Mercenaries in Minsk

Hello! This week our top story is the detention of 32 Russian mercenaries in Belarus ahead of the country’s closely-fought presidential elections. We also have data from The Bell’s investigation into sexual harassment in the workplace, and a breakdown of Russia’s role in the activities of Wirecard, the scandal-hit, defunct German payment firm.

Russian mercenaries arrested in Belarus

The already stormy Belarusian presidential election campaign became even more dramatic Wednesday with the arrest of 32 alleged Russian mercenaries. The Belarusian authorities identified the men as employees of the notorious mercenary outfit Wagner, and it led to a diplomatic row between Minsk and Moscow. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko is currently running for a sixth consecutive term in office, and appears to be trying to use the rallying cry of ‘Russian interference’ to scare the opposition and mobilize his base. The big question is: were the mercenaries operating in Belarus with Kremlin approval?

- The 32 mercenaries were arrested overnight in a sanatorium near Minsk, and video of the detentions was shown widely on Belarusian TV. The Belarusian security services stated that the men were working for Wagner, which had deployed a total of 200 fighters in Belarus to “destabilize the situation.” All the men are facing criminal cases on terrorism charges. There was no immediate reaction from Moscow — which has never admitted the existence of Wagner — but Lukashenko said that the Russians were “denying everything to justify their dirty intentions.”

- All the presidential candidates were warned by the Belarusian Central Election Committee that the government was going to enforce strict security measures at all mass gatherings, including blocking the internet.

- Despite the scare tactics, a huge rally for leading opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya took place Thursday in Minsk. Some estimates put attendance as high as 63,000 people, making it the biggest opposition rally in Belarus for decades.

- The elections are scheduled to take place 8 August. Partly as a result of Belarus’ economic problems, partly as a result of Lukashenko’s ‘coronavirus-denial’, the incumbent president is facing an uphill battle. Independent opinion polls in June showed Lukashenko would go down to a crushing defeat in free and fair elections.

- Fabricated conspiracies and ‘foreign threats’ are one of Lukashenko’s favourite strategies in difficult times. Before the 2010 elections, he accused the opposition of preparing an armed uprising, and before the 2006 elections he announced the discovery of a conspiracy that involved men from Georgia, Ukraine, and Balkan countries who were apparently preparing to poison water supplies with dead rats.

What were the mercenaries doing in Belarus?

No one seriously believes that the Kremlin is preparing to organise a coup in Belarus, or wants to help the opposition topple Lukashenko. For Russian President Vladimir Putin, a repeat of the Ukrainian revolution of 2014 in Belarus would be extremely dangerous. But it is also undeniable that the Russian detained near Minsk previously worked for Wagner, which is directly controlled by the Kremlin. Newspaper Novaya Gazeta confirmed Thursday that at least a third of the detainees had fought for Wagner in Syria, Ukraine or Africa.

Messages appeared Wednesday on Telegram channels linked to the mercenary business that the men were mercenaries on their way to fight in Libya for a Turkish paymaster. The following day, this became the official Russian version of events: the Russian ambassador in Minsk said the men were about to fly from Minsk to Istanbul.

What is really going on?

It’s clear that Lukashenko is using the situation to help him win the elections, but it’s unclear what game the Kremlin is playing. It’s particularly odd that the mercenaries acted as if they were trying to be caught, according to Belarusian political analyst Artyom Shraibman. All the men entered Belarus using their real documents despite the notorious porousness of the Russian-Belarusian border (even tourists can cross unnoticed with little difficulty).

The Russian version seems more likely to be true, but it’s still odd. If they were transiting to Libya, it’s unclear why they were so careless. And if the Belarusian authorities knew about their mission and detained them anyway, it will cause real anger in Moscow. “Maybe there’s no complex game afoot here, just a series of failures of communication,” said Shraibman. Another theory is that Lukashenko is deliberately seeking to spoil relations with Moscow, perhaps to head off Russian pressure for deeper political integration.

Why the world should care

Even if Lukashenko wins the upcoming elections, he will be left politically weakened and vulnerable. Worsening relations with Russia may be part of his post-election planning.

The Bell looks at sexual harassment in Russian workplaces

This summer has seen a series of sexual harassment scandals in Russia, almost all of which have taken place at independent media outlets. This isn’t particularly surprising: it’s journalists who write about these problems, and who give them far more attention than ordinary Russians. The Bell decided to look at how sexual harassment is viewed in the Russian business world.

- Recruitment service SuperJob has done surveys about sexual harassment in the workplace for many years. The results are odd: in 2011, 12 percent of respondents identified sexual harassment as a serious problems, but this fell to 5 percent in 2020. Anna Rivina, the head of advocacy group Nasiliu.net (‘No to violence’) said she doens’t believe that there is less harassment now – people simply do not properly understand sexual harassment, and those that experience it are reluctant to speak out.

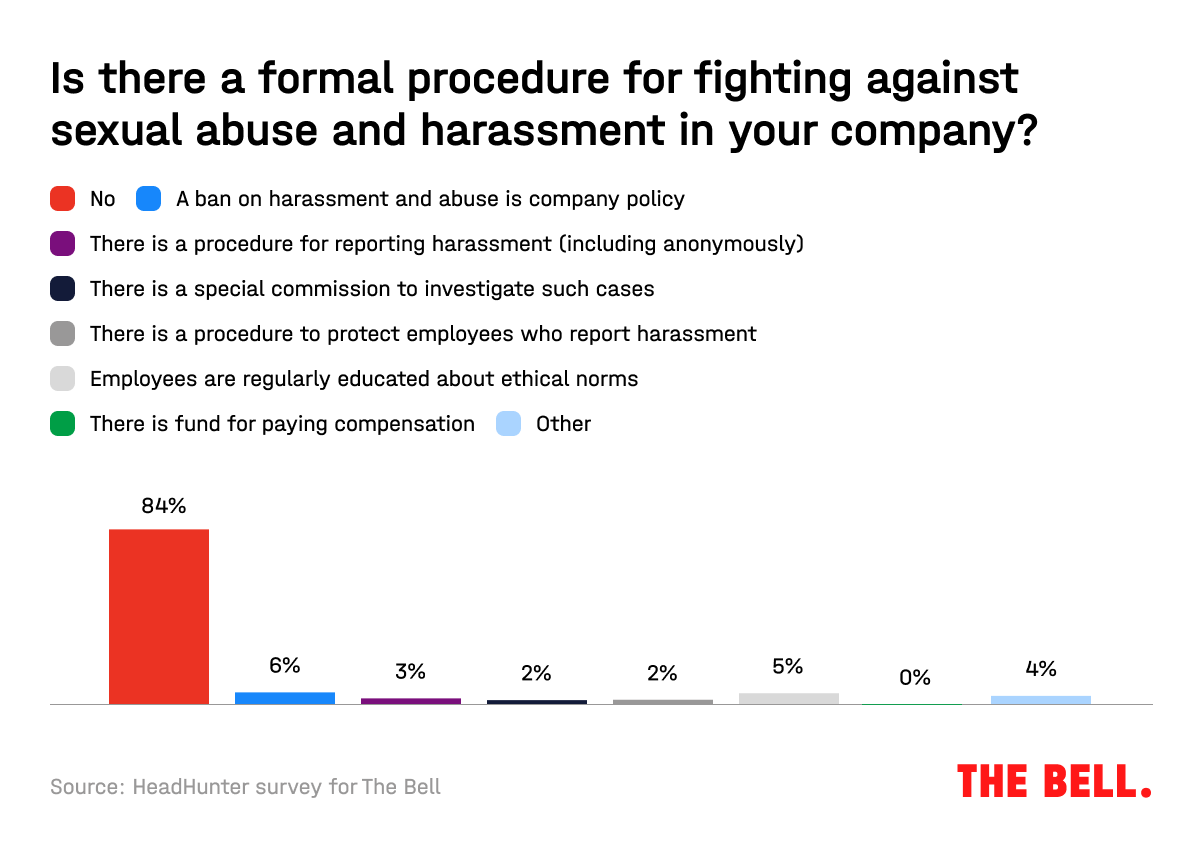

- In Russia, harassment is usually understood exclusively as sexual violence. The Bell ordered a survey from HR-firm HeadHunter that used a broader definition of harassment used by the Australian government. But the results were similar.

- One of the stories from this summer involved Russia’s biggest employer, state-owned banking giant Sberbank. So, we asked 15 of Russia’s biggest companies if they had a procedure for dealing with sexual harassment. Of the 15, only four responded: diamond miner Alrosa, steelmaker Severstal, Tinkoff Bank and internet giant Yandex (Alrosa, Tinkoff Bank and Yandex are all listed in the U.K. and the U.S.). Of these, all said harassment was unacceptable, but only Severstal named it explicitly in their ethics code.

- Even if Russian companies have global ambitions, this gives no guarantee that they are free of harassment, or take harassment seriously. One example of this is the 2015 case of Svetlana Lokhova, who worked in the London office of Sberbank’s investment banking arm and successfully sued the company for $4.6 million for sexual discrimination. She said she was referred to as “Crazy Miss Cokehead”, “Miss Bonkers”, and a “schizo nightmare” by male colleagues. Her direct boss, David Longmuir, was forced to resign.

- This sort of case is very difficult to imagine in Russia: there are no laws on sexual harassment or discrimination, and no legal precedent. Lawyers said there is only one article of the criminal code under which such prosecutions might be possible (‘Forcing an individual to have sexual relations, or other actions of a sexual character’), but it is all but impossible to use in harassment cases. Perpetrators can be punished only if they use violence, or if they violate labor laws.

Why the world should care

Despite ongoing changes at independent Russian media outlets, broader society looks unlikely to embark on a radical re-assessment of sexual harassment in the workplace. The topic will likely remain misunderstood, and largely invisible, for years to come.

What links Russia to Germany’s Wirecard scandal?

One of the main figures in the collapse of German payment firm Wirecard, chief operating officer Jan Marsalek, is reportedly hiding somewhere near Moscow. The Bell looked at Wirecard’s connections with Russia, and why Marsalek visited the country over 60 times in a decade.

- It’s perhaps no coincidence that Marsalek, who is wanted by German police, chose to seek refuge in Russia. Over the last 10 years, he has visited the country at least 60 times. He usually spent a day or less in Russia, and in 2016 he came a total of 16 times, often travelling on private jets. He went to many cities, including Moscow, St. Petersburg, Nizhny Novgorod and Kazan.

- The reason for Marsalek’s trips was a search for banks or payment services that Wirecard could buy, according to Russian friends of Marsalek who spoke to The Bell. One acquaintance said that he was aware of Marsalek holding talks with at least five different companies, apparently offering personally to take a stake. “I don’t know any dudes more cynical than him,” said another of Marsalek’s acquaintances, “the whole market understood that this was a money laundering bank and that they were laundering money from casinos, gambling and porn.”

- The banks Marsalek tried to buy included Radiotekhbank, a small bank that belonged to Robert Musin, one of the most influential financiers in the largely Muslim region of Tatarstan. A member of the ruling United Russia party, Musin owned dozens of banks until 2017 when the Central Bank withdrew a license from his main bank, Tatfondbank, and he was arrested in a $1.5 billion fraud case. All his other banks also had their licenses withdrawn. According to one of The Bell’s sources, Musin may have guessed about the coming criminal charges and wanted to use Wirecard to move money abroad.

- Owning a Russian bank may have become an objective for Wirecard after November 2017 when Russia banned all transactions with bank code 7995 (signifying gambling money). Before this, Wirecard was the main settlement bank for illegal, online casinos and bookmakers in Russia. These outfits were licensed in offshore zones, created daughter companies in Europe and, through these, connected to Wirecard, which organised the receipt of payments from Russia.

- In September 2018, Wirecard created an official daughter company in Russia, which tried to build relationships with ‘high risk’ Russian clients. But, in order for this to work, Wirecard needed its own bank. Hence, Marsalek’s search.

- At the same time as looking for a bank to acquire, Marsalek may also have been looking for an escape route. One of the executive’s acquaintances said he had been examining different countries to which he might be able to flee in the event of a sudden crisis.

Why the world should care

Western media have reported extensively on Marsalek’s possible links to Russian intelligence, which, if true, would explain why Moscow was willing to provide him a refuge. It also means public information about his whereabouts may not appear any time soon.