How Russia uses China to get round sanctions

Hello! We took a break last week to bring you a special newsletter on the shock news of the death of opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Here is your slightly delayed weekly guide to the Russian economy. Our top story is about how China is helping Russia skirt Western sanctions. We also look at the Central Bank’s decision to hold interest rates at 16%.

Made in China: Russia increases imports of both consumer and dual-use goods from China

Due to sanctions, Russia no longer has free access to high-tech Western imports. But a rapid pivot to the East has helped Moscow avoid critical shortfalls, with supplies from China playing a particula rly vital role and having jumped sharply over the last two years. The surge in trade between the two countries is not just about more cars and household goods flowing into Russia, but also dual-use technology essential for Moscow’s military-industrial complex.

What's going on?

After the invasion of Ukraine, most of the world's leading economies — China excluded — imposed sweeping sanctions on Moscow intended to cut off the supply of high-tech products used by Russia’s defense industry. Scrambling for an urgent workaround, Russian companies massively increased their imports from a host of neighboring countries that had not imposed sanctions on Moscow and could still freely trade with the West. Companies in those countries, in turn, boosted their purchases of goods from Europe.

Alongside this intermediary scheme, China also played an important role in replacing Russia’s lost imports. So vital is China to the Russian economy now that President Vladimir Putin said Beijing and Russia’s relationship was “without borders.” Russian imports from China reached a record $111 billion in 2023, according to Chinese customs data analyzed by The Bell — up 47% on 2022, and 65% higher than in 2021, the last full year before the invasion.

High-tech goods are among the top three Chinese exports to Russia. That’s no surprise: under sanctions, many Russian companies had to find new sources of equipment, spare parts, electronics and vehicles. In 2023, Russia significantly increased its imports of computers from China, as well as compressors, machine tools and their spare parts, turbines, optical devices and other advanced manufacturing equipment.

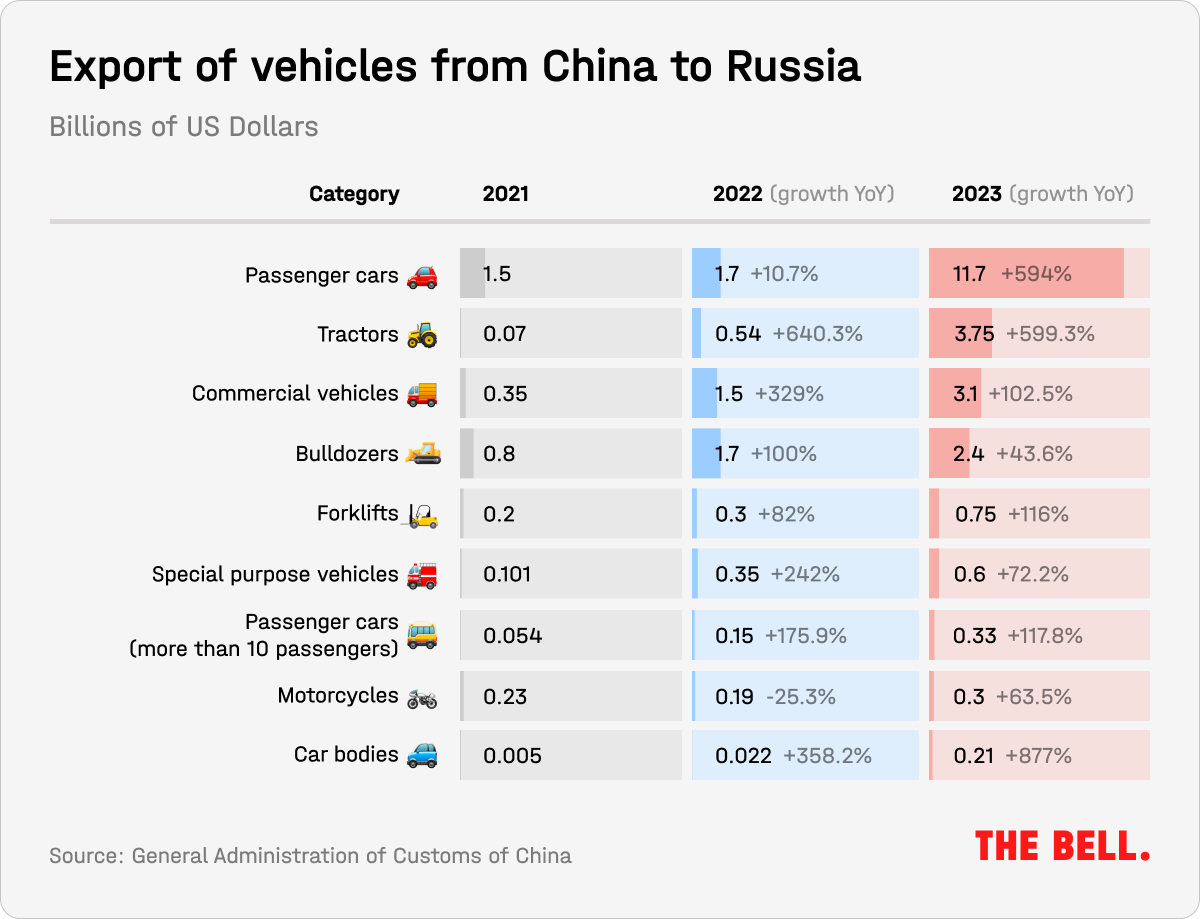

Imports of Chinese cars became perhaps the most obvious symbol of Moscow and Beijing’s rapidly developing trading partnership. After many popular Western carmakers left Russia, Chinese cars flooded the market, becoming the most popular foreign models on Russian roads. Some 19 new Chinese car brands entered the Russian market in 2023, according to the specialist Avtostat agency. European automakers completely dropped out of the top 10, with Chinese firms taking up six of the top ten spots. It’s entirely possible that this year the same ranking will comprise only Russia’s Lada and nine Chinese auto brands, Avtostat analysis suggests. In dollar terms, exports of passenger cars from China to Russia jumped six-fold in 2023 — up from $1.7 billion to $11.6 billion, according to Chinese customs data.

It is not just passenger cars that Russia is buying in huge quantities from China. Over the past two years, Russia has also accelerated its purchases of industrial vehicles, like tractors, trucks and road-making equipment. This is happening at a time when Russia's own leading auto manufacturers (Kamaz, Ural and GAZ) are overwhelmed with orders from domestic law enforcement agencies and at the same time are trying to source new local components to replace those lost thanks to sanctions. That has left them unable to respond to demand in Russia’s stretched civil and private sector.

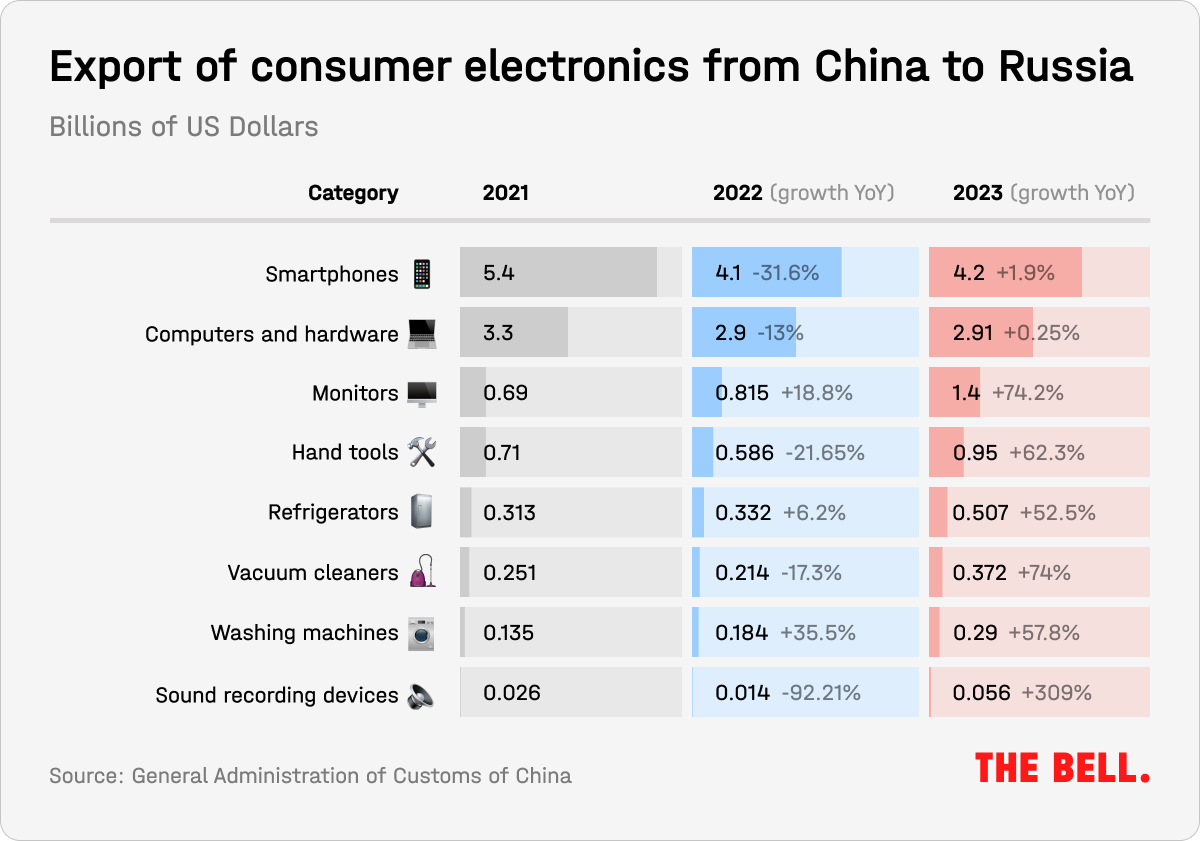

China has also substantially increased its sales of popular consumer electronics to Russia: monitors, fridges, vacuum cleaners, washing machines and the like. Despite jumping, sales of two of the largest categories of high-tech goods — phones and computers — have not returned to pre-war levels.

Under sanctions, Russia has gone from being an insignificant market for China to being a moderately important one. And the connection is only going to continue intensifying, says Alexander Gabuyev, director of the Carnegie Berlin Center for the Study of Russia and Eurasia and an expert on China. “Western goods have left, accessing them is getting harder and more expensive, we need sustainable alternatives that won’t be ‘snuffed out.’ Where can we get them? China,” he said, explaining Russia’s logic.

In 2022, Russia was China’s 16th largest export market, behind the likes of some surprise countries such as Mexico and the Netherlands, according to Beijing’s statistics. But by 2023, Russia had jumped to seventh — trailing only the United States, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and India.

The most popular currency for settling imports is the Chinese yuan, which is used in 37% of Russian import transactions, according to a recent Central Bank report — up by more than 30 percentage points since January 2022.

Military exports

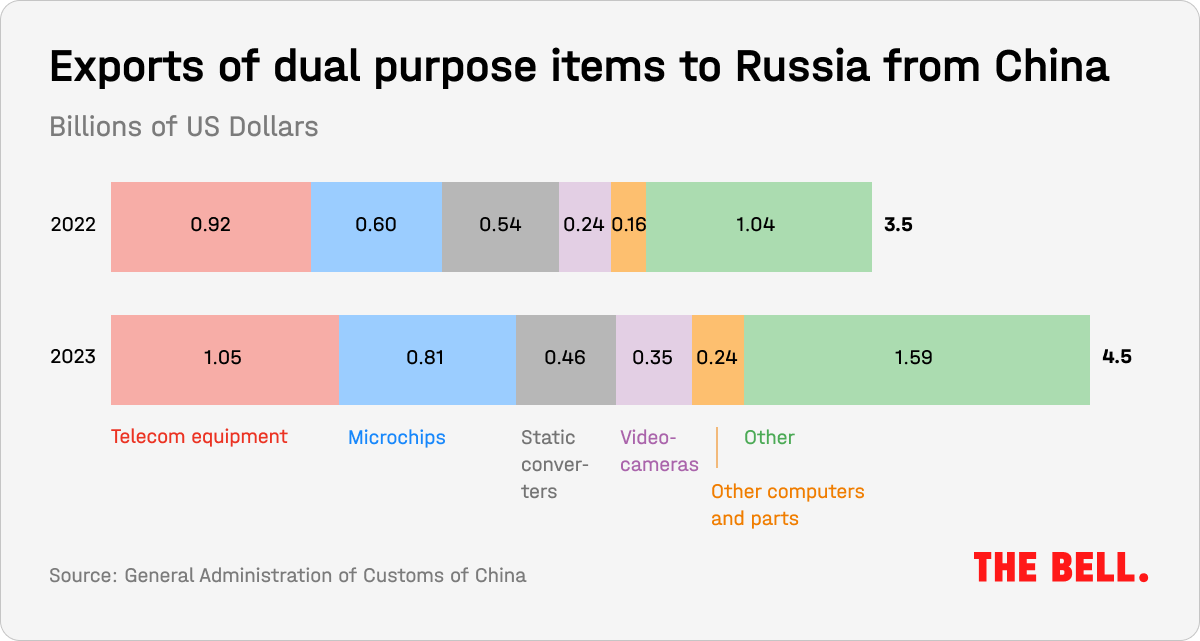

But China has not just increased its exports of purely civilian and consumer products. Exports to Russia of dual-use goods increased by at least $1 billion during 2023, The Bell calculated.

Last year China exported $4.5 billion worth of goods from a list of 45 products designated as critical for Russia’s defense sector by the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) (part of the Department of Commerce) and authorities in the EU, Japan and the UK. The list includes various integrated electronic circuits, computers, navigation devices, cameras, semiconductors, transistors, ball bearings and oscilloscopes. Sales to Russia were up 28.6% on 2022 levels and consisted primarily of dual-use goods — those that can be used either for civilian or military purposes — such as telecoms equipment, static converters (to change currents or voltage), processors and cameras.

In Feb. 2023, The Wall Street Journal reported that state and private enterprises in China were supplying dual-use goods to sanctioned Russian companies. In particular, navigation equipment for Mi-17 military transport helicopters, parts for Su-35 fighter jets, and radars and antennas for RB-531BE jamming systems, an electronic warfare tool, were supplied from China.

Chinese suppliers are concerned about being hit with secondary sanctions, but not enough to stop them delivering to Russia, Carnegie’s Gabuyev believes. They think it is possible to fight off accusations of violating sanctions and provide legitimate explanations for their sales to Russia, he explained.

Moreover, some companies that trade with Russia are already under sanctions, while others that work with the Chinese military believe that they will be sanctioned at some point anyway, Gabuyev added. “Accordingly, if there is an opportunity to develop business in a new market, why not take it?”

The threat of being hit with sanctions has so far only appeared to influence the financial sector, in particular the Chouzhou Commercial Bank, a key player in Chinese-Russian trade that settles transactions with Russian importers. Citing documents provided to Russian importers, the Vedomosti newspaper reported that ahead of the Chinese New Year, the bank halted all operations with Russian clients, delaying transactions until at least March. In addition, at least three of China's big four banks — Bank of China, China Construction Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China — have tightened their checks on cross-border transactions with Russian companies. Despite the apparent restrictions, a source close to one Russian business association told the newspaper that there is no panic just yet — payments are being made, they are just taking longer than before.

Russia's Central Bank holds rates unchanged

The Central Bank called an end to its run of interest rate hikes — for now at least — leaving the key rate at 16% in its first meeting of the year. Russia is still facing strong inflationary pressures and domestic demand is stronger than companies’ capacity to boost production due to ongoing labor shortages, the bank said in a statement. In effect, this means that the Russian economy will continue to overheat.

Inflation is running at an annual rate of 7.4%, ahead of the bank's target of 4%. The Central Bank admitted that it will need to maintain a tight monetary policy if it wants to bring the pace of price rises closer to that target level. In 2024, the average annual base rate will be between 13.5-15.5%, Central Bank chair Elvira Nabiullina said in a press conference, meaning the regulator sees some scope for cuts later this year.

But those who had seen the bank cutting rates by 50 basis points as early as March will have been “saddened” by its stance, economist Dmitry Polevoy wrote after the decision. The Central Bank’s forecast range suggests that it won’t cut rates for the first time until between July and October, Bloomberg Russia’s chief economist Alexander Isakov reckons.

Governor Elvira Nabiullina also said that Russia faces the possibility of inflation coming down, saying demand for goods and services could decline faster than she currently expects in its baseline forecast. She also said the public’s increasing propensity to save — amid high returns on cash holdings — combined with a slowdown in consumer activity and cooling demand for imports was beginning to create the conditions needed for Russia’s economy to return to a more balanced growth path.

Figures of the week

- Russia’s January inflation rate came in at 7.4% in annual terms, the Rosstat federal statistics agency reported last week — above analysts’ expectations (1, 2, 3). Judging by the weekly data, prices continued to rise at the same pace in the first two weeks of February. The persistently high inflation rate is being maintained largely by prices for non-regulated services (+10.6% SAAR), which is the most stable part of the basket. This means that a steady decline in inflation, despite the high Central Bank rate, will have to wait.

- After a moderate January, the Finance Ministry sharply increased federal spending in February. Spending was estimated at 2.7 trillion rubles ($29.1 billion) for the whole of January, while in the first two weeks of February alone it approached 2 trillion rubles ($21.6 billion). The spending plan for the entire year amounts to 36.7 trillion ($397 billion). Just like last year, which saw large deficits in the first months of the year, the higher outlays are mainly advance payments for government contracts.

- According to Eurostat, Russia's trade turnover with the EU in 2023 fell by more than two-thirds. Exports to the EU amounted to 51 billion euros ($55 billion), while imports were 38 billion euros ($41 billion). Despite all the sanctions imposed by Brussels, the EU still imported around 29 billion euros ($31 billion) of oil, oil products and natural gas from Russia, as well as ferrous metals, nickel, aluminum and fertilizers.

- The threat of secondary US sanctions, which has knocked Russian companies’ ability to settle payments in Turkey, has begun to affect physical trade between the two countries. According to Reuters, some Russian exporters have not received payments from Turkey for two to three weeks. As a result, preliminary data for January showed a 39% drop in exports from Turkey to Russia compared to January 2023. Overall trade between the two increased 16.9% in 2023 to $10.9 billion.