Central Bank warns Russian economy running on borrowed time

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. This week we focus on the Central Bank’s decision to raise interest rates to within a percentage point of an all-time record, and how President Vladimir Putin’s view of the economy is increasingly divergent from the technocratic managers in charge of it.

Nabiullina hikes rates to 16%, says Russian economy on borrowed time

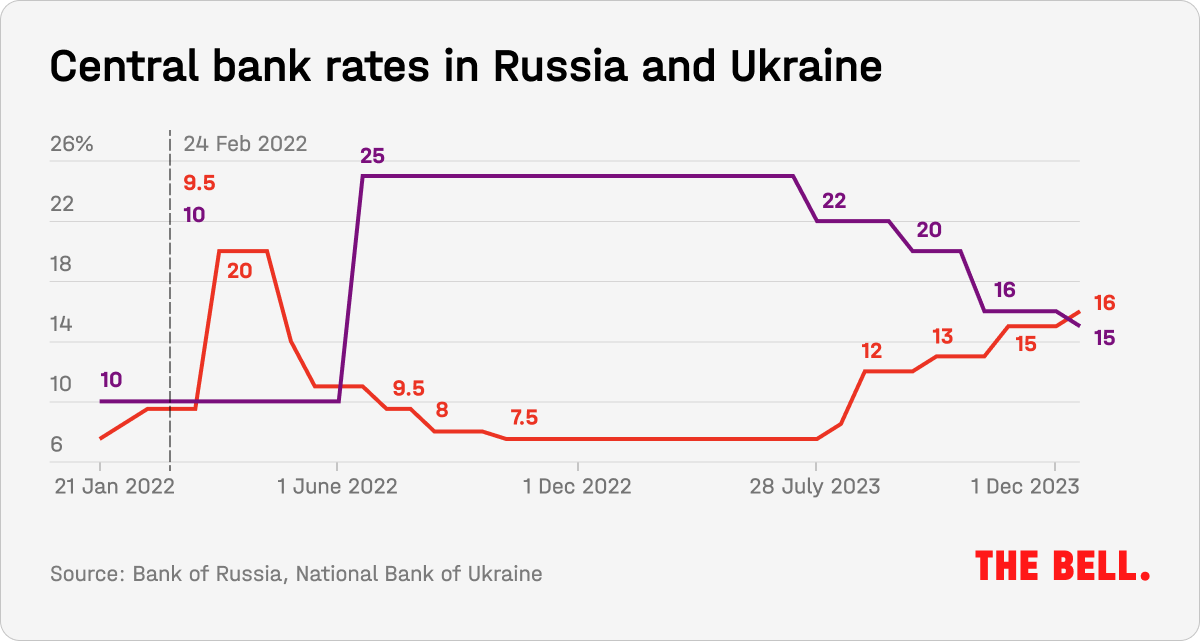

While central banks in the West are poised to begin cutting interest rates, the opposite is underway in Russia. On Friday, the Central Bank pushed rates to 16%. In a press conference, Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina likened the Russian economy to a car trying to drive too fast. “It can go, it might even be quick, but not for long,” she warned.

How the Central Bank sees the economy

The decision of the Central Bank’s board was fully in line with expectations. Rates are now within just one percentage point of the all-time record of 17%, which was hit after the collapse of the ruble in late 2014. The bank began its current policy tightening in July and, over the course of the subsequent five months, has raised rates by a total of 8.5 percentage points. Russia’s interest rates are currently even higher than in Ukraine.

When the Central Bank hiked rates in both 2014-2015, and in early 2022 after the invasion of Ukraine, it was quick to bring them down again once the immediate crisis had passed. This time, however, high rates are here to stay, Nabiullina told journalists Friday. She emphasized that the current high inflation is a systemic problem – and not linked to exchange rate fluctuation, or other one-off factors.

By the end of the year, inflation in Russia will be at least 7.5%, which is at the upper end of the Central Bank’s projected range. According to Putin, it might even be “closer to 8%.” For the past four months, core inflation has been growing over 10% in annualized terms, Nabiullina said. She gave the service sector as an example – despite only being slightly affected by the exchange rate and other one-off factors, inflation is up 14% in three months.

This is all explained by an overheating economy unable to meet rising demand. And the latest figures suggest GDP growth is causing even more of an imbalance than the Central Bank had anticipated. “Think of the economy as an automobile,” Nabiullina said. “If we try to drive it faster than it can go, and pump the gas as hard as we can, sooner or later the engine will burn out and we won’t get far. We can go, maybe even quickly, but not for long.”

The other main points Nabiullina made were:

- Inflationary pressure remains high, but will likely slow next year (peak inflation is expected in the spring). The Central Bank believes that, by the end of 2024, it can bring inflation down to 4%.

- GDP growth in the third quarter of this year (officially 5.5%) is higher than expected. To support growth at this level, the economy is consuming resources at almost full capacity. Such growth will not last long, but the Central Bank does not anticipate a recession. Its current prediction for next year is between 1% and 1.5% GDP growth.

- Unemployment reached a new record low of 2.9% in November. Companies are increasingly looking to maximize staff productivity, and the manufacturing sector is ever more frequently looking to extend the working day, or add extra shifts.

- State subsidized lending, particularly subsidized mortgages, continue to fuel inflation and distort the influence the Central Bank’s interest rate changes have on the market. Last month, 80% of new mortgages were subsidized.

- The cooling global economy is leading to reduced demand for raw materials. As a result, Russian oil and gas exports are falling.

Unsurprisingly, there was no discussion of the reason for Russia’s overheating economy at Nabiullina’s press conference. The reason, of course, remains the war in Ukraine – and Russia’s massive increase in military spending (up 68% next year).

How Putin sees the economy

The day before the Central Bank announced it was hiking interest rates, Putin spent four-and-a-half hours answering questions from journalists and the public. It was a combination of two annual presidential events (both canceled last year because of the war): a big press conference and a televised Q&A session. And it was an opportunity for Putin to be seen ahead of presidential elections scheduled for March.

The key message was confidence that Russia will defeat Ukraine on the battlefield, while everything at home remains stable. The economic data that so alarms Nabiullina was perfect for this purpose: Putin used the same figures, but he gave them a positive spin:

- Economic growth of 5.5% in the third quarter of this year means Russia has reversed last year’s contraction. “It’s a good indication,” Putin said.

- By the end of the year, Putin said he expected inflation to be as high as 8%. “Unfortunately, we have rising inflation,” he admitted. But he assured viewers that the Central Bank and the government were taking necessary measures, and that inflation is expected to return to target levels.

- Industrial output is growing (at 3.6%), “I’m especially pleased” with 7.5% growth in manufacturing, Putin said (this figure reflects Russia’s booming defense industry).

- Salaries are up 8%, disposable incomes are up 5%, and unemployment is at an all-time low of 2.9%. “This is a very good integrated indication of the health of the economy,” Putin said.

As always, Putin’s speech relied on manipulations of the facts, omissions, and a few outright lies — you can read more about this here. But his optimism makes sense. The Russian economy has adapted well to the role he is demanding of it: support the war in Ukraine without damaging standards of living. This approach will inevitably have a whole raft of serious consequences further down the line, but nobody is thinking about that right now.

Why the world should care

Putin’s Q&A session and Nabiullina’s press conference are a neat summary of the differing ways officials view the economy. This year has been one of economic overheating fueled by military spending. However, Nabiullina’s monetary policy (with Putin’s approval) means it will be much harder next year for the Kremlin to boast about economic growth.

Figures of the week

- Russian GDP growth was 3% in the first 9 months of this year, and 5.5% in the third quarter, the State Statistics Service (Rosstat) reported. In manufacturing (which includes the defense industry), growth in the third quarter was 9.9%.

- The share of Russian-made cars sold on the Russian market in the first 11 months of 2023 was 49.5%, the Ministry of Industry and Trade reported. In 2021, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the market share of cars made in Russia (of course, these were primarily produced under European and Asian brands) was 82%. Most of this market share has been assumed by Chinese exporters.

- Inflation in the week of Dec. 5-11 accelerated from 0.12% to 0.2% - but in annualized terms it fell slightly (to the upper end of the Central Bank's forecast range).

Further reading

We’ll Be at Each Others’ Throats’: Fiona Hill on What Happens If Putin Wins