Romanticism, nostalgia, regret: why are Russians discussing the 1990s?

Romanticism, nostalgia, regret: why are Russians discussing the 1990s?

The 1990s are a deeply divisive topic for most Russians: for some it is a reminder of economic disaster, for others it represents opportunity and political freedom. Either way, debates about the decade have intensified in recent years — and parallels are inevitably drawn with current events as the country heads toward another period of political transition.

- Many of these dynamics were on display in an interview (Rus) The Bell founder Elizaveta Osetinskaya did this week with veteran billionaire Peter Aven. During the 1990s, Aven briefly served as a minister under President Boris Yeltsin, before entering business and joining the powerful Alfa Group. In the interview, he said he had several regrets looking back on the 1990s.

- Firstly, Aven said Yeltsin’s victory in elections in 1996 (Yeltsin was controversially bankrolled by a group of oligarchs,and Aven’s business partners were also believed to be involved) was not necessarily the best outcome for Russia.

- Secondly, the billionaire conceded he and his liberal allies were insufficiently democratic. “We were, of course, in favor of economic freedom, but we had — mistakenly I think now — the political idea of forcibly, in an authoritarian way, imposing economic liberalism… it’s no secret that the Pinochet model was very popular in our circles.”

- Preferring Yeltsin to Zyuganov was another mistake mentioned by Aven. Talking about the notorious ‘loans-for-shares’ scheme (which gave the oligarchs the biggest factories for nothing) Aven says that he always considered them a big mistake – although he does not deny that Alfa Group itself wanted to participate in them (and in reality it did get a foot inthe door).

- Now the head of Russia’s largest private bank, Alfa Bank, Aven has become a chronicler of the 1990s: his last book was about 1990s tycoon and kingmaker Boris Berezovsky, and he is currently working on another one. Russia has not “seriously reflected on the 1990s,” Aven said. And he is not the only political veteran keen on revisiting events: Anatoly Chubais, the architect of Yeltsin-era privatization, often discusses the 1990s on social media.

- For much of the last two decades, the 1990s have been used by supporters of President Vladimir Putin as a bogeyman to highlight the contrast with post-2000 stability. But the period still evokes some romanticism: a survey (Rus) released Thursday showed most business people think that, despite the lawlessness and real physical danger, running a business was easier in the 1990s than in the 2010s.

Why the world should care

The debates about the 1990s are important because while the state is trying to picture them as the dark times that no one wants to come back to or remember, they are still the roots of everything happening in the society and business, and the political elite of modern Russia takes its origins from the 1990s as well.

Over half of young Russians want to emigrate

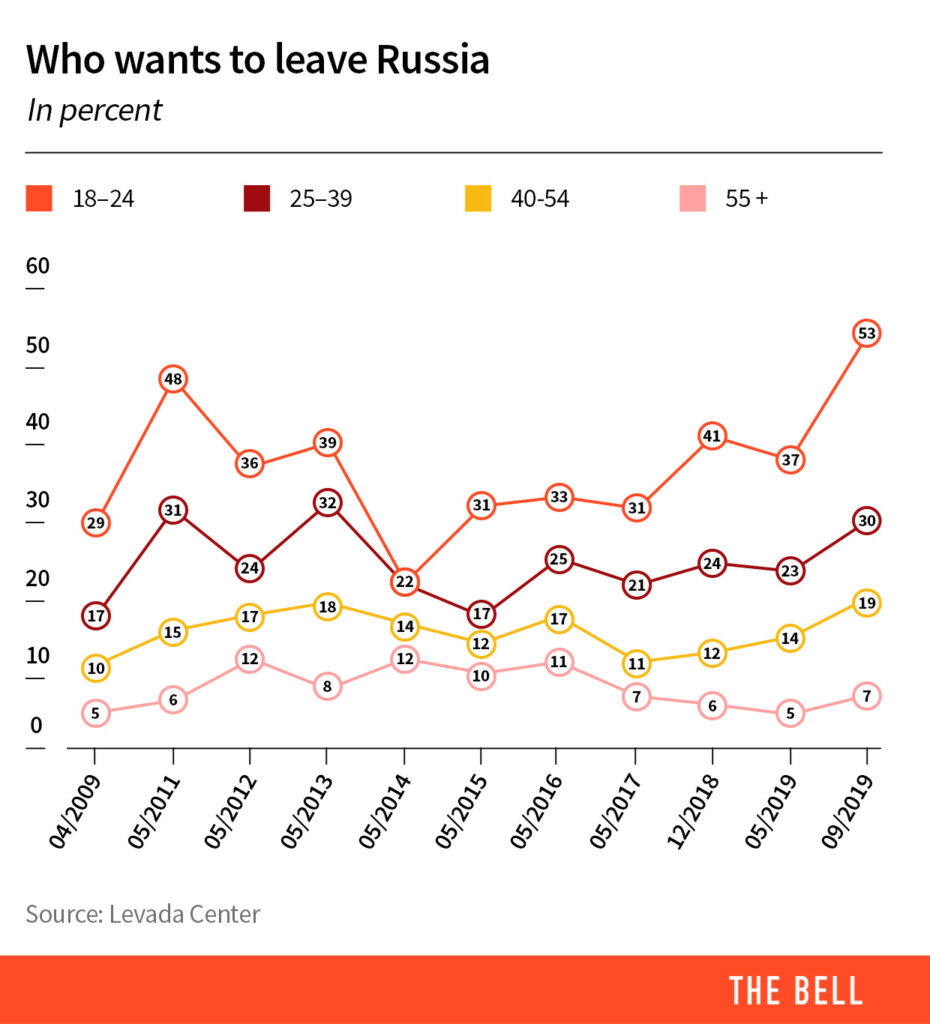

As many as 53 percent of Russians aged between 18 and 24 want to leave the country, according to a survey (Rus) published Tuesday by independent pollster the Levada Center. This is the highest figure in a decade: put simply, more and more young people do not have faith in the path the country is taking.

- The results. A desire to emigrate has grown among young people since 2009, but it rose by 16 percentage points between May and September. This was a period that saw the brief arrest of journalist Ivan Golunov on false drug charges and protests over the barring of independent candidates from Moscow elections.

- Among people of all ages, 21 percent want to leave the country, the highest level since 2013. In addition to young people, the other group increasingly keen on leaving are people in a higher income bracket (28 percent want to emigrate).

- Why? Worries over their children’s future is the main reason people cite for considering emigration (45 percent of respondents). The second most popular reason is the economic situation, and the third is the availability of better medical treatment abroad.

- Politics? Disapproval of Putin is significantly higher among those considering emigration (73 percent) than the country’s average figure (54 percent).

- Not all agree. The day after Levada Center’s poll was published, state-owned pollster VTsIOM unexpectedly released (Rus) a similar survey. This said only 5 percent of young people want to move abroad permanently, while 41 percent want to see the world by studying or working abroad before returning to Russia. Why such a big difference? It’s not entirely clear, although it’s possible the questions were asked in different ways (VTsIOM did not say how it formulated its question).

Why the world should care

Everyone worries about their children’s futures and healthcare. But the mood is changing among young people; the post-Crimea annexation euphoria that led to less talk of emigration has definitely passed. And it will be challenging to convince them otherwise: between 2016 and 2018, the number of young people getting their news primarily from tightly controlled state-owned television fell from 75 percent to 42 percent.

Moscow court approves facial recognition system

The first court case in Russia about facial recognition systems ended this week with a victory for the state. Moscow-based activist Alyona Popova tried to sue the authorities for what she said was her illegal identification at a protest using a facial recognition system. The lawsuit showed no-one knows what will happen to all the personal data gathered by thousands of new cameras installed across Moscow.

- Popova staged a one-woman picket last year at which she was arrested and subsequently fined by a court for violating protest laws (any demonstration with more than one participant in Russia requires permission from the authorities). During the court hearing Popova requested video from the city’s security cameras to prove she had been alone and was shocked to discover footage in which her face was zoomed in on by a magnitude of 32 times. Deciding this was a sign of the use of a facial recognition system, she filed a lawsuit.

- She said that, when approached during her picket, police officers did not ask to see her passport — meaning she had already been identified by camera. She argued that using someone’s biometric data without their approval is only permissible in exceptional cases, and that her case was not one of these.

- The court came to a different conclusion, ruling that police identified Popova by comparing the zoomed-in images with photographs — and that no biometric data was collected. Some lawyers have expressed doubts (Rus) about this logic.

- Moscow’s facial recognition system has been in operation since 2017, and officials have pledged to install a total of 200,000 cameras, half of them this year. If completed, it will be the world’s second largest facial recognition system after those in China. The official explanation is that the system will help to catch criminals, but there is huge potential for abuse. The first confirmed use was at a protest organized by opposition leader Alexei Navalny in 2017, after which an anonymous blogger uploaded personal data harvested from cameras.

- Popova said her lawsuit was a way of drawing attention to the issue and finding out who can access information collected by facial recognition systems. But she had little success: the court failed to explain who has the legal right to use this data.

Why the world should care

Balancing security needs and the risk of becoming a full-blown surveillance state is not just a Russian concern. But the secrecy about facial recognition systems in Russia is particularly striking. It is not clear who has access to the data, or its legal status, fuelling fears it could be used as political pressure or find its way onto the black market.

IN BRIEF

Russia closes largest ‘privatization’ deal in 3 years

There were echoes of the 1990s in business Wednesday as Russia closed its largest privatization deal since 2016. State-owned Russian Railways sold a controlling stake in its largest container shipping company, TransContainer, for almost $1 billion. To what extent it was a full privatization, however, is open to question: winner Sergei Shishkarev has said the majority of the purchase will be funded by credit from state-owned banking giant Sberbank. Either way, it ends the long saga of the state’s sale of TransContainer, which began in the mid-2000s with preliminary discussions and a valuation of $3 billion (compared to $2 billion today). But the process dragged on for over a decade. Ultimately, the 50 percent-plus-two-shares stake was won at auction by ex-State Duma deputy Shiskarev, head of the little-known Delo Group. To many’s surprise, he outbid the only other participants, billionaires Roman Abramovich and Vladimir Lisin.

Siri, who does Crimea belong to?

It emerged this week that U.S. tech giant Apple has decided to label Crimea as a part of Russia, more than 5 years after the region was annexed. For Russian users in Russia, Apple’s ‘Weather’ and ‘Maps’ apps now show Crimea as being Russian territory — while, for Ukrainians, Crimea remains Ukrainian and for other users around the world it is a disputed territory. The move prompted furious protests from Ukrainian officials, but Apple is following in the footsteps of Google, which made the same switch in March. The changes come after months of negotiations between Apple and Russian Duma deputies.

Cyber-cows in imaginary pastures

While Elon Musk has just launched his Tesla truck, Russian innovation is beating its own path. The RusMoloko dairy farm near Moscow announced Monday that it had begun testing (Rus) VR masks for cows. Local veterinarians and an unidentified IT company came up with the idea. The masks apparently show scenes of green summer pastures, which reduces cow stress levels and improves the herd’s “overall emotional mood’ — and happier cows mean increases in milk production. Considering Moscow only has about 50 sunny days a year, the VR masks may also have a market among vitamin D-starved Muscovites.