No, Russia is not on the verge of a banking crisis

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy – written by Alexander Kolyandr and Alexandra Prokopenko and brought to you by The Bell. This week our top story is an in-depth look at why claims of an imminent banking crisis in Russia are overblown. We also also examine the signals coming from the incoming Trump administration about future U.S. sanctions policy toward Russia.

Why claims of an imminent financial crisis in Russia are overblown

Ominous projections of a financial crisis ready to engulf Russia have been circulating this week through media outlets and social networks. In short, the theory is that Russia is spending almost twice as much on the war as official figures suggest, pushing the banking system toward a collapse in which the authorities might end up freezing deposits.

What’s going on?

Claims of an imminent catastrophe first appeared in a Substack post on Saturday authored by Craig Kennedy, a Russia expert at Harvard’s Davis Center who spent many years with Morgan Stanley. Kennedy’s analysis was then used by the Financial Times’ economics editor Martin Sundby in an opinion piece published the following day.

Kennedy’s initial post described a “low-profile, off-budget financing scheme” to raise funds for the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. He suggested that sharp increases in corporate borrowing in Russia since the full-scale invasion of 2022 – up more than 60% over two years to 19.4% GDP – were linked to increases in military spending. Apparently, up to 60% of these loans (as much as $249 billion) are funding military-linked businesses, he argued.

Since defense companies are, ultimately, likely to be unable to service these loans, the country could end up in a credit crisis, Kennedy claimed. Some public commentators made a further step, suggesting that, when this comes to pass, the authorities will likely opt to save the defense sector and banks by seizing private deposits.

Rumors of frozen deposits

In Russian-language social networks, rumors of the imminent freezing of bank accounts have been circulating since the fall. In early November, economist Alexei Zubets said in a radio interview that banks might freeze personal bank accounts to help curb inflation. According to him, the authorities might take this step to avoid a run on the banks if interest rates were to be slashed. At that time, deputies, officials and the head of the Central Bank all dismissed the suggestion.However, their words did not reassure Russians who have lived through several confiscations of funds and financial crises (from the monetary reforms of 1991 to the partial freezing of accounts in 1998 and the forced conversion of some foreign currency deposits in 2022). A post about the possible withdrawal of deposits appeared on the popular Nezygar Telegram channel earlier this month – but Nezygar is believed to be linked to a government PR team and the post was likely part of squabbles between officials over interest rate rises.

The rumors were even a part of the State Duma’s most recent attack on the Central Bank. Deputy Alexei Nechayev on Tuesday demanded legislation ensuring that “any Central Bank decision about the savings of ordinary citizens can only be made with State Duma approval.” However, it’s unlikely that this law will ever be enacted – should the authorities wish to do something like this, they would need to act extremely swiftly.

What would a deposit freeze achieve?

Right now, freezing deposits makes little sense. Lending is currently the basis of Russian economic growth, and, if accounts were frozen, then banks wouldn’t be able to extend further loans to businesses.

The argument that a freeze is needed to curb inflation is also flawed: with high interest rates, a mass withdrawal of funds and increased spending seems illogical.

There are also doubts that a freeze could even stave off a credit crisis. Firstly, if such a crisis arises, it would make more sense for the authorities to guarantee all deposits. That would do more to protect the banking system and the economy. Secondly, Russia has fairly strict regulations designed to ensure financial stability, including large capital buffers.

Does Russia have a credit problem?

According to the Central Bank, the overall increase in corporate loans since 2022 is no more than $300 billion. That’s far less than the $415 billion cited by alarmists. More importantly, about two-thirds of this is a result of companies replacing foreign currency debt with ruble debt after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. These new ruble loans are at higher interest rates, but eliminate currency risks. Moverover, they cannot be regarded as war loans.

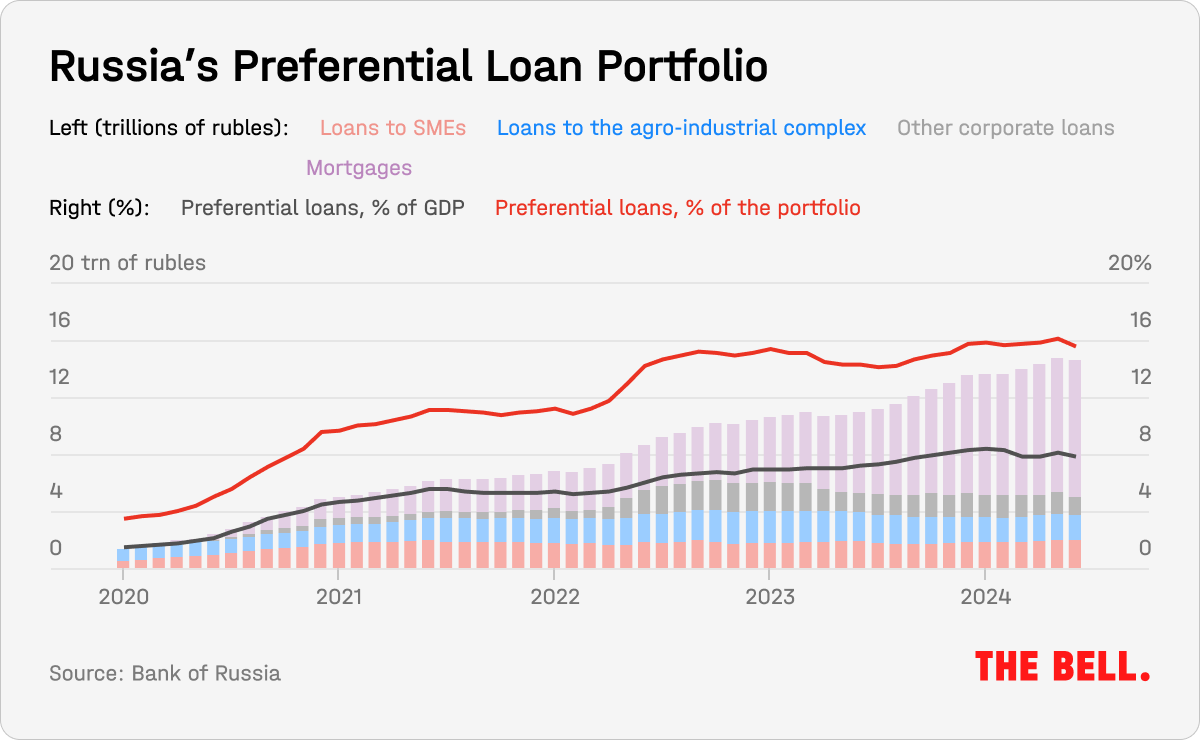

Most importantly, it’s wrong to add this money to official spending figures: all credit subsidies are already reflected in budget data: for example, in the state armaments program, the program to support SMEs, agricultural producers and others.

Even if the corporate loan portfolio has expanded rapidly in the last two years, it’s not a given that this expansion will continue: indeed, there were signs that corporate borrowing was beginning to slow in November and December.

There are also a lot of nuances when it comes to state subsidized loans. According to the Central Bank, the bulk of Russia’s subsidised loan portfolio is made up of developers using the subsidized mortgage scheme that ended on July 1. All these loans cannot simply be branded bad debt. For example, the rates on subsidized loans for developers are heavily dependent on the availability of company funds in escrow accounts – in other words, money received from buyers of future apartments, and effectively owned by the bank, is financing construction. If the total funds in the escrow account is close to 100% of the requested loan, banks are willing to issue loans at low rates since there is guaranteed collateral.

It is emphatically not only the defense sector that is borrowing in Russia right now. Most new loans in Russia are currently being taken out by companies working in wholesale and retail trade, transport and communications, construction, real estate, petroleum and finished metal products. Only the last of these is significantly linked to the defense sector.

Of course, not all military spending is coming straight out of the budget. Contract soldiers receive part of their salaries from regional budgets, for example, and some of the wounded are treated in civilian hospitals. But it seems unlikely that the real cost of the war is twice as much as Russian officials claim. If the war and the defense sector really consumed 16% of GDP, this would have a noticeable impact when it came to production for the civilian sector.

Why the world should care

In our view, all things being equal, it’s unlikely that the economy will implode soon, forcing Russia to scale back its military campaign in Ukraine; or that deposits will be frozen. That doesn’t mean, however, that nothing will ever happen to deposits, nor that the banking sector will always be trouble-free. However, there are far bigger threats to the Russian economy at the moment: for example, a lack of transparent decision-making, little independent expertise, and the classification of much economic data all undermines trust in the authorities. This is more likely to, eventually, lead to some sort of hard-to-predict, man made crisis.

Will Trump increase sanctions on Russia?

Bloomberg reported Friday – four days before Donald Trump’s inauguration as president – about how the incoming U.S. administration plans to use a carrot and stick approach with Russia. If ceasefire talks progress and Russia demonstrates “goodwill,” then sanctions on Russian oil will reportedly be eased. However, if there is no progress, Washington will seek to toughen sanctions.

- The man likely to be Trump’s secretary of state, Marco Rubio, said Wednesday that the new administration will not be shy of using sanctions, but added that it sees them as a lever to achieve peace. Similarly, incoming Treasury Secretary Scott Beasant said Friday that he was “100% in favor of increasing sanctions, especially against major oil companies, until Russia sits at the negotiating table.”

- Bloomberg reported that the ”stick”, should Russia refuse to negotiate, could be further secondary sanctions on buyers of Russian oil, specifically India and China. In effect, that would mean expanding secondary sanctions.

- Other measures available to the U.S. include restricting the passage of vessels insured by sanctioned companies as they try to pass through the Bosphorus or Denmark’s territorial waters in the Baltic Sea (both major export routes for Russian crude). It would also be possible to sanction other Russian companies (Surgutneftegaz and GazpromNeft, which were sanctioned last Friday, produce only about half of all Russian oil exports). The country’s biggest oil companies, Rosneft and Lukoil, still remain free of restrictions.

- The “carrot” if Russia cooperates in ceasefire negotiations could be raising the price cap on Russian oil, which would give exporters access to Western insurance and transportation services. In addition, the administration could permit the purchase of some Russian oil products.

- Removing most sectoral sanctions on Russia is impossible at the stroke of a presidential pen: they were implemented as appendices to legislative acts, and any changes would need to go through Congress.

- Trump now faces the same challenge that outgoing president Joe Biden faced in 2022: how to put pressure on Russia without causing a sharp rise in gas prices for U.S. motorists. However, unlike Biden in 2022, Trump doesn’t have to worry about upcoming midterm elections.

- Last week’s U.S. sanctions on Russian oil showed that there is much more economic pain the U.S. could inflict if it wanted. Since the new restrictions, dozens of Russian oil tankers have been halted, freight from Russia’s main Far Eastern port, Kozmino, has tripled in price, and a barrel of Brent is up $5 to over $80.

Why the world should care

Sanctions will be a major bargaining chip in any talks over Ukraine. By the time negotiations begin (if they begin), it should be at least partially clear to what extent the U.S. is willing to enforce secondary sanctions against buyers in India and China, and how much this will push up prices. This, in turn, will give a sense of how effective taking a “carrot” or “stick” approach might be. The success, or failure, of sanctions depends on how the White House and the Kremlin assess Russia’s financial problems, and the future of the oil market.

Figures of the week

Inflation in Russia might be starting to slow. Between January 1 and January 13, prices went up 0.67%, which suggests annual inflation of 9.9% (it was 9.5% last year). However, January’s figures reflect one-off boosts from increased sales of alcohol and tobacco, a further rise in the recycling fee for cars, higher public transport fares and a weakening ruble. Together with a fall in consumer demand and an increase in consumer borrowing, this could mean inflation will peak in the first half of the year. In the absence of external shocks (such as tighter sanctions) this could pave the way for lower interest rates.

Last year, Russians spent almost 25% more on online purchases than in the previous year. In particular, Russia’s regions are enjoying an e-commerce boom: small and medium-sized cities accounted for 76% of all internet orders and online trade turnover in the regions grew twice as fast as the national average (up to 80% year-on-year). The main reason for this rapid growth is financial inflows to the regions linked to the war (salaries, sign-on bonuses and death payments), as well as higher wages in the civilian sector.

Chinese exporters delivered a record $115.5 billion worth of goods to Russia last year, according to Chinese customs figures published this week. That’s 4.1% more than in 2023. Exports increased despite ongoing problems with payments (Chinese banks are blocking, or returning, payments from Russian businesses because of Western sanctions). Over the same period, China imported goods from Russia worth $129.3 billion (roughly the same as last year). Generally speaking, China supplies Russia with tech and consumer goods, while Russia sells almost exclusively raw materials.