Russia has a spending problem

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — written by Alexandra Prokopenko and Alexander Kolyandr and brought to you by The Bell. This week our top story is Russia’s record budget deficit means and fresh stagflation fears. We also highlight how the latest Western sanctions on Russia’s oil industry aren’t working.

Hey, big spender

As expected, the central bank left its two-decade high base rate unchanged at 21% on Friday. However, it unexpectedly raised its inflation forecast significantly. Prices that continue to rise and lending that declines only gradually are delaying the start of any rate cutting cycle, and increasing the likelihood Russia could face a dangerous combination of low growth and high inflation. The underlying reason for high inflation is still the same: high government spending.

Record budget expenditure

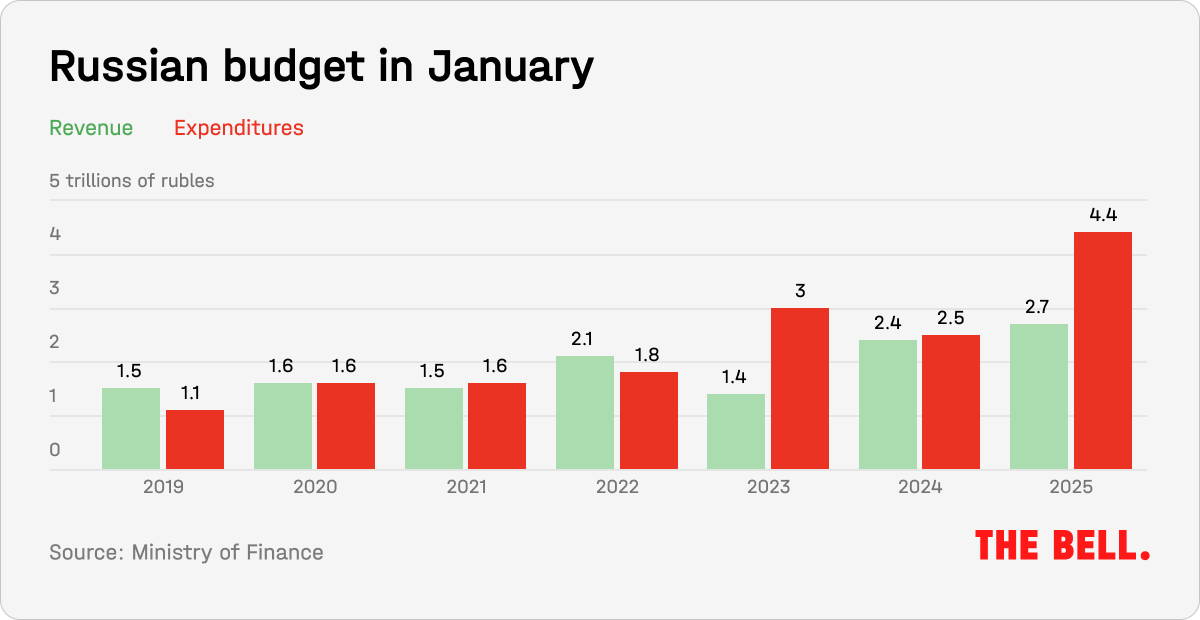

Despite Putin’s order to bring inflation under control, the Russian government continues to stoke demand with high spending. This week the finance ministry said revenue was up 11.4% year-on-year in January to 2.6 trillion rubles ($28 billion) — but expenditure set a new record, jumping 73.6% to 4.37 trillion rubles ($48 billion). Government orders accounted for 1.5 trillion rubles, an increase of 242%.

Thus, the budget deficit was 1.71 trillion rubles (0.8% of annual GDP) — also a record for January. The finance ministry said this was due to advance orders and promised that spending would return to expected levels throughout the rest of the year. There was a similar picture in 2023 and 2024. Government spending in January 2023 exceeded 10% of the plan, while in 2024 a similar anomalous leap came in February. Each time, the finance ministry has said it was due to payments for advance orders — and in the last two years, the deficit level did indeed stabilize over the following months.

The authorities do not disclose exactly where such advances are spent. But, as a rule, the most resource intensive budget items at the start of the year are the purchase of weapons and military hardware under state defense orders, financing the army, infrastructure contracts (primarily road-building), acquiring fuel for the “northern delivery” (government shipments of supplies to the far north) and preparing for agricultural work in the spring. The finance ministry also highlighted that January’s spend is partially funded by additional oil-and-gas profits in 2024.

Last month’s record-breaking expenditures essentially mean an easing in fiscal conditions — in effect undermining the Central Bank’s efforts to slow inflation. “To return to low inflation, it is necessary to maintain a strict monetary policy for an extended period and adhere to the approved budget parameters for 2025-2027,” the bank’s analysts wrote earlier this month. The finance ministry promises that these advances will not affect the overall quarterly spending dynamic. If that proves to be the case, then we can talk about Russia having started its transition to a strict budgetary policy.

In order to remain within the planned parameters of a 1.17 trillion-ruble deficit over the course of the year, the finance ministry should spend an average of 3.37 trillion rubles a month over the rest of the year. That means the overall budget stimulus — expenditure minus income — would drop into negative territory within the first half of the year. In combination with a slowdown in lending, that should bring about a rapid cooling of the economy.

But it is far from clear that the government will succeed in staying within its spending guidelines: since the invasion of Ukraine the federal budget has seen consistent spending increases, peaking in 2024 with a 21.7% rise compared with 2023.

What about economic growth?

While budget spending increases, the banks are lending less. Both the corporate and consumer lending portfolio went down 0.5% in January in real terms, according to a Sberbank report. In December, corporate borrowing was down 0.2%, the Central Bank calculated, but this was largely due to the repayment of a large number of foreign currency loans.

Both lending and the rate of economic growth in war-time Russia are closely linked to government spending dynamics. In 2024 state spending fed a rapid rise in borrowing (+17.9%) despite high interest rates. Given the existing structural restrictions — labor shortages and no spare production capacity — this caused economic overheating and accelerated growth.

As early as 2023, the finance ministry wanted to return to the “budget rule”, which not only obliges the government to save oil and gas windfalls in the National Welfare Fund, but also limits budget spending. But the Kremlin’s priorities are very different: the state is accelerating military spending and stimulating demand. Moreover, replenishing the fund may prove impossible due to the lag between projected and actual oil prices.

In 2024, the Russian economy grew by 4.1%. In nominal terms, GDP cleared 200 trillion rubles for the first time in history, which PM Mikhail Mishustin proudly presented to President Vladimir Putin as a “historical maximum.” These dynamics were only possible due to rising prices. The fact is that nominal GDP measures the cost of all goods and services produced in an economy at current prices. If inflation pushes up prices, then the overall GDP figure goes up, even if actual volume output is unchanged. The inevitable increases in wages, prices for raw materials and other costs also increases the total money turnover and, therefore, GDP.

According to Rosstat’s preliminary estimates, the GDP deflator index was 8.9% last year. The index measures the price increase in all the products/services produced in the economy, as opposed to inflation, which measures price increases in a basket of consumed goods/services. This means that price rises contributed almost twice as much to nominal GDP growth as output increases. In other words, if you look at nominal GDP in isolation, you might mistakenly assume that the economy is growing healthily. However, in reality, growth is driven chiefly by inflation and not by any productivity gains.

The economic development ministry and Central Bank are already concerned about the increasing risk of a fall in oil prices, potential increases in problematic corporate debt and possible future budget constraints. Reuters wrote about such fears this week, citing documents prepared for discussion at a government meeting on Feb. 4 that suggested the ministry sees an increased likelihood of recession before inflation slows — in other words, the return of stagflation.

The central bank also expects a slowdown in growth. On Friday, the regulator published its revised forecasts, in which GDP growth for 2026 was pushed down to 0.5-1.5%, from 1-2% in its previous forecast. Expectations for the current year, by contrast, went up to 1-2% from 0.5-1.5%. Both suggest that Russia’s economic growth will not outstrip the global average, as promised by the Kremlin. Meanwhile the inflation forecast for this year was increased sharply — from 4.5-5% to 7-8%, suggesting that fears of stagflation are well-founded.

Why the world should care

If budget spending returns to normal, then the slowdown in borrowing and a weaker budget stimulus will help to tame inflation. But this will also lead to a slowing of economic growth, which the Kremlin sees as a symbol of Russia’s invulnerability in the face of Western sanctions. Maintaining subsidies for industries (or, as the Kremlin calls it, “developing the supply-side economy”) also fuels inflation and forces the central bank to raise interest rates and fight off demands to encourage cheaper borrowing from manufacturers and ministers seeking immediate growth. If everything stays the same, there will be a high risk of galloping inflation coupled with sluggish growth. That doesn’t only harm the well-being of ordinary Russians, it creates long-term problems due to underinvestment. The state’s task of stabilizing the economy is reminiscent of the wolf, goat and cabbage logic test: there is a solution, but not a quick one.

Oil sanctions still aren’t working

Despite Western sanctions on its shadow fleet, Russia earned more from oil exports in January than in December. And in 2024, it earned more than in 2023.

- In January, there was no decline in oil and petroleum exports from Russia. They remained at 7.4 million barrels a day, according to the latest IEA monthly report. In dollar terms, exports were up almost $1 billion compared to December, reaching $15.8 billion. The reason was those very sanctions against the shadow fleet — which drove up global prices for benchmark Brent crude to $82/barrel — and that the grace period allowed Russia’s customers to accept deliveries that had already been shipped on tankers that fell under sanctions.

- All Russian oil sold in January exceeded the G7’s $60 cap. But the discount on Russia’s Urals blend compared to benchmark Brent crude was up $1 to $12.70 a barrel, the IEA said. The discount on the ESPO grade, which is highly sensitive to Chinese policy, went from $2.50 to $8.60. Chinese ports, trading heavily in Far Eastern oil, made a show of delaying sanctioned tankers, pushing up freight costs.

- The structure and geography of supplies were unfavorable for Russia: 84% of maritime exports of Russian oil in January were carried on the shadow fleet, primarily to China, India and Turkey. EU countries still received oil via pipelines.

- Overall, Russia earned $189 billion from oil exports in 2024, slightly more than in 2023. Export volumes were up 2.7%.

Why the world should care

The impact of the latest US sanctions against two Russian oil majors and the shadow tanker fleet has yet to hit Moscow’s finances. Instead, the transition period is proving profitable for Russia. The greatest threat to Russian oil exports — and to the balance of payments and the exchange rate — would be US secondary sanctions against the main purchasers of Russian tanker oil: companies in India and China. The prospect of these sanctions, or a promise not to impose them for political reasons, represent the biggest unknowns for Russian oil right now.

Figures of the week

From Feb. 4-10, weekly inflation increased from 0.16% to 0.23%. Annual inflation was up from 9.92% to 9.99%.

High interest rates on savings and rising household incomes have led to the biggest rise in bank deposits for 14 years. The volume of insured funds in deposits was up 25.4% in 2024, reaching 75.9 trillion rubles.

The volume of preferential mortgage loans in 2025 will drop by a third compared with last year, anticipates state corporation Dom.RF, which runs the preferential mortgage programs. Dom.RF expects to issue 400,000-450,000 loans this year, worth a combined 2.3-2.6 trillion rubles. In 2024, it issued 636,000 loans worth 3.4 trillion rubles under preferential programs.

Further reading

Putin Won’t Settle for Less Than a U.S. Betrayal of Ukraine

What Does Putin Hope to Gain From Ukraine Talks With Trump?

Vance Wields Threat of Sanctions, Military Action to Push Putin Into Ukraine Deal