Russia after the election: some fight over government roles, others for permission to quit

Photo credit: Kremlin.ru

1. Following the presidential election, some politicians are fighting over government roles, while others are lobbying — for permission to quit.

What happened

On March 18th, the Kremlin got what it wanted from the presidential election — Vladimir Putin had his best ever result, receiving 77% of the vote with a 67% turnout. The main question now is how will he execute this mandate. In external politics everything is clear — the conflict with the West, unfortunately, will only escalate. But what about the economy? Will Putin use this level of public support (even if it’s a formality) to carry out long overdue, unpopular economic reforms?

- We got the first taste of Putin’s future economic policy a few days after the election. On March 22nd, we learned that the government is discussing increasing the personal income tax and VAT rates. But we will only be able to make preliminary conclusions about how this money could be used and if some kind of economic reforms will also be undertaken in May, after the government is formed.

- The one and a half months between the presidential election and the inauguration are always a time of intense fighting for both cabinet posts in the government and management roles in state companies. The latter are considered more prestigious and profitable vis a vis thankless economic jobs in the government. Therefore, young, ambitious bureaucrats battle for cabinet positions, while experienced members of the government lobby for permission to step down from their posts.

- “The number of high ranking dignitaries determined to retire from public service, using their formal right to resign during the transition period, is growing. ‘Our guy made a deal, they are letting him go,’ this phrase was used by officials reporting to several dignitaries in Medvedev’s cabinet,” — political commentator, Konstantin Gaaze, wrote in his column (Russian) on Carnegie Moscow Center’s website. This “they will let (him) go” means that a government official is granted permission to go into the private sector, to join a state company, or to take on a civic or scientific role — this ends up being almost the only coveted award for many of those who make up the backbone of the central functions of the Russian government bureaucracy.

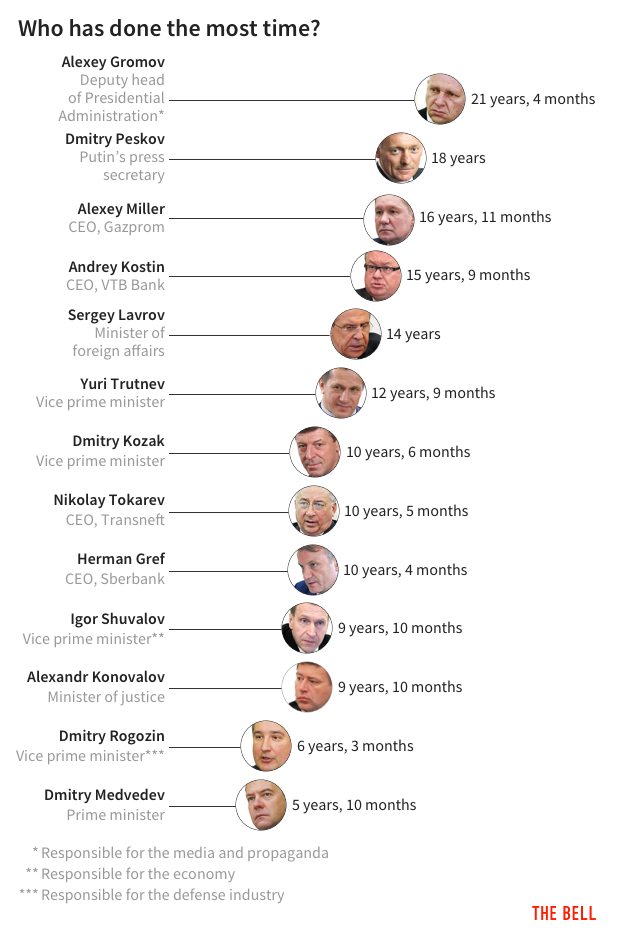

Dmitry Medvedev is likely to remain Prime Minister. It’s not easy to speculate about the future of the remaining ministers and CEOs of state corporations. But it’s possible to speculate who might give up their posts (and who “made a deal, and they let him go”), if you take a look at the list of high ranked Russian bureaucrats and CEOs who have been in their roles for the longest period of time. We put the list together for you:

Why the world should care

The new government’s constellation will say a lot about Putin’s plans for his new term, for the Russian economy and for other areas. For example, Foreign Minister Lavrov is one of the longest serving members of the government, and there are already rumors swirling about his possible retirement. CEOs of state corporations are no less influential than ministers, and in some cases, they are even more so.

2. Former Finance Minister Kudrin drew up a reform program for Putin. But Kudrin himself is unlikely to lead the reforms.

What happened

Alexey Kudrin, former Finance Minister and one of Vladimir Putin’s closest advisors, was the first to make an almost official announcement of his desire for a minister role in the new government, with an article for Kommersant, a major business newspaper. Kudrin was forced to resign in 2011, but he remained close to Putin, and in 2016 Putin tasked Kudrin’s think tank with developing a program for Russia’s economу between 2018-2024.

In his article, Kudrin outlines, in his opinion, what the government should focus on over the next two years — until the next election cycle (State Duma elections in 2020). His main points:

- The government has only two years to carry out reforms — until the beginning of the Duma election cycle in 2020. Kudrin calls this “the window of opportunity”.

- The primary goal should be reform of the system of state management (reducing the number of bureaucrats and the budget of the state bureaucracy by one third, removal of ministers who fail to introduce reforms). The next target should be increasing spending on education, health care and infrastructure (using those funds generated by reductions in defense and security spending). Thirdly, “transparent and predictable policies” should be established (for example, the development of a predictable and clear tax policy).

- Kudrin’s article, of course, doesn’t say anything about who should lead these reforms. But it’s difficult to interpret the article as anything less than the beginning of a new battle for a position in the new government.

But there is one problem. There are so far no signs that Putin plans to change his Prime Minister. Dmitry Medvedev and Alexey Kudrin’s personal relationship couldn’t be worse. It was Medvedev, when he was still President, who very publicly and loudly fired Kudrin from the government following a long conflict between the two (Kudrin was against an increase in social spending for which there was no room in the budget at that time). It is very unlikely that Kudrin and Medvedev could work effectively together in one team — this means that a Medvedev-led government would sabotage a reform program.

Why the world should care

Without reforms, the economy will continue to deteriorate, and agressive foreign policy and mobilization over the conflict with the West will likely remain the only way to maintain popular support for Vladimr Putin.

3. One of the developers of the nerve agent “Novichok” sold it to mobsters.

What happened

This week didn’t offer any more clarity as to who poisoned former Russia spy Sergey Skripal and how. However, a lot was discovered about the top secret nerve agent “Novichok” — most importantly, from several interviews with the chemists who helped develop the substance. One of these scientists, Vladimir Uglev, gave The Bell an exclusive interview — here it is in case you missed our dispatch on Wednesday. What is clear:

- Contrary to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ statement, “Novichok” definitely did exist. Uglev confirmed this in his interview with The Bell, as did another chemist who worked on nerve agents, Leonid Rink, in his interview with government information agency RIA Novosti (owned by the same holding which controls Russia Today).

- The nerve agent fell into criminal hands at least three times. This same chemist, Leonid Rink, was questioned in a 1990s criminal case surrounding the murder of banker Ivan Kivelidi. The case files include Rink’s testimony where he admits (Russian) that between 1994-1995 he synthesized and sold doses of “Novichok” to people with connections to organized crime. Rink was accused of two separate felonies, but these cases were later closed for unclear reasons.

- A few dozen people knew the formula for “Novichok”, Vladimir Uglev told The Bell.

Why the world should care

The international scandal continues to heat up, Boris Johnson is already comparing Putin to Hitler. The Russian MFA’s announcement and its refusal to accept the existence of the nerve agent appear absurd. But case files provide concrete evidence that “Novichok” already found its way into criminal hands more than once, which raises questions about the whole story. These developments cleary warrant a comprehensive and public investigation by Russian and British authorities.

4. Russian media outlets have come together for the first time in many years after the Duma’s cynical reaction to sexual harassment accusations against a Duma deputy.

What happened

Three female journalists accused Leonid Slutsky, Duma depty and head of the Duma’s international affairs committee, of sexual harassment in February. After multiple requests, the Duma ethics committee finally reviewed the accusations on Wednesday.

A full transcript of the hearing is here, and it is truly shocking. Despite the audio recording, the committee didn’t find anything reprehensible in Slutsky’s behaviour, and accused the female journalists of a seeking a provocation on the eve of the presidential election.

Over the course of the next day, almost all major Russian media outlets, with the exception of state-controlled media, announced a boycott of the Duma and recalled their journalists from parliament. In response, Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin stripped the journalists of their official accreditation. We will see next week what will happen next.

Why the world should care

Russia can appear to be a strange place, in which there is nothing but Vladimir Putin riding bare-chested on a horse and his corrupt friends. But the reality is far more complicated. There are more normal people than abnormal, and the highly cynical response by the ethics committee might just spur all the normal people to unite in this #metoo moment for Russia.

Peter Mironenko, The Bell

This newsletter is made with the support of the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley.