Mishustin feels the heat

Hello! This week our top story is about Russia’s new prime minister’s real estate holdings and how he’s using the media to try and clear up his image. We also look at the scandal over media outlet Meduza’s article accusing political prisoners of murder, a survey revealing how wealthy Russians prefer to move their money abroad, and the first interview with Kremlin ‘grey cardinal’ Vladislav Surkov since his departure from government.

Russia’s new PM seeks to save reputation via media

Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin has been in the job for 1.5 months, but discussions of his income and expensive real estate holdings refuse to die. In part, it is Mishustin and those close to him who have kept the conversation going — this week, they made a fourth attempt to use the media to answer some of the accusations. A preoccupation with his public image is one of the prime minister’s weaknesses, according to The Bell’s sources.

Mishustin has worked for the government since 1998 with only a short break in the private sector (2008-2010) when he was a partner at investment firm UFG (founded by former government minister Boris Fyodorov and U.S. banker Charles Ryan). And his relatives have never been involved in serious commercial ventures. But real estate that opposition leader Navalny found among the prime minister’s family’s holdings is valued at up to 3 billion roubles ($50 million). Some of this property was given to Mishustin’s sister by businessman Alexander Udodov, a shadowy figure who media reports identified (Rus) in 2011 as party to a tax fraud case. Mishustin was then head of the Federal Tax Service.

Mishustin has not commented on Navalny’s investigation. This is standard practice for Russian officials, and they take their lead from Putin who avoids using Navalny’s name. But Mishustin has deemed it necessary to try and exonerate himself: in just 6 weeks there have been four articles in the media that could not have appeared without his personal approval.

- January 19. Three days after Mishustin became prime minister, journalist Dmitry Butrin, who has known Mishustin for a long time, wrote an article (Rus) in Kommersant newspaper explaining Mishustin’s earnings and describing how the Mishutin family invested its money (Butrin did not cite any sources).

- February 7. A UFG managing partner published an open letter (Rus) in media outlet RBC detailing Mishustin’s work at the fund and suggesting he earned a total of $33.5 million while at UFG. But the letter led to new questions: why did a former official, Mishustin, receive a 25 percent stake in a fund managing $2 billion without making an investment? How did he earn such a commission for work that took place during the financial crash of 2008 and 2009?

- February 20. Vedomosti newspaper published an article (Rus) quoting sources from UFG and people close to Mishustin who explained that his stake in UFG was given to him by Fyodorov who “thought all partners should be equally motivated”. The size of his earnings, they said, was because Mishustin was able to attract major clients to the fund (these clients were not identified).

- February 27. In an interview (Rus) with Izvestiya newspaper, businessman Udodov said he gifted expensive apartments to Mishustin’s sister because she’s his wife. It’s unclear why this has taken almost 6 weeks to emerge.

In all likelihood, this is not the end of Mishustin deploying intermediaries to explain his wealth. Firstly, many questions remain about Mishustin and his family’s income — Udodov’s family ties don’t make his gift any less corrupt. Secondly, on the day he was appointed prime minister, Mishustin’s acquaintances told The Bell that the new prime minister is unusual for a Russian official because he cares about his public image.

Why the world should care

No one in Russia is really surprised that the family of the new prime minister owns such expensive property (everyone in the Russian elite has significant real estate holdings). But the fact that Mishustin is trying to explain himself actually speaks in his favor — a prime minister who worries about his personal PR is better than a prime minister who isn’t interested in what people in Russia and abroad think about him.

Accusations fly as political prisoners accused of murder

Russia’s most popular independent media outlet, Meduza, waded into a firestorm this week when it published an investigation into a group of men recently given huge jail sentences on dubious terrorism charges. In the article, former associates of the accused claimed they were involved in drug dealing, and had carried out a double murder. Opposition activists immediately criticized Meduza for discrediting a public campaign to free the men, alleging the journalists had been manipulated by the security services.

- The so-called Network case has been one of the most controversial criminal investigations in Russia in recent years. In 2017, the Federal Security Service (FSB) announced it had uncovered a radical leftwing organization called Network that was planning a series of terror attacks. A total of 11 people were arrested in the case, and several weapons were seized.

- Almost all of those arrested admitted guilt, but four later testified their confessions had been extracted under torture. There is little doubt this is true: signs of physical abuse on the defendants were found during medical examinations. It is also easy to believe the whole case was invented — another radical organization recently ‘uncovered’ by the FSB also bears the hallmarks of a fabrication. Despite this, seven of the accused were each given prison sentences of between 6 years and 18 years earlier this month. Court hearings for several others began this week.

- In Meduza’s controversial article, two acquaintances of the defendants said Network members had supported themselves by selling drugs. After the first arrests, the rest went on the run. Then, when two of them, Artyom Dorofeyev and Yekaterina Levchenko, decided they wanted to go home, they were shot and stabbed on the orders of the group’s leader, Dmitry Pchelintsev. The youngest member of the group, Alexey Poltavets, who later fled Russia, told Meduza he took part in the murders.

- In a special editorial published at the same time as the article, Meduza conceded the article was “one of the most difficult in their editorial history”. The authors said they were confident the Network case was fabricated, but maintained society had a right to know about the murders (which had been ignored by law enforcement).

- Meduza was hit with a flurry of criticism led by allies of opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who has repeatedly attacked independent media outlets for allegedly collaborating with the authorities. Some accused Meduza of being manipulated by the FSB, others even suggested there had been deliberate collusion.

- Critics highlighted that one the obvious problems with the article is that it does not meet journalistic standards: in places the text is highly speculative, and the journalists did not get responses from most of the people they were implicating in very serious crimes. Some noticed that the article had been put together in great haste (Meduza’s journalists first found out about the murder accusations on 14 February and published just 7 days later). It also emerged that Meduza’s sources had previously shared their version of events with other independent media outlets, which declined to publish anything, in part because these sources changed their story several times. Finally, the article went live at 8:30pm on Friday: important investigations like this are very rarely released at such a ‘dead time’ for online news.

- Those of a more conspiratorial mindset pointed out that the remaining defendants in the Network case were due to go on trial the day after publication, and that the FSB likely wanted to discredit them ahead of the hearing. Predictably, the Meduza article was widely referenced by state-owned television networks.

Why the world should care

Meduza is a genuinely independent media outlet, and The Bell is certain there was no deliberate collusion with the FSB. After enduring several days of criticism, Meduza had to explain it had rushed to publish because its journalists knew the relatives of the two victims were about to go public. This seems the most plausible explanation: sometimes journalistic instinct wins out over ethics and standards when it comes to being first with a story.

Disclaimer: The Bell’s founder, Elizaveta Osetinskaya, is a member of Meduza’s board of directors, and the author of this article is acquainted with many Meduza journalists

Where do Russia’s wealthy keep their money?

The richest men and women in Russia prefer to invest in bonds, have begun paying more taxes in Russia and are looking to extract assets from Cyprus and Latvia, according to a survey (Rus) published Thursday by Ernst & Young and international real estate broker Tranio. We gathered some of the most interesting findings.

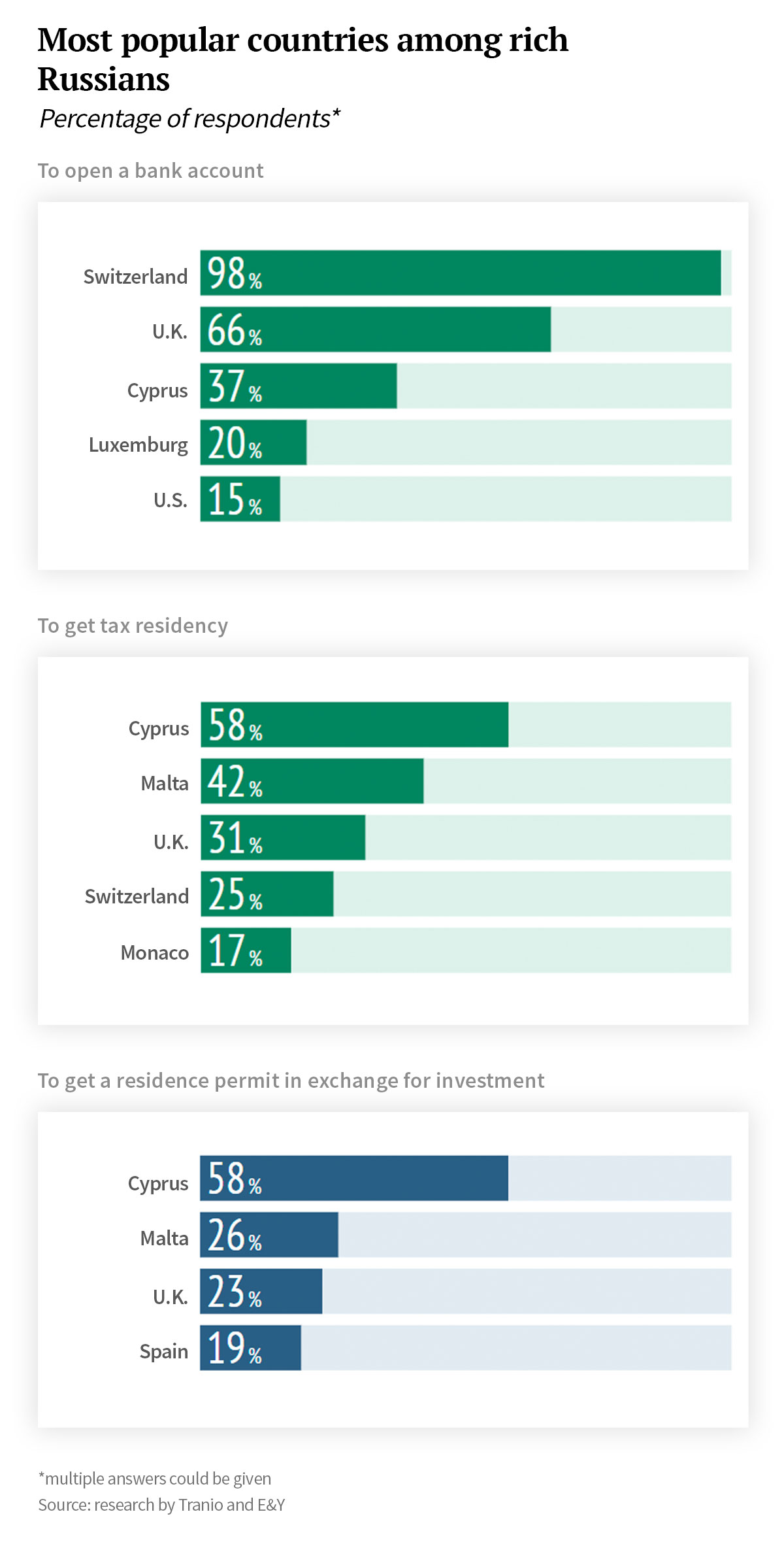

- Traditionally, Cyprus and Latvia have been havens for Russian money, but the survey showed that this is less and less the case. Almost 40 percent of respondents said they were looking to move their money out of Cyprus, while 30 percent said the same about the Baltic countries (this mostly concerns Latvia). In recent years, Cyprus has introduced more stringent financial accountability rules, while Latvia has been rocked by huge money laundering scandals that have led to greater scrutiny.

- But this does not mean that Russia’s wealthy have severed all ties with Latvia and Cyprus. Far from it. The financial relationship with Cyprus, in particular, remains strong with the survey showing Cyprus was the third most popular choice for deposits (37 percent), and the most desirable place for tax residency (58 percent).

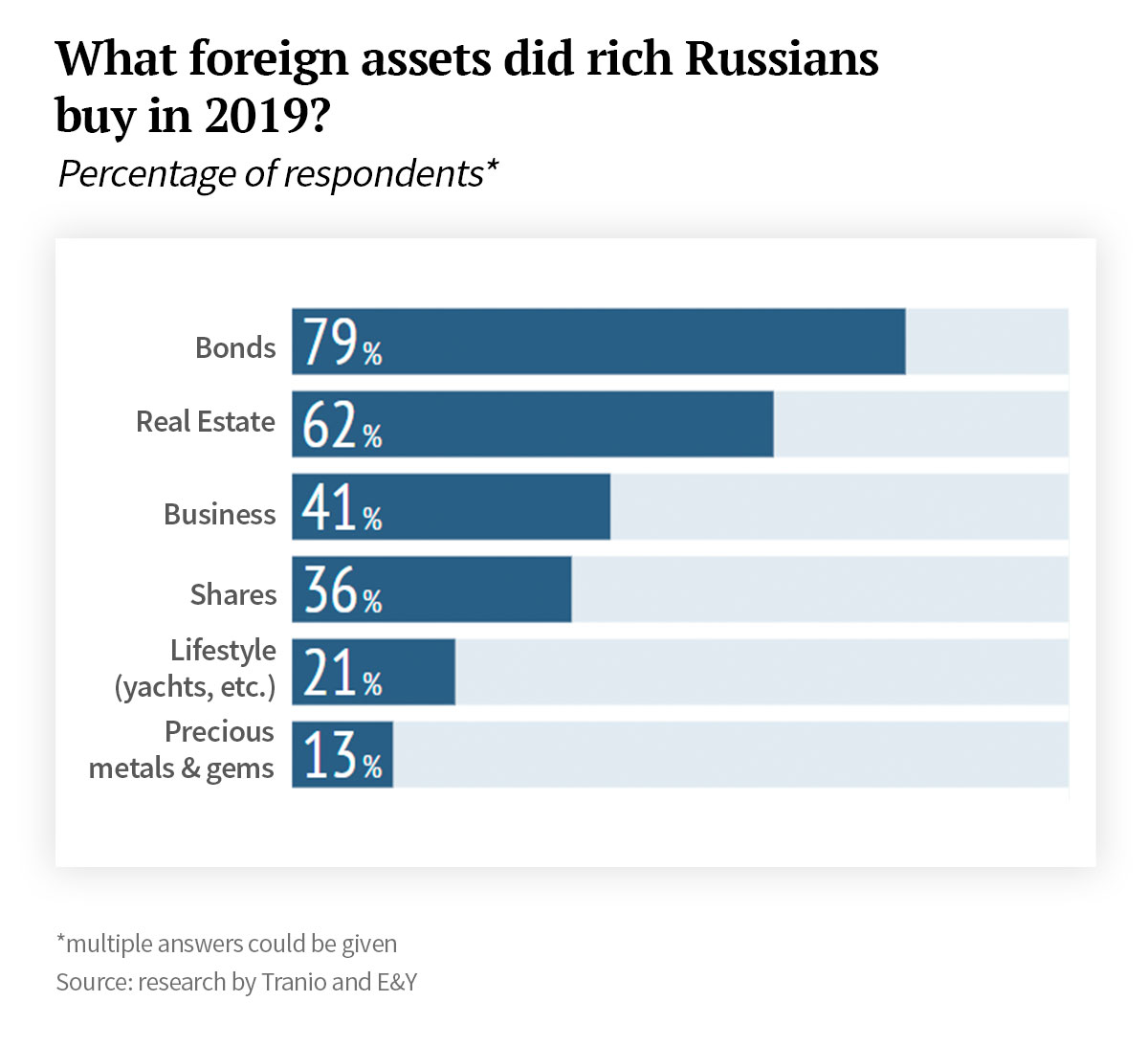

- The most popular assets with Russians investing abroad are bonds (79 percent), followed by real estate (62 percent), business (41 percent), shares (36 percent) and elite property, yachts and antiques (21 percent).

- Other trends identified by the research include that more Russians are informing the Russian tax service about their bank accounts abroad (up from 42 percent in 2017 to 70 percent in 2019); that taking foreign citizenship to hide from the tax authorities is a more popular option; and that the use of nominal owners is becoming less frequent.

- Aside from Cyprus and Latvia, the other most in-demand destinations for Russian money are Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Malta. Switzerland is the most popular place to open a bank account (98 percent), followed by the U.K. (66 percent). After Cyprus, the most-favored countries to gain tax resident status are Malta (42 percent), the U.K. (31 percent), and Switzerland (25 percent).

- The survey was conducted at the end of 2019 among 44 financial and legal specialists who work with Russian high-net worth individuals. Respondents could pick several options in their replies.

Why the world should care

Western countries have tightened anti-money laundering regulations in recent years — and this survey is yet more evidence that this has had an impact on how wealthy Russians distribute their assets. At the same time, the survey reveals few dramatic changes.

Kremlin ‘grey cardinal’ speaks out after dismissal

One of the most iconic figures of Russian politics, Vladislav Surkov, gave a rare interview (Rus) Wednesday, shortly after being dismissed as a Kremlin aide. In traditionally gnomic fashion, Surkov veered between the bizarre and the provocative, and managed to reveal little about what he will do after his 20 years of government service.

- Surkov, 55, is most well-known for his role in the creation of Russia’s current political system as deputy presidential chief of staff between 1999 and 2011. Since 2013, he has been an aide to Putin, overseeing Kremlin policy in Ukraine and managing the Russian-backed separatist governments in the breakaway Donbas region.

- The recent interview appeared on an obscure site called Actual Commentaries, and was conducted by political expert Aleksei Chesnakov who operates as an unofficial spokesman for Surkov.

- In his answers, Surkov did not give a reason for his dismissal, but said the “context had changed” regarding Ukraine, and that the decision was entirely his own. There has been speculation that the appointment of former deputy prime minister Dmitry Kozak as his replacement may mean Russia will take a less hardline approach in Ukraine, opening the way to a negotiated settlement with Kyiv. Surkov denied Ukraine was a real state, and said he thought it unlikely Ukraine’s breakaway eastern territories could ever be ruled from Kyiv. “Donbas doesn’t deserve such humiliation. Ukraine doesn’t deserve such an honor,” he said.

- Author of the term ‘sovereign democracy’ to describe Russia under Putin, Surkov also took the opportunity to reaffirm his loyalty to the Russian leader. He described himself as a “Putinist”, and said the constitutional changes currently under discussion meant Putin could stay on for another two presidential terms after 2024.

- But Surkov reserved his most deliberately bafflingly remarks for his career plans, which he said would be outside government. “I find it interesting to work in the genre of counter-realism. In other words, when… you need to act against reality, change it, re-cast it,” he said. “Routinization… doesn’t demand anything new from you. Only to repeat yourself. Why do this? Let others repeat after me.”

Why the world should care

The departure of Surkov from the world of officialdom is a watershed moment for Russian politics. Though out of office, he remains a powerful figure whose next moves will be watched very closely.