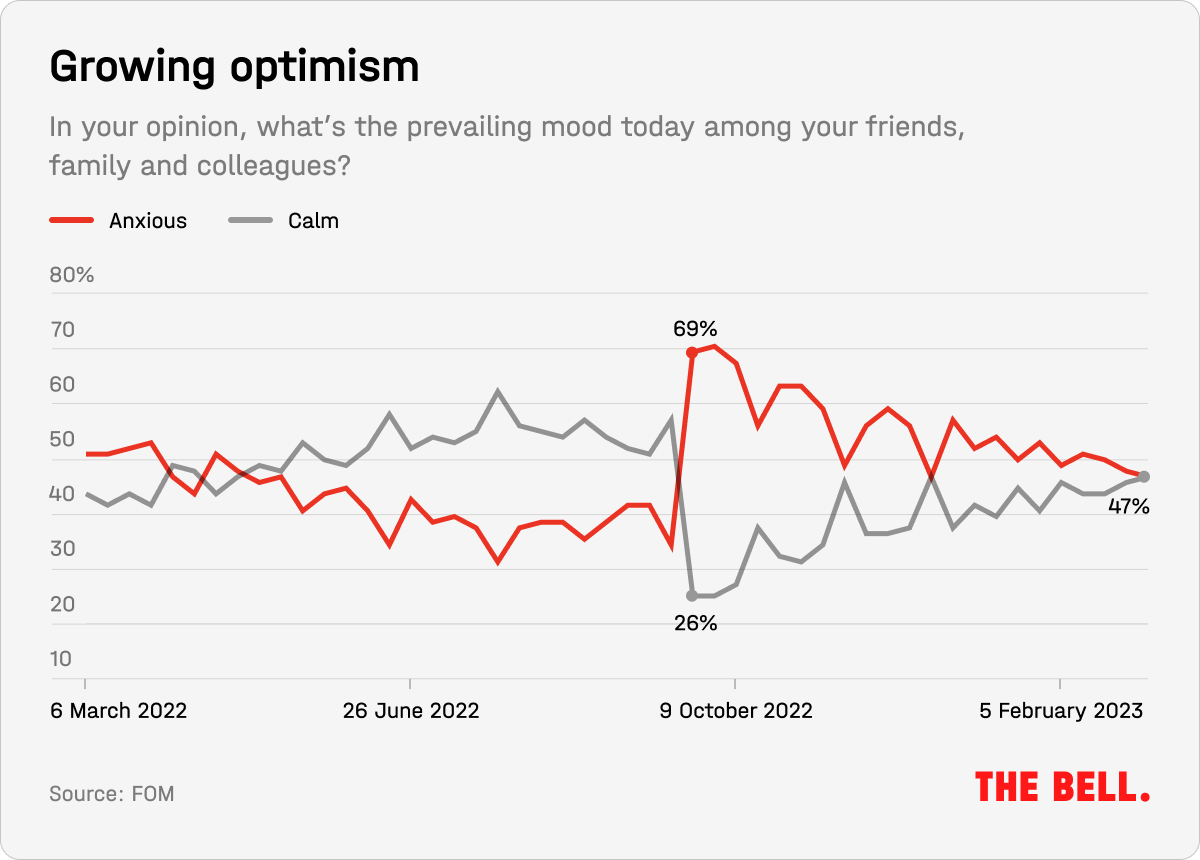

The second important factor in economic stabilization has been growing consumer optimism — and related consumer spending. Studies commissioned by the Central Bank show that consumer confidence, which collapsed following Russia’s mobilization in the fall, has almost entirely rebounded. Propaganda plays a role in this — most independent media is blocked in Russia and state media try their very best to spew out positive headlines.

Economic indicators also point to improving consumer sentiment. Spending has stabilized. This is helped by a labor shortage that is driving up incomes (companies increased salaries for employees who did not flee abroad as a result of the war and mobilization). The flipside of increased consumer confidence, of course, is greater inflation risks.

Business sentiment is also improving: in February the PMI index reached a record 53.6 points, its highest level since 2017. Business confidence is growing on the back of an increase in new orders, according to analysts from credit rating agency S&P. Although most of this comes from domestic clients — exports “are falling even further.” At the same time, the real situation in the manufacturing sector is close to stagnation, according to Vladimir Salnikov of economic think tank CMASF.

A decline in exports significantly limits the potential for business growth. Meanwhile, logistical problems make it harder to cash in on the revival of the Chinese economy following the end of Beijing’s Covid restrictions. Russia’s reduction in oil production will be a blow to manufacturing and transport that will be reflected in GDP figures for the second quarter.

The big challenges

The two major challenges facing Russia in 2023 are revenue shortfalls and inflation. Although changing oil taxation and a one-off payment from businesses can give the state’s finances a temporary boost, they cannot fundamentally change the situation.

The Finance Ministry is unlikely to remain within its declared budget deficit target of 2.9 trillion rubles or 2% of GDP. The government can, of course, still plug that deficit using the National Welfare Fund and by taking on debt. But that, in turn, forces the Central Bank to maintain a tight monetary policy for longer.

Why the world should care

The latest economic figures give Kremlin propaganda another chance to shout from the rooftops that all is well. But that’s not the whole story:

- As domestic demand is being driven by the state via the defense sector and construction, it means growth will fall when expenditure falls.

- Demand is falling in sectors not linked to state spending and the defense industry. And the government’s current approach makes inflation more likely. In addition, it’s not a long-term solution. Sooner or later state-driven will no longer be possible — it’s unlikely the defense industry will successfully switch to producing high-quality consumer goods. Even the IMF, which has an optimistic prognosis for Russia’s economy in 2023 believes that the mid-term prospects are not good.

Western sanctions split the Russian opposition

Western sanctions against billionaire Russian businessmen have not yet brought about a split among the Russian elite — but they have led to significant disputes within the Russian opposition (all of which is now based outside of the country). One of top opposition politician Alexei Navalny’s leading supporters, Leonid Volkov, was forced to leave his job as head of the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) this week amid accusations he lobbied the European Commission to lift sanctions on Alfa Group shareholders Petr Aven, Mikhail Fridman, Alexei Kuzmichev and German Khan. Volkov’s letter in support of Fridman and Aven emerged at the start of March — it was initially released by the former editor in chief of Ekho Moskvy Alexei Venediktov, who FBK accuses of taking money from Moscow City Hall.

In addition to Volkov, other opposition figures also signed an appeal to lift sanctions against the owners of Alfa Group. Signatories included co-founders of Dozhd TV Natalia Sindeeva and Vera Krichevskaya, former deputy prime minister Alfred Kokh, politician Leonid Gozman, journalists Sergei Parkhomenko and Leonid Parfyonov, businessman Yevgeny Chichvarkin and economist Vladislav Inozemtsev.

The signatories claim that Alfa Group was never close to Vladimir Putin and, on the contrary, displayed a “lack of political engagement.” Fridman, the main shareholder, was described as “a friend of the late [opposition politician] Boris Nemtsov”, who “always strongly distanced himself from contact with Vladimir Putin (they never met in private).”

Detail: The Financial Times discovered Friday that Fridman and Aven are ready to divest their 45% stake in Alfa Bank, Russia’s largest private bank, in order to have sanctions against them lifted. Their long-term partner, the least prominent of Alfa Group’s founders Andrei Kosogov, is willing to buy a stake worth 178 billion rubles ($2.3 billion) held by Cyprus-based ABH Holdings. He currently holds 41% of ABH Holdings after buying out the shares of German Khan and Alexei Kuzmichev, both of whom remain under sanctions.

Since war broke out, Aven and Fridman have distanced themselves from Russia as far as possible (although Khan returned to Russia). However, it would be a big exaggeration to say they are distant from the Russian authorities. In 2019, Fridman took part in Putin’s traditional pre-New Year meeting with top businessmen. And in 2013, Alfa Group and their partners received $27.7 billion from state-owned Rosneft for a stake in a joint venture with BP. The deal went ahead with Putin’s personal approval.

At present, there is no mechanism to lift personal sanctions against individual Russians, so those affected are currently seeking legal solutions (for more about the mood among the Russian elite and their sanction-busting strategies, see here). Their lawyers often recommend collecting testimonials from Russian opposition figures respected in the West.

Why the world should care

Questions about who deserves to face sanctions are somewhat philosophical. So far, though, they have caused more splits in the opposition than among the Russian elite. Moreover, faced with a choice between the unknown prospect of escaping sanctions and the familiar demands of Putin and his security forces, most are choosing the devil they know. Reviewing personal sanctions, or creating a mechanism to remove them, would likely turn oligarchs away from Putin. In the meantime, they are fighting back: recently a European court lifted sanctions against the mother of tycoon and mercenary leader Yevgeny Pigozhin.

Figures of the week

- Inflation slowed almost twice in February, according to Rosstat: to 0.46% after 0.84% in January. Annual inflation also slowed to 11% from 11.4%. During the week of February 28 to March 6, prices stabilized around zero. The biggest contribution to the growth of prices was made by: food +9.3% m/m; services +13% m/m.

- On March 1, Russia’s National Welfare Fund (NWF) was worth 11.1 trillion rubles (up 299 billion rubles for the month, 672 billion rubles since the start of the year). Its liquid assets are worth 6.5 trillion rubles (up 112 billion for the month, 314 billion rubles since the start of the year). The NWF increased due to the redemption of Yamal-LPG bonds, an increase in Sberbank shares and the weakening ruble. In February, 7.4 billion Chinese yuan (a little more than $1 billion) and 12 tons of gold (about $700 million) were withdrawn. The Finance Ministry sold these assets to the Central Bank for 131.7 billion rubles to replace lost oil-and-gas revenues. The Central Bank mirrored these trades on the market by selling a similar amount of yuan (the Central Bank cannot sell gold).

- There was a 12-fold fall in profits in the Russian banking sector in 2022, the Central Bank reported. Almost half of the banking sector’s reserves (1.1 trillion rubles) are now connected with various frozen assets (Eurobonds, subsidiaries, loans to non-residents etc). The banks’ forex assets fell from $331 billion to $290 billion (part of which is frozen), forex liabilities fell from $353 billion to $259 billion. The yuan began to appear on banks’ balance sheets.

- Russian firms make half of their foreign trade settlements in yuan. At the end of 2022, the share of dollar and euro payments for Russian exports fell to 48%, the Central Bank said. Almost all the rest were settled in rubles and yuan (34% and 16%), with currencies from other “friendly” nations amounting to 2%. At the start of last year, 87% of trades were made in dollars and euros, 12% in rubles and 0.5% in yuan.

- When paying for imports, the dollar and euro share fell from 65% to 46%, but they were not replaced by the ruble — but by the yuan. The Chinese currency’s share increased from 4% to 23% while the ruble’s share fell slightly from 29% to 27%.

What to look out for

- Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs Congress — March 16

- Central Bank board meeting to set interest rates— March 17

Further reading

- Lies, damn lies and statistics — how many prisoners has Wagner really recruited? Judith Pallot points out why any inmate recruitment estimates based off Russian federal prison data is shoddy journalism and should be treated with caution

- Chasing Russia’s shadow reserves Martin Sandbu uncovers how the how the financial infrastructure works, and what the new reality of reserves might look like

The author of this newsletter is one of Russia’s leading writers on this topic: independent economic analyst Alexandra Prokopenko. Alexandra worked as an advisor at Russia’s Central Bank and Moscow’s Higher School of Economics from 2017 to 2022 — and before that she was an economic journalist for Vedomosti, then Russia’s leading business newspaper. Today, Alexandra is a columnist at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and a visiting Fellow at the Center for Order and Governance in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia at the German Council on Foreign Relations. She holds an MA in Sociology from the University of Manchester.

Wrtten by Alexandra Prokopenko

Translated by Andy Potts