Kremlin hopes for Erdogan victory as Turkey goes to the polls

Hello! This is Alexandra Prokopenko with your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. This week we focus on the Turkish elections and what the outcome could mean for Turkish-Russian relations. We also look at how the Central Bank sees vulnerabilities of the financial sector.

High stakes for the Kremlin in Turkey’s presidential elections

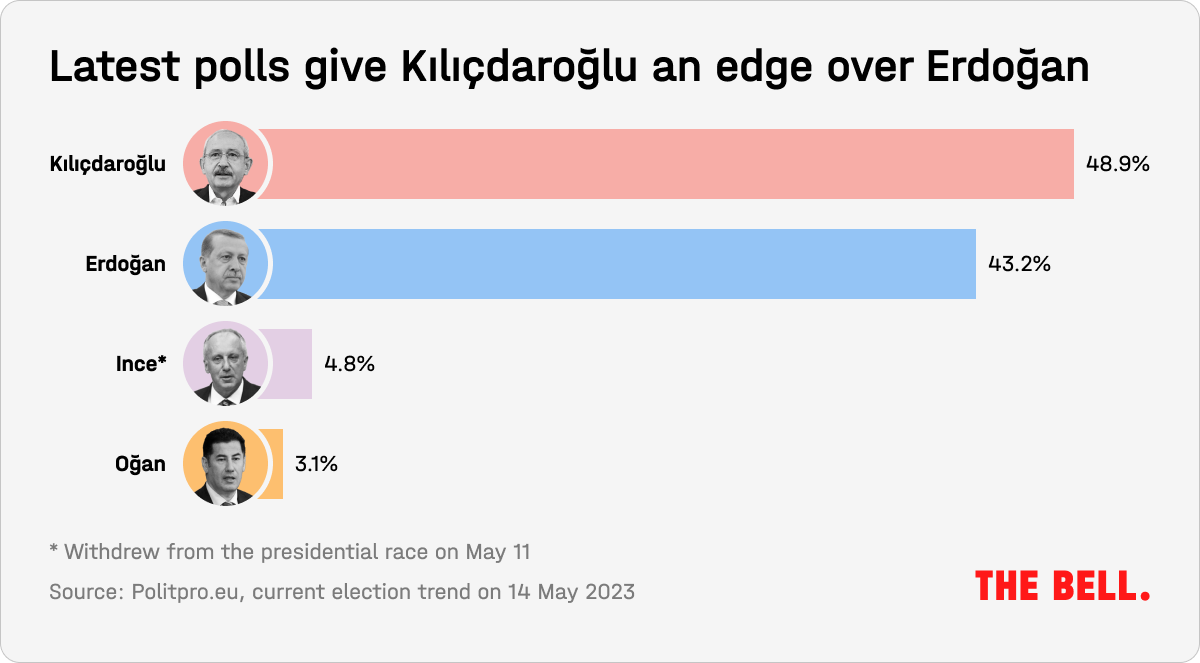

This Sunday will see elections in Turkey that could bring an end to President Recep Erdogan’s 20 years in power. The vote will almost certainly go to a second round and the latest polls suggest opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu is the frontrunner. Erdogan is a key partner for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkey is Russia’s most important hub for international trade and travel — Ankara has provided Russia key support, helping it to withstand Western sanctions since the invasion of Ukraine last year. Let’s look back at how relations between Moscow and Ankara have developed in recent years, and assess whether an opposition victory might be dangerous for the Kremlin.

Who is the alternative to Erdogan?

In these elections, Erdogan is seeking a third presidential term. Such a move was made possible in 2017 when a constitutional referendum led to Turkey switching from a parliamentary republic to a presidential state. Faced with the prospect of another win for Erdogan, who has been leader for 20 years (from 2003 to 2014 he was prime minister), Turkey’s opposition put forward a single candidate to stand against him. This is Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the center-left leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP).

Kilicdaroglu’s key elections pledges:

- Return Turkey to a parliamentary republic

- Limit presidential terms (possibly allowing for a single seven-year time in office)

- Reduce inflation to 10% within two years (in April, annual inflation was 43%)

- Resume talks on Turkey joining the European Union

- Pursue “equal relations” with the EU, U.S. and Russia

As well as Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu, there is one other independent candidate: Sinan Ogan, head of the Turksam analytical center. Another opposition candidate, Mukhharem Ince, unexpectedly withdrew from the race earlier this week.

The Kremlin openly supports Erdogan. For Russia, his defeat would not only mean the loss of a longstanding partner, but it would be seen as a “victory for the dark arts of the West,” which Moscow believes backs the Turkish opposition. The Kremlin always prefers to support semi-autocratic leaders who use anti-Western rhetoric — and Turkey is no exception.

Kilicdaroglu outlined his thoughts on Russo-Turkish relations in a letter to Russian experts last month. His priorities are an end to the fighting in Ukraine and the continuation of the Black Sea grain deal. In the longer term, he hopes to work with Moscow to combat terrorism.

However, he appeared to launch a fierce attack on Moscow on Thursday, writing in a tweet: “Dear Russian friends. You are behind the montages, conspiracies, deep fakes and tapes that were exposed in this country yesterday. If you want our friendship after May 15, get your hands off the Turkish state. We are still in favor of cooperation and friendship.”

The comment was apparently a response to the withdrawal of opposition candidate Ince, who pulled out of the presidential race after a sex tape leaked online.

Perhaps the biggest problem for Moscow could come from another more significant manifesto pledge from Kilicdaroglu — restarting dialog with the EU and strengthening relations with Washington. This will not be straightforward for the West, which would need to resume an unpopular dialog about Turkey’s move towards the EU and persuade Ankara to cool its relationship with Moscow. But a switch in Turkish foreign policy if Erdogan loses threatens Russia with major problems. Since the invasion of Ukraine, Turkey has literally provided Russia with an indispensable “Window to Europe.”

Trading partners

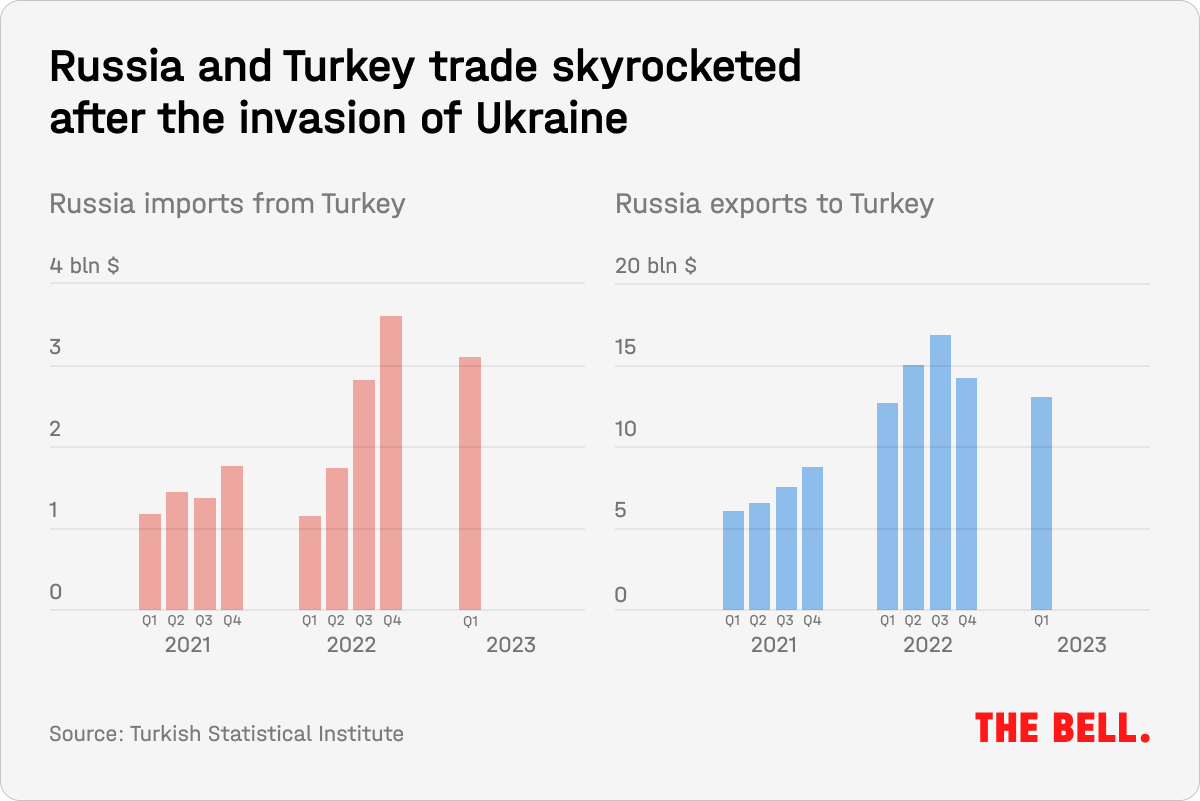

At the end of 2022, Turkey had risen to second place among Russia’s trading partners (in 2021 it wasn't even in the top 10). And Turkish airports have become hubs for international travel for Russians amid sanctions on Russian airlines. In the summer of 2022, there were more than 100 flights a day from Russia to Turkey.

Turkish figures show that the value of the country’s exports to Russia last year increased from $5.8 billion to $9.3 billion. This is not only due to the intensification of two-way trade, but also to the fact that Turkey has become one of the main channels for supplying Western goods to Russia. However, the West is pushing Turkey to stop shipping sanctioned goods to Russia and, under pressure, Erdogan has already tried to make this more difficult.

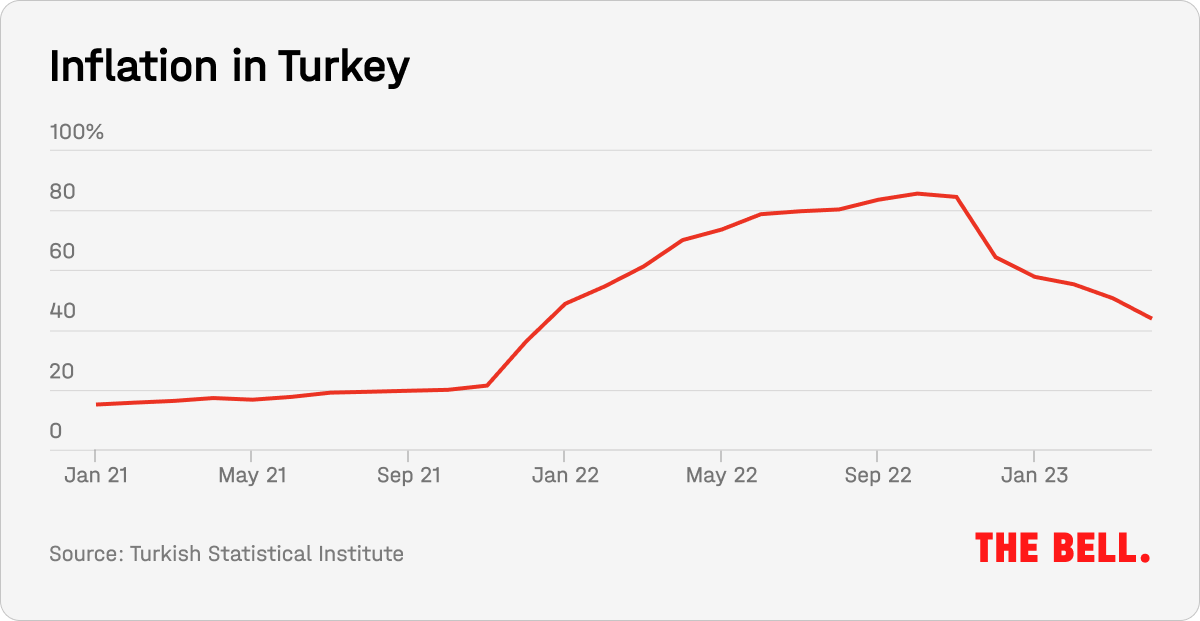

Turkish assistance for Russia comes at a price. Russia offers material aid to Erdogan and, in the event of his defeat, the loss of that support could harm the Turkish economy. Economic instability in Turkey has only increased in recent years due to the reckless measures taken by Erdogan’s government to strengthen the Turkish lira. In 2021, annual inflation in Turkey was running at 36% and in 2022 it was 80%.

Energy partners

Russia’s biggest aid for Turkey has been in the energy sector. The possibility of deferring payments for Russian gas is a key pledge in Erdogan’s election campaign. State-owned Gazprom has agreed to defer $4 billion worth of payment (with $600 million already delayed until 2024), a source told Reuters this week. Notably, Russia has made no official statement about this — so, if the opposition wins, Gazprom can quietly forget about its generous offer.

Russia last year helped Erdogan prop up the lira in another way — by transferring more than $15 billion into the accounts of a specially-created Turkish company that will build the Akkuyu atomic energy plant. A few weeks ago, the first fuel was loaded into the plant and Erdogan and Putin watched the ceremony on video.

Rosatom’s contract to build Turkey’s Akkuyu nuclear plant differs from the company’s other projects in that it uses a build-own-operate (BOO) business model in which Rosatom retains ownership and expects to make a profit by selling electricity to Turkish firms. Since Rosatom has provided everything at its own expense — the fuel, the plant and staff — the BOO contract greatly simplifies (for Turkey) the otherwise extremely complex process of launching a civilian nuclear power program.

In October, right after the explosion on the Nord Stream pipeline under the Baltic Sea, Putin suggested the establishment of a gas hub in Turkey. In effect, this would be a center to sell Russian gas to buyers in southern Europe. The Kremlin proposed supplying gas from Russia and other nations (including Algeria, Qatar, Iran, Azerbaijan, Oman and Turkmenistan), as well as gas from Turkey’s Black Sea fields. But it’s doubtful whether the project as envisioned by Moscow could go ahead without Erdogan.

Diplomatic leverage

In the last few years, the balance of power in Russo-Turkish relations has shifted in Ankara’s favor. Previously, Turkish diplomats had to beg Moscow to allow Turkish tomatoes back to the Russian market after the Kremlin imposed a ban when Turkey shot down a Russian fighter jet operating in Syria. Now, the Kremlin’s reliance on Ankara is so great that, in November, it took Erdogan just two days and one phone call to get Russia to return to the Black Sea grain deal that it had attempted to terminate. None of Moscow’s conditions for agreeing to prolong the deal were met, Russia’s Foreign Ministry said at the time, but that did not stop an extension of the deal in March of this year. Talks over a new extension are ongoing and, according to Turkish sources, are likely to be agreed.

Turkey benefits politically from the grain deal: the agreement was signed in Istanbul and Erdogan personally agreed terms with Putin. Moreover, Ankara gains more than political prestige: as part of the initiative, Turkey received 3 million tons of Ukrainian grain that Turkish companies are processing. If the deal collapses, it would be an economic blow.

Why the world should care

Even if Erdogan wins, he will likely need to take steps to meet some of the demands of Turkey’s pro-Western voters. At the same time, Russia’s ever-increasing dependency on Turkey puts Putin in a difficult negotiating position. If the opposition wins in Turkey, Russia will have to rebuild relations and negotiate with a new Turkish leader. For Kilicdaroglu, the unpredictable Kremlin is a much less attractive partner than the West.

How an isolated Russia will respond to external shocks

Paradoxically, sanctions against Russia appear both to be weakening the economy and helping to build “Fortress Russia.” Isolated from the global economy by sanctions and capital controls (that the government and Central Bank imposed in response to Western sanctions), Russia has barely been affected by tremors on the international financial markets. At present, oil prices remain the only discernible channel to deliver external shocks.

But new vulnerabilities are emerging, according to Yelizaveta Danilova, head of the Central Bank’s department of financial stability. In a recent report, she highlighted the following:

- A focus on the Chinese yuan and a high dependency on a limited number of corresponding banks. By May 2023, the share of trading in currency paired with the yuan was 36.1% of the total volume of exchange currency trading and 22.3% of over-the-counter trading. However, this market is illiquid, which could lead to temporary surges of volatility (for example, if exporters see a sharp decrease in revenue while transfers to currencies of friendly nations remain sluggish).

- The growing impact of sanctions on the debts of non-finance companies. So far, the situation is stable. However, the Western oil embargo and price cap on oil has led to increased logistics costs, the development of new markets, enforced import substitution and the organization of new payment channels.

- The withdrawal of foreign companies from Russia and the associated M&A deals financed by bank loans has caused an increase in the debt burden for companies and banks alike. Purchasing currency to pay for the shares will pressure the ruble.

Danilova adds that existing risks are still present. These include:

- Growing consumer debt. The share of consumer loans issued to borrowers who already have debts reached a record high of 36% at the end of last year.

- Imbalances in the property market and the mortgage market. The residential property market has seen excess supply and a decrease in demand. Thus, attempts to stimulate demand by subsidizing rates has led to a 30% discrepancy between primary and secondary housing markets.

- The “offshoring” of private savings. In total, from the start of 2022 to March 2023, the volume of private money transferred to individuals’ offshore accounts was 2.4 trillion rubles. These foreign investments could cause geopolitical risks and the outflow might lead to a reduction in the amount of deposits held by Russian banks.

- Russian banks remain vulnerable to interest rate rises.

Why the world should care

A robust banking system remains an important factor in the stability of the Russian economy. The biggest challenge right now is not sanctions, but transforming business models, “yuanization” and adapting to work with limited access to the global financial system (while maintaining an acceptable level of debt).

Signals

Secondary sanctions from Europe?

The EU is considering imposing sanctions on eight Chinese companies, reported The Wall Street Journal. These companies are supplying Russia with microelectronics, including semiconductors, which can be used by the defense sector. The WSJ identified the following four companies: China’s 3HC Semiconductors; Hong Kong’s King-Pai Technology HK (in March 2022 this was sanctioned by the U.S. for selling foreign goods “to numerous organizations within the Russian defense sector”); Sinno Electronics (on the U.S. sanctions list since 2022); and Hong Kong’s Asia Pacific Links (reportedly one of the main suppliers of the microelectronics used in the construction of Russia’s Orlan-10 drones).

Fortum writes off €1.7 billion in Russian assets

Finland’s Fortum has decided to write off all its Russian assets, worth a total of €1.7 billion, due to loss of control following their nationalization. Fortum CEO Markus Rauramo described Russia’s actions as an enforced takeover under the guise of concerns about energy security. In late April, the Kremlin published a presidential decree allowing the state to seize the Russian assets of any company from an “unfriendly” nation in response to the real or threatened nationalization of Russian assets abroad. Among the assets immediately placed under the control of Russia’s Federal Property Management Agency were 98.2% of the shares in Fortum, which operated Russia’s TGK-10 power generation company. Fortum’s assets will now be managed by groups linked to oil giant Rosneft.

Key figures

Weekly inflation slowed to zero from 0.19% last week from May 3-10, 2023, according to the Ministry of Economic Development. Annual inflation slowed again to 2.32%.

Russia’s budget deficit for January through April was 3.4 trillion rubles, exceeding the annual plan, according to the Finance Ministry. Revenues were 7.782 trillion rubles, down 22% compared with the equivalent period in 2022, while expenditure increased 26% to 11.206 trillion rubles. At the same time, the Ministry said that non oil-and-gas revenues were on a positive trend, while oil-and-gas revenues were “steadily reaching a stable trajectory.”

Russians have deposits worth about $1 billion in Georgian banks, according to Business Media Georgia and Russia’s Frank Media citing a report from the National Bank of Georgia. A total of 37% of funds deposited by foreigners are Russian-owned. Two thirds of deposits made by foreigners in Georgia are held with the Bank of Georgia or TBC Bank.

The Central Bank published a report on monetary policy and updated its economic forecasts:

- GDP growth predictions for this year were raised to 0.5%-2% (previous projections had it at -1% to 1%). The forecasts for 2024 and 2025 remain unchanged at 0.5%-2.5% and 1.5%-2.5% respectively. This optimism is based on increased industrial activity. An increase in investments (counter to expectations of a slump in 2023) has been accompanied by greater use of existing production facilities. In addition, consumer sentiment is improving in most sectors.

- The inflation forecast for 2023 has been lowered to 4.5%-6.5% as the economy adjusts faster than expected.

- The projected interest rate for 2023 has been adjusted to 7.2%-8.2%. The Central Bank will debate raising rates to stabilize inflation at its next meeting.

- There was a sharp downgrade in the forecast for the current account surplus at the end of the year, from $66 billion to $47 billion.

What to watch next week

- Central Bank commentary on inflation (16-22 May)

- State Statistics Service’s preliminary assessment of GDP dynamics in the first quarter of this year (17 May)

- Weekly inflation data for May 11-15 (17 May)

Further reading

How Sanctions Have Changed Russian Economic Policy Alexandra Prokopenko dispatches new features of Russian economic policy

US Intel Leaks Highlight Russia's Limited Options in Face of Ukraine's Counteroffensive Pavel Luzin examines Russian perspectives in a coming counteroffensive

Russia’s war propaganda spectrum Jade McGlynn highlights how the Kremlin’s propaganda strategy is not aiming to create a country of active war supporters

Why Did Central Asia’s Leaders Agree to Attend Moscow’s Military Parade? Temur Umarov explains why the political elites of Central Asia will continue to show loyalty to Putin

The author of this newsletter is one of Russia’s leading writers on this topic: independent economic analyst Alexandra Prokopenko. Alexandra worked as an advisor at Russia’s Central Bank and Moscow’s Higher School of Economics from 2017 to 2022 — and before that she was an economic journalist for Vedomosti, then Russia’s leading business newspaper. Today, Alexandra is a columnist at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a visiting fellow a the Center for Order and Governance in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia at the German Council on Foreign Relations. She holds an MA in Sociology from the University of Manchester.