Moscow doesn’t like the Ukraine grain deal, but won’t ditch it

Hello! This is Alexandra Prokopenko with your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. In this newsletter we focus on disputes over the Black Sea grain deal and why it’s almost certain that Moscow will agree to another extension. We also compare NATO and Russian defense spending and look at what the Central Bank has identified as a cyclical peak in the Russian economy.

Russia is too dependent on China and Turkey to back out of the grain deal

The Kremlin may be unhappy with both the implementation of the Ukraine grain deal and perceived slights from Turkish President Recep Erdogan, but Russia is still likely to extend the deal for a fourth time. Moscow’s grumbles are already a traditional feature of the build-up to the latest extension deadline, with the result that, this time, world grain prices (usually highly volatile) barely flickered as the Kremlin issued threats to back out. The deal’s guarantor, and one of its biggest beneficiaries, is Turkey. The main buyer of grain is China. Both countries are now key trade partners for Russia — and Russia’s dependence on these partners is now so great that its hands are tied.

What’s the deal?

A year ago in Istanbul, Russia and Ukraine signed an agreement brokered by Turkey and the United Nations. As a result, Kyiv was allowed to continue exporting grain via its Black Sea ports and Western sanctions on Russian agricultural products and fertilizers were relaxed. The Kremlin pledged not to attack grain ships in the Black Sea, while Turkey and the UN were to carefully check that vessels were not being used to transfer military supplies. The U.S. and European Union introduced exemptions to their sanctions on Russia, and the developing world breathed a sigh of relief as grain prices stabilized.

How does it work?

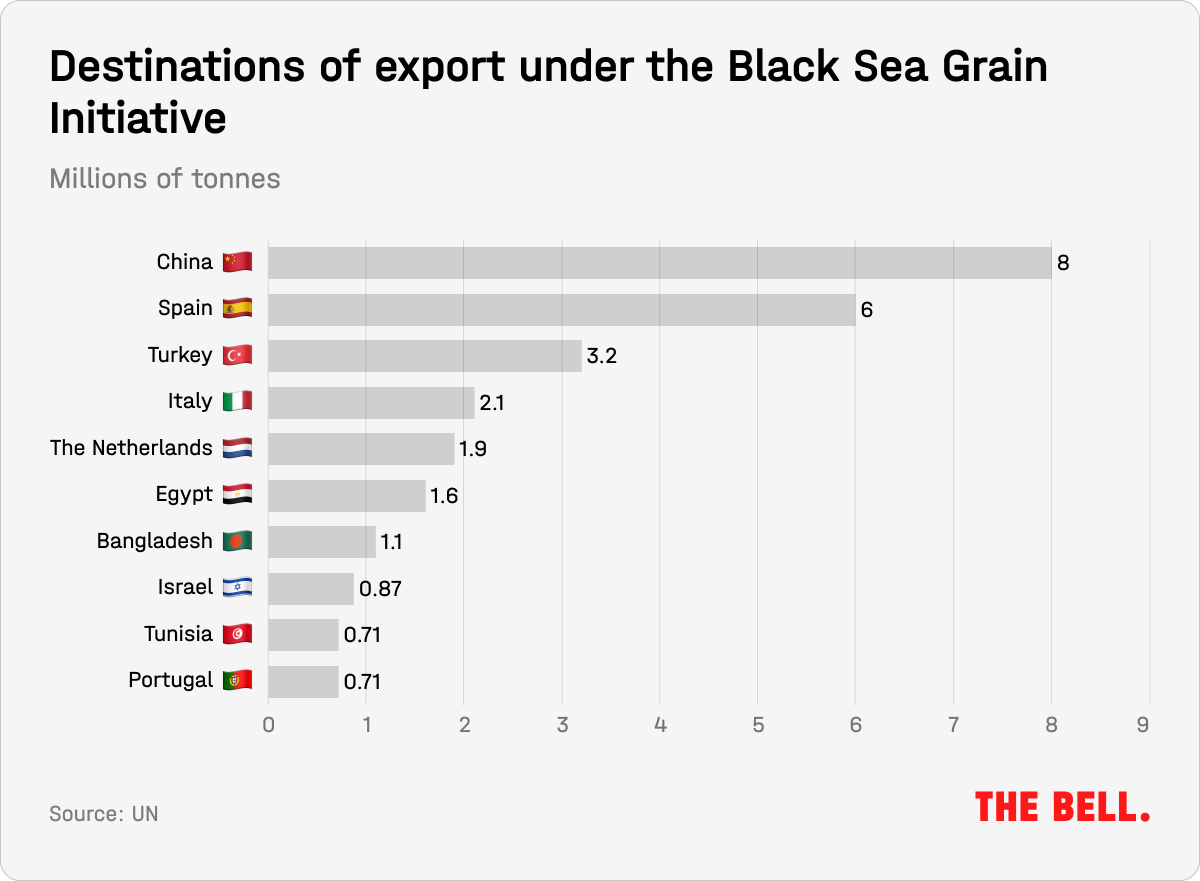

About 33,2 million tons of grain worth roughly $8-9 billion have been exported from Black Sea ports over the last year, according to Andrei Sizov of the SovEcon analytical center. China is the biggest buyer (8 million tons) followed by Spain and Turkey, according to UN figures.

Ukraine’s Black Sea ports are not the only export path for the country’s grain. Ukraine also dispatches grain from river ports on the Danube and sends it by rail to Romania, where it is transferred to sea-going vessels. However, thanks to the deal with Russia, grain shipped from Ukraine’s Black Sea ports accounts for the majority of exports.

For Kyiv, the grain deal is more than just a source of foreign currency. It empties the country’s granaries ahead of the new harvest and eases internal pressure on prices. The deal is also driving down global grain prices and makes food more affordable for the developing world. “Prices have been falling over the past year since May, especially once it became clear that Russian and Ukrainian grain remained on the market,” said Sizov.

Russia’s objections

There’s nothing new about Russia’s complaints. The Kremlin was unhappy with the deal within a few weeks of it coming into force but the complaints got particularly loud during Ukraine’s successful counteroffensive in Sept. 2022. In particular, Moscow maintained that grain was not going to the world’s poorest countries (even though no export routes had been specified as part of the deal). In reality, the Kremlin was seeking to remove barriers to Russia’s grain and fertilizer exports, and unblock the Tolyatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline.

After damage to the pipeline in June, the latter demand has been dropped. However, the question of exports is more complex. Officially, both the EU and the U.S. have removed the threat of sanctions from Russia grain and, from a compliance perspective, there should be no problems with grain exports. However, despite this, Western companies are in no hurry to resume business as usual with Russian partners. There are several reasons — difficulties in settling payments, increased costs and the risk of new sanctions in the event of a military escalation. In addition, most major Russian agricultural companies are somehow connected to the state, or have sanctioned individuals among their senior management. The UN has no influence on corporate decisions and, while the war in Ukraine continues, Russian companies will remain “toxic” for the Western financial system.

These problems did not stop Russia from recording a bumper agricultural year, supplying 60 million tons of grain to international markets between July 2022 and July 2023 for which it earned $41 billion. Forecasts for the new harvest are similar: Russia has a record grain surplus and exporters have adapted to the restrictions. The occupied territories of Ukraine are now active players on the grain markets, with Russian security forces involved in grain collection. “Exports are breaking records and will continue to grow,” Sizov said.

Another Russian demand is to reconnect state-owned Rosselkhozbank — through which export payments pass — to the international payments system SWIFT. Previously, the bank was headed by Dmitry Patrushev, son of Security Council secretary Nikolai Patrushev. Dmitry Patrushev is currently Russia’s agriculture minister.

The EU cut off Rosselkhozbank from SWIFT in the summer of 2022. Later, the European Commission explained that removal from SWIFT for Russian banks did not mean an end to a corresponding relationship with European banks. However, the UN is lobbying for a compromise: connection to a “daughter” of Rosselkhozbank, which would allow export transactions to take place. If the European Commission agrees, then Russia will have a second bank that is ring-fenced against Western sanctions (the other is Gazprombank that handles payments for energy exports). But there could be a downside: a positive decision on the Rosselkhozbank “daughter” could mean stricter sanctions on other banks.

Dependency and expectation

When it signed the Black Sea grain deal, the Kremlin did not anticipate that it would find itself so heavily dependent on Turkey and China. However, the Ukraine war and the international fallout has driven it into the arms of Beijing and Ankara.

China has become one of the main buyers of Russian energy and a key supplier of goods, including those Russia is unable to obtain elsewhere because of sanctions. From January to June, imports from China were up 78% to $52 billion and exports rose 19.4% to be worth $114.55 billion. For the first time ever, Russia was one of China’s top five trading partners.

The trade figures with Turkey are also striking: from January to June, exports from Turkey to Russia doubled compared with the same period last year (they are now worth almost $5 billion). In turn, Russia supplied $27.7 billion worth of goods to Turkey. For Moscow, Ankara is not just a valuable logistics hub and a “window to Europe” for traveling Russians. It’s also one of the few countries that maintains a high-level dialog with Moscow. This is so important to Moscow that the Kremlin has turned a blind eye to the unexpected return of Azov Brigade commanders from Turkey to Ukraine, cooperation between Ankara and Kyiv in drone production and discussions about Turkey’s EU membership.

Why the world should care

In the year since the Black Sea grain deal was agreed, Russia has failed to leverage its position and has consistently underestimated the changing balance of power. While Putin initially saw the grain deal as a way to pressure Ukraine and the West, the reality is that Russia has been reduced to the status of a technical partner.

Can NATO outspend Russia on defense?

It was no surprise that the question of Ukrainian membership of NATO overshadowed the issue of defense spending at the recent summit of the military alliance in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. But this topic is becoming increasingly urgent as NATO countries try to replace the weapons and ammunition they have sent to Ukraine.

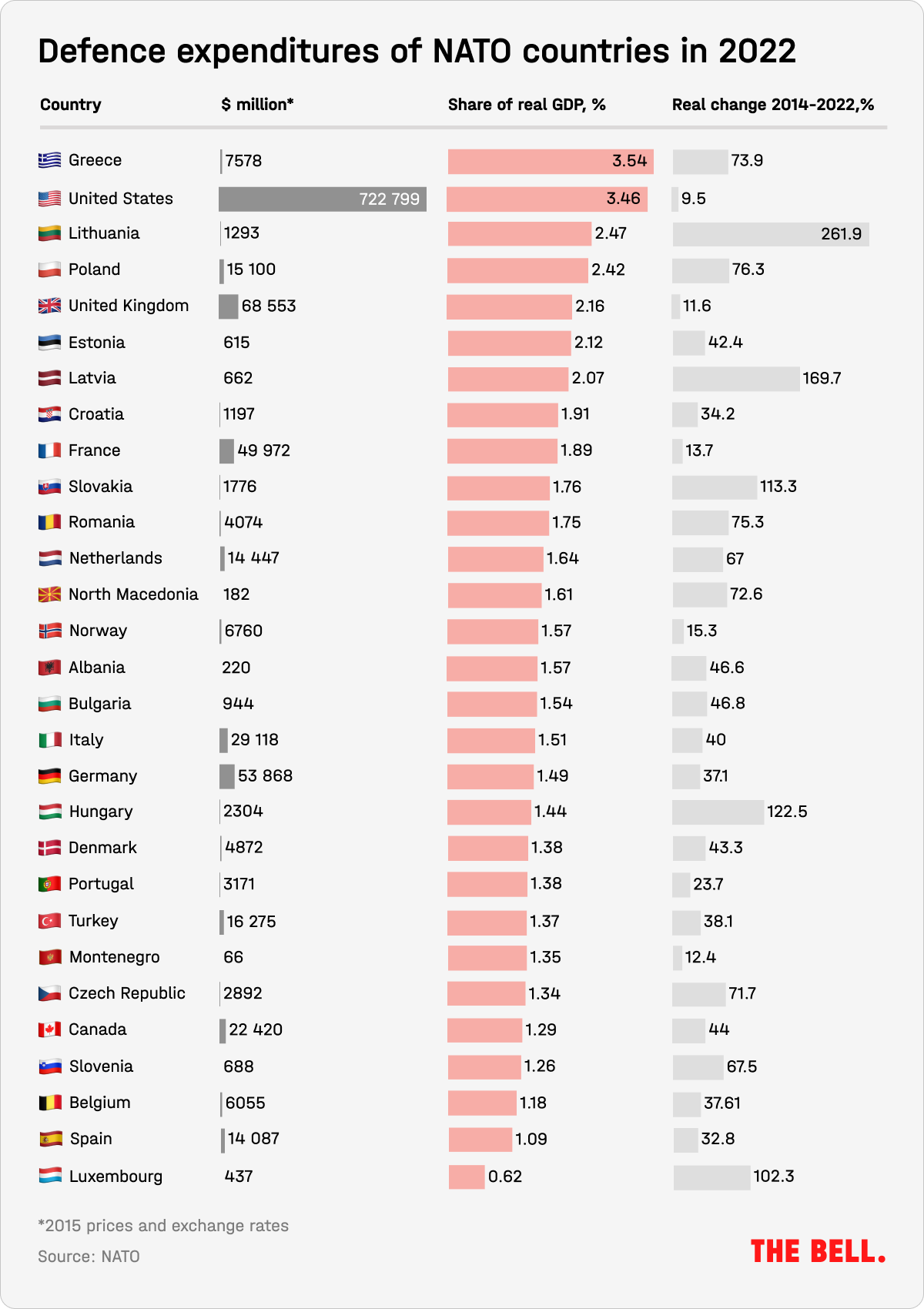

NATO members agreed in 2014 to increase defense spending to 2% of national GDP within a decade. So far, this has not happened. Europe is in no hurry to spend more. Last year, the final communique from the NATO summit in Brussels stated that only 10 member states were set to reach this annual target. In reality, seven of them cleared the threshold: U.S., Britain, Greece, Poland and the three Baltic states. The other big economies in the alliance — Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Canada — spend about 1.5% of GDP on defense.

At last year’s summit, the leaders of NATO promised that, by 2024, two thirds of the alliance would reach the 2% target. That pledge disappeared from the final communique of the Vilnius summit. There was no concrete forecast or deadline in its place, merely a restatement of the 2% target and a recognition that some countries might exceed this limit due to the need to increase military equipment production.

In total, the NATO member nations that are lagging behind will need to increase defense spending by $102 billion if they are to meet the target. Most of this will have to come from Germany, Italy, Spain, Canada, Belgium and Turkey.

Put another way, if this comes to pass, NATO countries will be increasing their defense budgets by twice the amount of Russia’s total projected military spending for 2023. Even allowing for the difference in purchasing power, it’s unlikely Russia could increase its defense spending to keep pace. An increase proportional to NATO’s plans would require Moscow to implement a 10% rise in defense spending.

Why the world should care

If NATO countries are seeking a repeat of the 1980s when the Soviet Union was economically ruined by an arms race, they have a chance of success.

Russian economy approaches cyclical peak

The Russian economy is close to a cyclical peak and by some measures — such as consumer demand — it has already passed it, according to Central Bank analysts. In particular, they argue, a growth in budget spending and lending has pushed demand beyond an equilibrium. Supply of goods and services is lagging behind demand, despite fast growth (0.7% quarter-on-quarter). And this is aggravating production difficulties — a tight labor market and capacity limits — which drives up prices.

It is not an even picture across the economy. Industries reliant on state contracts and domestic demand (such as tourism) are growing at record speed. However, the automotive and timber industries, along with aviation, are far from recovery. Generally, businesses are managing to maintain their current output. At the same time, resource-intensive and technically complex projects have been delayed. The challenges posed by tech sanctions are not serious for the moment, but will get bigger over time. Another challenge for the economy, as noted by the Central Bank analysts, is the risk of disruption to cross-border supply chains, including tech ones, in the event of secondary sanctions.

Key figures

June saw Russia’s current account balance dip into the red for the first time since the summer of 2020, according to the Central Bank. The monthly deficit was $1.4 billion. As a result, the current account surplus for the first half of 2023 was $20.2 billion, compared with $147.6 billion for the first half of 2022. The main reasons were a reduction in the balance of trade and dividend payments.

Russians spent 6.2 billion rubles on foreign currency purchases during Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin’s abortive rebellion in June, according to Central Bank calculations. The demand for currency last month was driven by banks and big businesses: since the start of June, large buyers have accounted for 40% of purchases, up from 10% the previous month. The share of the top five largest players on the market at least doubled, which further hit the exchange rate. Russia’s currency fell 10.4% against the U.S. dollar in June.

In the week of July 4-10, inflation in Russia increased slightly from 0.13% to 0.14%, the Economic Development Ministry reported. Annual inflation increased from 3.43% to 3.59%. Inflation in June 2023 was 0.37%, compared with 0.31% in May.

Analysts surveyed by the Central Bank in July raised their forecasts for inflation, GDP, interest rates and the exchange rate for this year.

The volume of interbank loans on the balance sheets of Chinese banks’ Russian subsidiaries has increased significantly between Feb. 1 2022 and June 1 2023, media outlet RBC calculated from data published on the Central Bank’s website.

- The Russian subsidiary of Bank of China increased the volume of such loans by 107 billion rubles. Before the invasion of Ukraine, interbank loans made up 8.2% of the bank’s assets. Now that figure has almost doubled to 16.3%;

- The Russian subsidiary of China Construction Bank saw the volume of its interbank loans increase almost sixfold to 15.9 billion rubles. On Feb. 1 2022, these loans made up 14.9% of the bank’s assets, but on July 1 2023 it was 26.2%;

- ICBC, which is owned by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited, increased the volume of its interbank loans 3.3 times to 9.7 billion rubles.

What to watch in the coming week

- The Central Bank’s interest rate meeting (July 21)

- Producer price index for June (July 19)

- Weekly inflation data (July 19)

Further reading

Sergey Vakulenko looks into the future of Russian oil sector

Is Russia About to Add Ideology to Its Chinese Imports? Mikhail Korostikov on the Chinese influence on Russia’s elite

Russia and the Long Shadow of Versailles Barry Eichengreen weighs the choice between using Russian frozen assets to finance Ukraine's reconstruction and imposing ongoing reparations payments

The author of this newsletter is one of Russia’s leading writers on this topic: independent economic analyst Alexandra Prokopenko. Alexandra worked as an advisor at Russia’s Central Bank and Moscow’s Higher School of Economics from 2017 to 2022 — and before that she was an economic journalist for Vedomosti, then Russia’s leading business newspaper. Today, Alexandra works as a researcher at Center for East and European Studies (ZOiS) in Berlin a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a visiting fellow a the Center for Order and Governance in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia at the German Council on Foreign Relations. She holds an MA in Sociology from the University of Manchester.