Meet the Russian soldier whose online chats gave away military secrets

Hello! This week our main story is a scoop about the Russian soldier who unwittingly provided international investigators with key evidence about the downing of Flight MH17 over Eastern Ukraine in 2014. We also take a look at how the growing reserves in Russia’s significant wealth funds could be spent, and some of the highlights from Putin’s annual televised call-in show.

SCOOP: Meet the Russian soldier whose online chats gave away military secrets

What happened

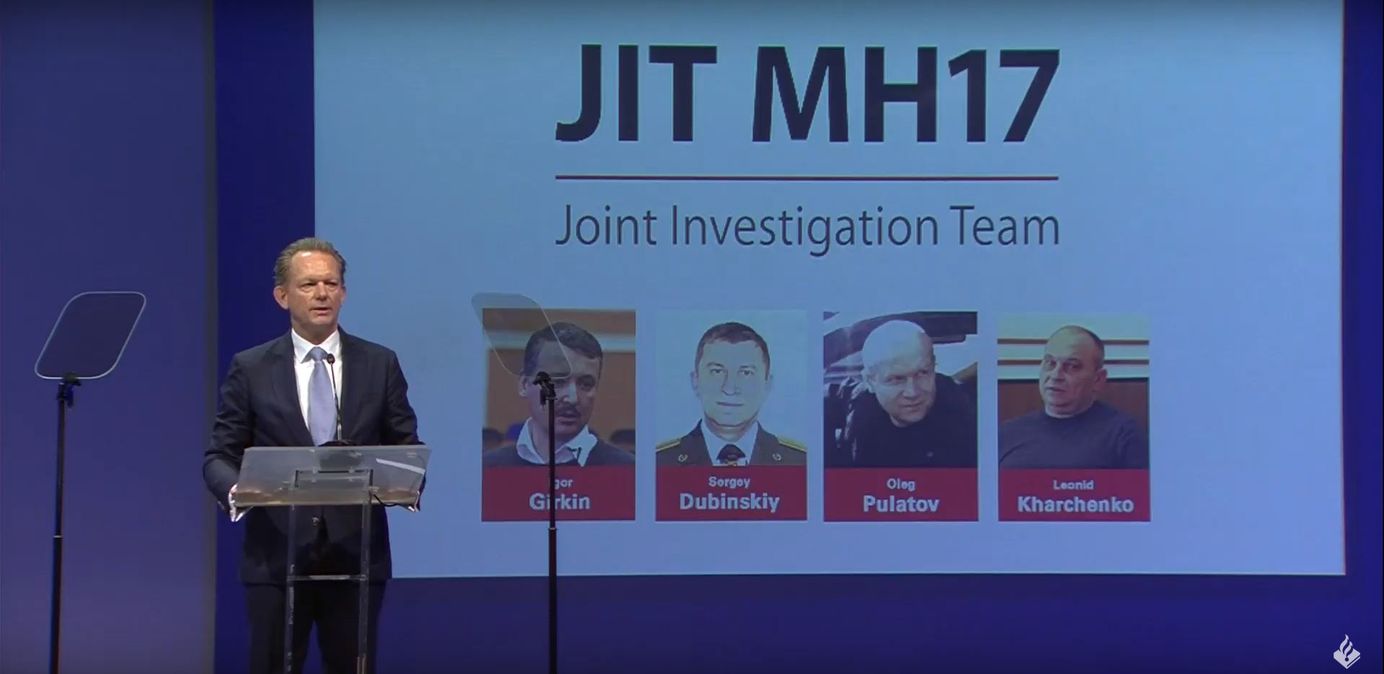

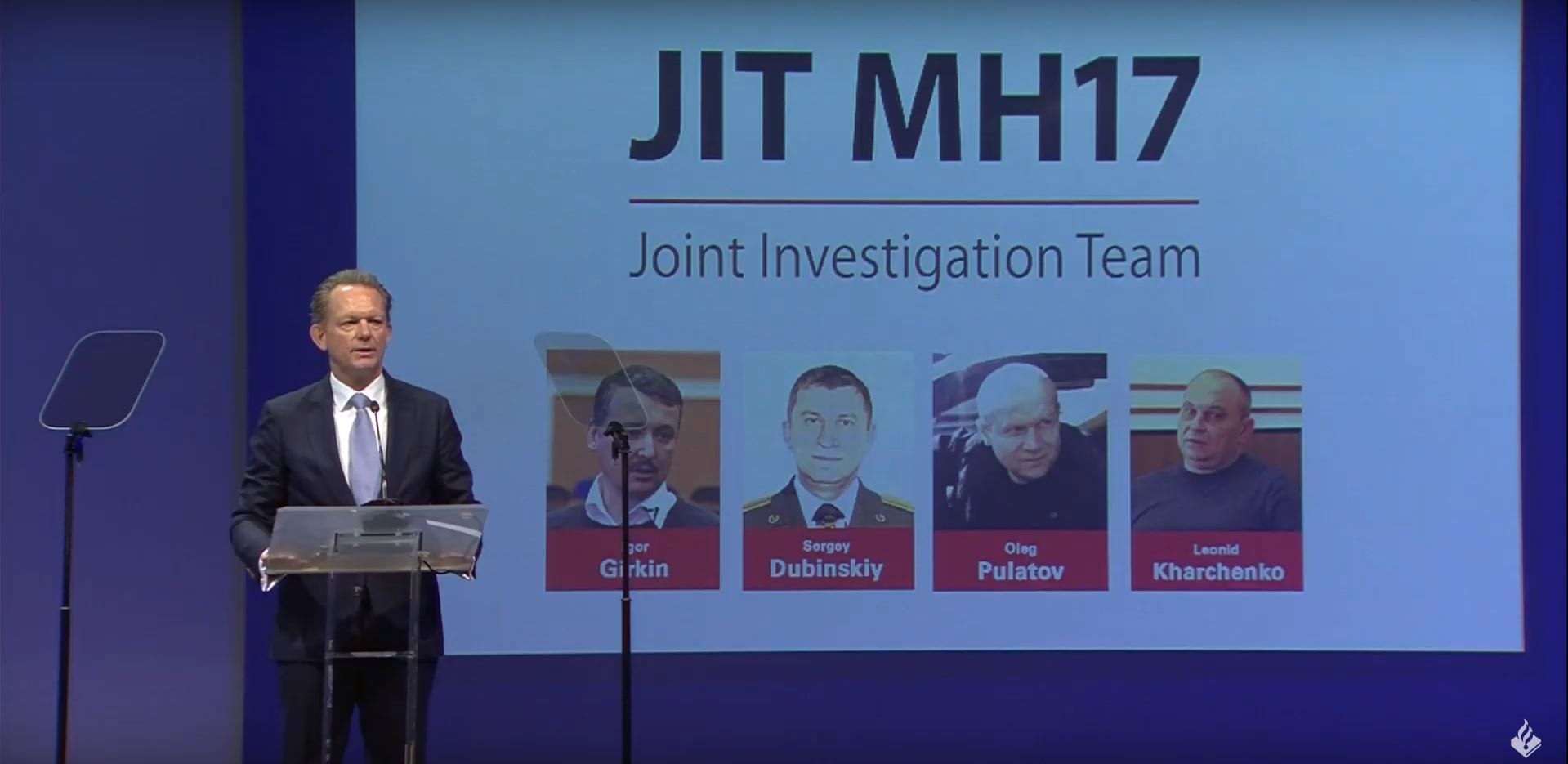

The international Joint Investigation Team (JIT) conducting a criminal investigation into the downing of the Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 over Eastern Ukraine in 2014 has named four suspects. None of them are current members of the Russian military, but JIT head Fred Westerbeke announced that there is now enough evidence to implicate Russia. The Bell located the Russian soldier whose chats helped the JIT prove it was a Russian missile system that shot down the plane. The identity of the person with whom he was communicating with is unclear, but some are speculating it was a member of a European intelligence agency.

- One piece of evidence produced to prove the presence of a Russian-installed Buk missile system in Ukraine in July 2014 was online chat records between a conscript soldier from the 2nd battalion of the 53rd anti-aircraft missile brigade (in JIT’s publication he is named “M…”) and a so-called Anastasia Dorokhova. In response to the young woman’s questions, the soldier discloses the number of his battalion and hints that a neighboring battalion of contract soldiers, was sent to Ukraine at the end of June 2014.

- In the version presented by the JIT, the Buk missile system that shot down flight MH-17 belonged to the 53rd battalion.

- The Bell, using data from the investigation, found (Rus) the social media accounts of Anastasia Dorokhova and the soldier in question, whose name is Maxim Gerasimov. In the summer of 2014, Gerasimov was serving in the 53rd brigade and based in the southern Russian city of Kursk. Dorokhova’s profile is clearly fake: her photos are used by many different social media accounts and her profile page was only updated between April and August 2015. There is no proof, but one explanation is that the account was created by a foreign intelligence agency to chat with the soldier.

- In response to The Bell’s questions via social media, the soldier blocked our correspondent, but he spoke (Rus) with Open Media, telling them he didn’t reveal anything secret to Dorokhova, but that he can’t prove this because he subsequently deleted the chat.

- The chat itself is worth reading: the naivety of a Russian soldier, who casually tells an unfamiliar young woman a dangerous secret, is striking. Dorokhova is very direct, and she asks about where he is serving, and about the mood among other soldiers.

An important detail

- Most of the evidence about Russia’s military presence in Ukraine in 2014, in particular the information about transportation of the Buk linked to MH17, was gathered from the social media accounts of participants and witnesses.

- Russia’s military leaders only recently realized the danger of smartphones in the hands of ordinary soldiers. The first news of restrictions on smartphones in the military appeared in February 2017, and a total ban came into force in March 2019. In areas of real combat operations, like the Russian airbase in Syria, measures to control smartphone use were put into place before the official ban:

Russian airbase in Hmeimim, Syria. 2018. The sign reads: Measures for information security”

Why the world should care

This new evidence will not change the view most people hold that MH17 was downed accidentally on the command of rebel field commanders in Eastern Ukraine who were given a Buk by the Russian army. New sanctions as a result of the JIT’s conclusions, are not expected any before 2021, when the trial ends, but they may be awkward for the Kremlin if they do come.

Russia is set to spend up to $60bln a year from its sovereign wealth fund

What happened

High oil prices have allowed Russia to set aside reserves equal to about 7% of GDP in just three years. From 2020, under Russian law, excess reserves may be spent — and the government is already quarreling over what to do with these tens of billions of dollars.

- By the end of 2019, the National Wealth Fund (NWF), which Russia uses to collect excess revenues from oil sales, will have reserves exceeding 7% of GDP (about $120 billion). Under Russian law, any funds raised above this amount may be spent. In 2019, the fund will have a surplus of $30 billion, and in 2020 it is forecast to reach $60 billion.

- Since 2017, any funds the state has received from oil sales at prices higher than $40 per barrel have been sent to the NWF (the figure is currently $41.60 as it is indexed on an annual basis). According to the latest forecast by the EIA, the average Brent price in 2019 is expected to be $67 per barrel.

- The Russian fund of $120 billion is far from being the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund: to make the top ten you need more than $300 billion. But is a significant sum, and in the 2007-2008 financial crisis, reserves of $120 billion were enough to shield the country from some of the economic shock.

- The NWF mainly invests in Western assets, but at least some of the surplus must be spent in Russia — likely on major infrastructure projects put forward by Putin after the 2018 presidential election. Russian economic officials don’t like this idea, arguing that some of the funds will be stolen, and that investing in Russia will drive up inflation. But the alternatives are worse. “The money could be spent ineffectively, but better to use it to build roads or bridges than to spend it supporting Syria or Venezuela,” a senior official told newspaper Vedomosti, recalling how, in December 2013, Moscow gave $3 billion from the NWF to Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich, who was toppled in a revolution just three months later.

Why the world should care

This is yet another reminder that, despite sanctions, the Russian economy is run by professionals and is far from being in disastrous shape. If oil prices fall badly (for example, if U.S.-China relations worsen), Russia has a solid safety cushion in place.

Putin’s annual televised call-in show generates less and less interest

What happened

President Vladimir Putin hosted Thursday his 17th call-in show: for more than four hours, he answered questions on live television. The viewing figures for the event, at least in Moscow, were the 6th worst of all time, and he gave few answers of real interest. However, we have selected the most important ones. Remember it’s not just Putin’s answers that are significant, but also the questions, which are, of course, pre-selected ahead of the live broadcast.

Indifference is growing: According to data (Rus) provided by Russian firm Mediascope, the Moscow television audience for Putin’s call-in show was the lowest since 2013 (there isn’t data for Russia as a whole). Viewing figures have been declining for 4 years running: in 2015, 12.7 percent of Muscovites tuned in, falling to 8.1 percent last year and 6.8 percent this time. These numbers are not surprising: Putin’s own approval rating has dropped from 45 percent in the summer of last year to 31 percent today.

Some of the more important things that Putin said:

“Real incomes have begun to stabilize”

Take-home incomes are a painful topic for Putin because they have been falling for the last five years, and this is causing widespread anger. Putin said real income declines are stabilizing, but this isn’t true: in the first quarter of 2019, they fell 2.3 percent.

There will be no reconciliation with the West

Putin was asked whether he thought a reconciliation with the West would help the Russian economy, and he responded that there can be no talk of reconciliation as Russia did not start the disagreement and it must protect its allies, including Syria.

“People from the 90s” practically destroyed Russia. Alexei Kudrin is surprisingly one of them

Putin himself read aloud a question sent in via text message: “Where is the gang of United Russia patriots leading us?” In his response, Putin compared “responsible people” from the ruling United Russia party with the “people in charge in the 1990s who drove the country into civil war and to the verge of losing its sovereignty.” Several questions and answers later, he referred to the “economists of the 1990s” and one of the country’s leading liberal economists, former finance minister Aleksei Kudrin, who is currently head of the Audit Chamber. This is unlikely to mean Kudrin’s resignation, but it is a signal. It’s possible Putin was displeased by a recent interview Kudrin gave in which he highlighted poverty levels.

Why the world should care

The economy might not be in a terrible state, but Putin’s behavior and the declining interest in his call-in show highlights that the president’s falling approval rating is a serious problem, for which a solution has not yet been found. This means the Kremlin will have to come up with new ways of boosting Putin’s popularity. In 2014, this was one of the factors that led to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbass.