Russia hooked on cheap thrills of war-fueled economy

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. This is Alexandra Prokopenko, and before we get into the analysis, I’d like to introduce you to Alexander Kolyandr, an economic analyst with years of experience at Credit Suisse, The Wall Street Journal and the BBC. We worked on this newsletter together and, in the new year, Alexander will become one of The Bell’s regular contributors.

For our last newsletter of 2023, we’ll take a long look at the state of the Russian economy, the pressures of war, and what we can expect next year.

Can the Russian economy survive another year of overheating?

If you believe President Vladimir Putin, the Russian economy is ending the year on a high: annual growth of 3.5%; unemployment at a record low of 2.9%; and the ruble significantly stronger than its year-low of over 100 against the U.S. dollar. Admittedly, inflation on some goods is high, but, according to Putin, this is a “failure” of the government that can be put right. Putin’s optimism has even led some to doubt the effectiveness of Western sanctions.

However, Putin is peddling a misleading picture. All is not well with the Russian economy (more on this). And the sanctions imposed by the West after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine are working – just not as fast as Western politicians would like. The Russian economy is gradually returning to what it looked like in the late Soviet period or even NEP (New economic policy) in 1920s: while the consumer market was dominated by private enterprise, almost everything else – including foreign trade – was largely controlled and calibrated by a Kremlin seeking to boost defense output, and ensure social stability.

All depends on the military situation

The two main unknowns next year are how the military situation in Ukraine will unfold, and possible political changes after the re-election of Putin in March. Military experts say that 2024 could be a good one for Russia’s forces, not least because the Kremlin feels increasingly confident that the fighting is going in its favor.

- The Kremlin’s confidence means the likelihood of a truce falls – Putin has no need to make concessions if he believes time will make his position stronger.

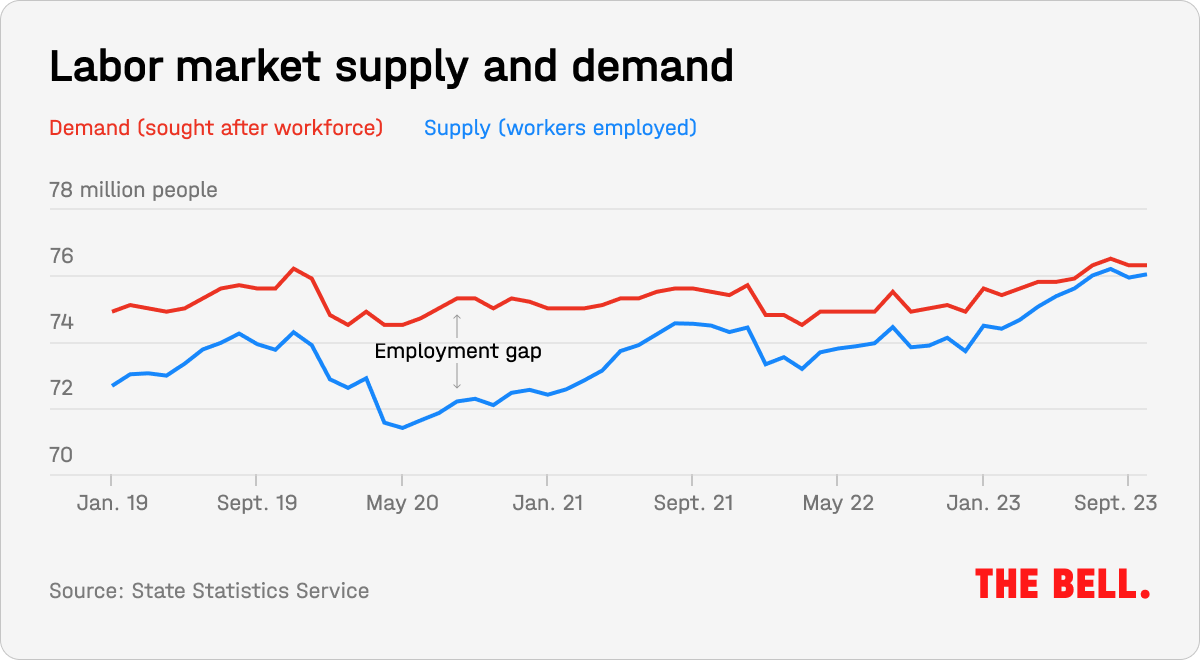

- Since the full-scale invasion in Feb. 2022, Russia has sustained between 270,000 and 315,000 casualties (killed or wounded), according to U.S. estimates. If the war drags on, losses will continue. From an economic perspective, this drains the labor force, and pushes spending higher.

- At present, the families of dead soldiers receive a one-off payment of 5 million rubles, and are eligible for insurance payouts of 3 million rubles. Some Russian regions make additional payments. Wounded soldiers are handed between 3 million and 5 million rubles. Military analysts say that Russia’s ratio of dead to wounded in Ukraine is likely to be 1:4, which means the Kremlin has already paid about half a trillion rubles to the families of dead soldiers. About 1 trillion rubles more has been paid to the wounded.

- For the moment, Russia seems to have solved its manpower shortages by increasing salaries for contract soldiers, and introducing partial mobilization. But problems remain. “The issue of rotation and the lack of people to carry it out will remain a factor in the coming year,” military analyst Michael Kofman said on X (formerly Twitter) earlier this month. While Putin has claimed the army recruited 486,000 contract soldiers in 2023, it is unclear how quickly they are reaching the front.

- If Russia goes on the offensive next year, a further wave of mobilization is possible. Much of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions, which Russia formally annexed last year, remains under the control of Kyiv. And Putin pointedly stated earlier this month that Odesa – and all of south-east Ukraine – was “Russian.”

- However, with réal wages rising, there is lower incentive for a potential contract fighter to risk his life for a shrinking premium on a peaceful job. This might push military payouts higher.

Post-electoral trap for the government

Another risk is Russia’s March presidential election. While there is no doubt about the winner, there is speculation about whether Putin could appoint a new prime minister after the vote. “Everybody expects changes, especially since they are long overdue,” one official told The Bell. “People are discussing different options, but it’s Putin’s call.” A lobbyist for one state-owned corporation said: “Some officials in the Presidental administration are already preparing to move into the government, and government officials are heading to Dubai.” Putin has said nothing about replacing Mishustin (nor has he hinted that Mishustin will keep his job).

On one level, this sort of speculation is natural as officials anticipate changes that have been put on hold due to the war. Conversely, the reshuffle that typically follows a presidential election leaves the system briefly dysfunctional for the period of formation of the new cabinet, deputy prime ministers, ministers, and others. As a result of the 2020 constitutional amendments, Putin is now only able to change the prime minister. But even this step is fraught with unpredictable consequences as the government faces the complex task of cooling an overheating economy, paying for the war and supplying the front.

Overheating, overheating

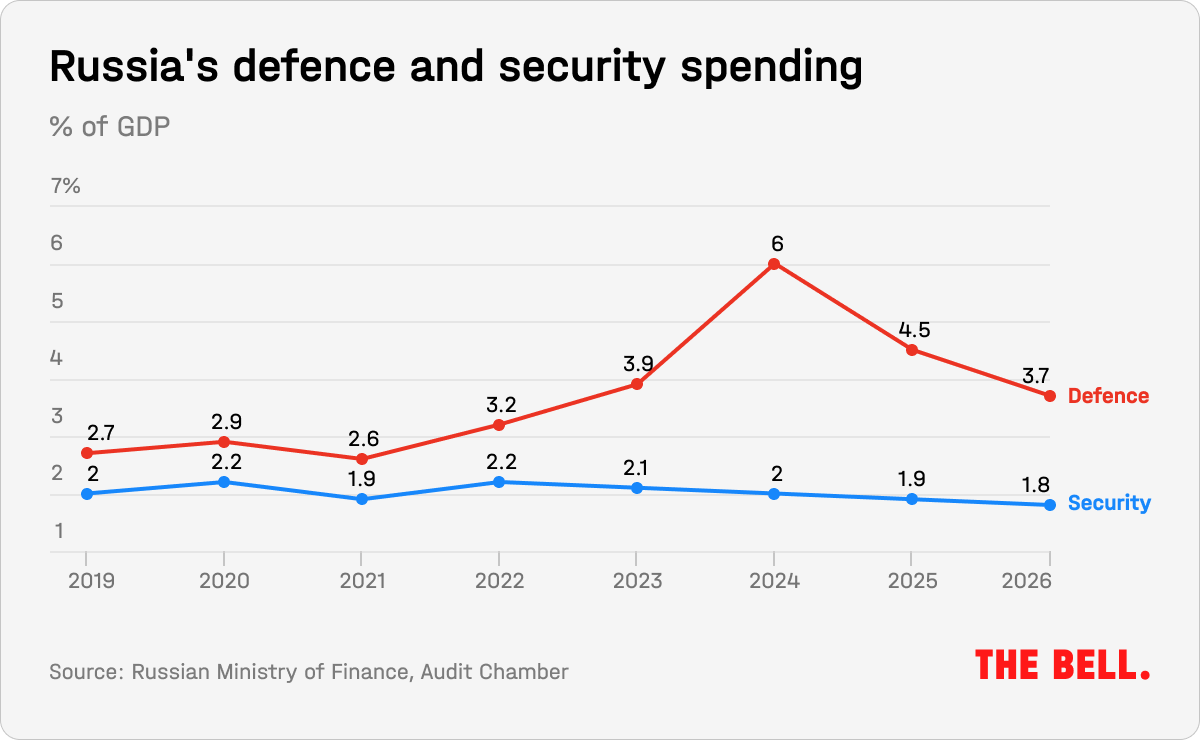

This year’s rapid economic growth has been fueled by a record 32 trillion rubles of state spending, much of which went on defense. Industrial output grew 3.6%; manufacturing expanded at 7.5%; and military-linked production increased at double-digit rates. The war has changed the structure of Russian industry, with the defense sector increasingly important. Industrial capacity utilization is at 80.9%, and factories are running three shifts a day. Unemployment figures indicate almost full employment. Double-digit pay rises are fueling a wage-price spiral. As salaries rise, people spend more, and prices go up.

There are no more reserves to increase supply in the economy. Therefore, growing demand will only lead to higher prices. And overheating may lead to unrealistic optimism – on behalf of households and companies – about future income prospects, resulting in more borrowing. Such a trend is already visible in the mortgage sector.

However, Putin has acquired a taste for the cheap thrills of an economy on war footing. In 2024, spending is planned to be 36.5 trillion rubles, more than a third of which will go on the defense sector and various wartime payments.

Interest rates will stay high

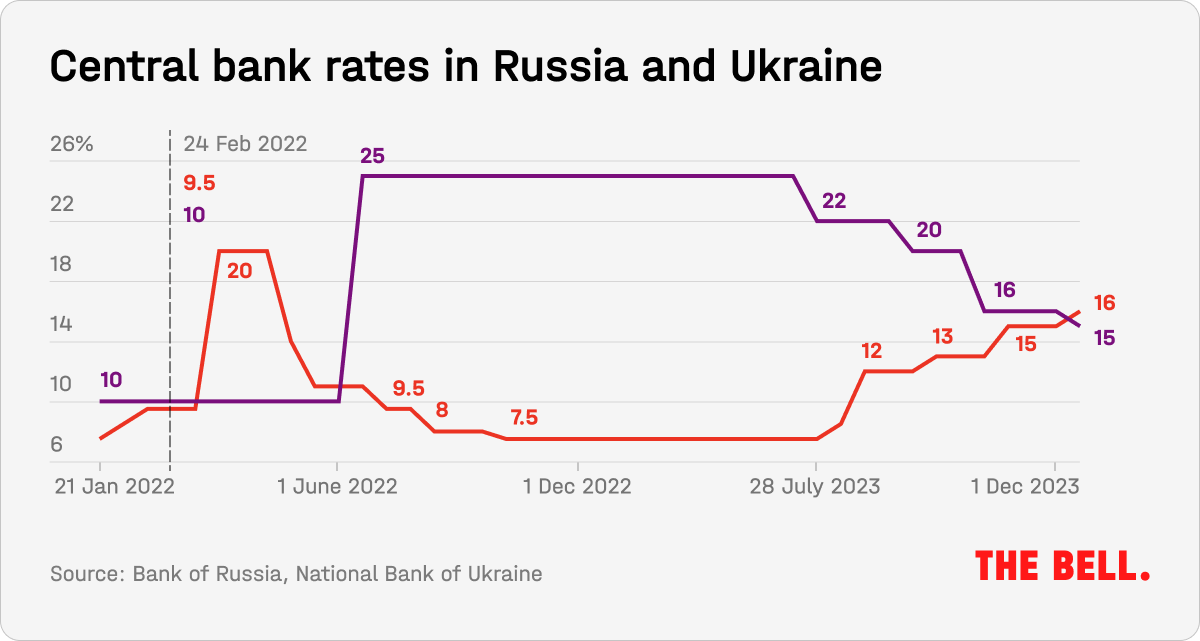

Prices in Russia in 2023 rose by at least 7.5%. Core inflation has posted four successive months of double-digit growth, as Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina observed in a press conference earlier this month. In particular, she highlighted the service sector where prices have grown 14% over three months. The official inflation forecast for next year is 4.5%, although many analysts are doubtful – instead predicting between 5% and 6%. Inflation puts pressure on the budget: indexation of salaries, social benefits, pensions and other state payments depend on its level.

To cool the economy, the Central Bank raised interest rates to 16% at its final board meeting of 2023. In doing so, the bank has given itself plenty of room for maneuver. Even though we’re likely approaching the end of the bank’s tightening cycle, the rate is likely to remain in double figures through next year (predictions say somewhere between 12.5% and 14.5%). At the same time, companies continue to borrow aggressively, even at double-digit rates, which points to exceptionally high inflation expectations. For the Kremlin, high rates not only mean endless complaints from industry lobbyists. It’s also an image problem - healthy economies don’t need double-digit interest rates.

Strikingly, just three years ago, this kind of interest rate would have been considered extreme. But, after two years of war, analysts have spoken of the “everyday” nature of the bank’s recent decision. For regular Russians, it means rates are prohibitively high on any type of loan that is not subsidized by the state. However, it’s exactly those subsidies, along with government spending, which are the main reasons for the rate hikes.

Major companies such as carmaker AvtoVAZ and state-owned Russian Railways have already asked the authorities for subsidies to enable them to service corporate debts while high interest rates last. The head of oil giant Rosneft, Igor Sechin, has gone even further, demanding the Central Bank should agree interest rates with leading exporters. Up to now, Putin has backed Nabiullina in her argument with such lobbyists. However, the Central Bank has had to concede ground on less fundamental matters – for example, when deciding on the mandatory sale of exporters’ foreign currency earnings in the fall.

Misplaced investment

It’s not the first time in recent Russian history that the government has resorted to large-scale economic stimulus. For example, during the Covid pandemic, anti-crisis aid was worth 2.7% of GDP. But in 2022-23, it was significantly larger – according to official Finance Ministry figures, it was equivalent to some 10% of GDP.

Kremlin largesse in 2023 was not so much investment in economic growth as in structural rebuilding: replacing lost imports, expanding the defense sector, and creating a parallel transport and logistics infrastructure. Thus, investment in manufacturing amounted to just 2.75 trillion rubles, only a little higher than pre-pandemic levels. Investment in transport and logistics was also up – about on a par with the extraction industries. However, investment in wholesale and retail trade, as well as agriculture and construction, has declined – mostly as a result of the high borrowing costs.

We can expect this sort of dynamic to continue in 2024 given that spending remains tilted in favor of defense, and interest rates will stay high. Production increases will be limited by sanctions, even if Russia and Ukraine confound expectations and enter peace talks. It’s unlikely there will be any major fiscal problems before the end of next year, but the risks of such a scenario will increase over time.

The West will fine-tune sanctions

Having accepted that the fighting in Ukraine is unlikely to end any time soon, and that sanctions cannot completely isolate Russia, Western countries are steadily revising their sanctions strategy. They are moving toward more targeted restrictions.The U.S. (primarily) and Europe (to a lesser extent) will seek to tighten bans on imports of dual-use technology, microchips and production equipment. At present, Russia can avoid restrictions by buying via third countries, and using shadow import schemes. Now, it’s likely that Western tactics will be to try and break these chains.

In particular, companies operating out of third countries – from Turkey and China to UAE and Kazakhstan – will be in the spotlight. Western nations will try to increase the risks associated with violating the letter or spirit of sanctions so that companies and governments will themselves prefer to avoid selling to Russia. At the same time, legislative and voluntary embargos on the sale of consumer goods to Russia will remain, affecting anything from cars and parts to clothing and cosmetics. Russia has workarounds, but these will get more difficult with time, driving up the prices of imports even further.At the same time, the West is likely to seek to tighten the current oil sanctions. Up until now, the European Union has been unable to halt the sale of second hand tankers to Russia due to opposition from Mediterranean countries. These vessels have formed the basis of Russia’s “shadow fleet,” which transports its oil to buyers. The G7 has also failed to make its oil price cap effective – but it is expected to continue efforts to do so in 2024.

It’s hard to imagine the West could, for example, close Turkish and Danish waters to vessels carrying Russian oil sold for more than the price cap (although the Baltic Sea may be a more realistic target than the Dardanelles). However, secondary sanctions against traders, insurers and freight companies could have an impact, pushing up costs and lowering Russia’s oil revenues. Other raw materials exported by Russia are similarly vulnerable. Of course, sanctions would be less effective if oil prices fall, but the effect on the Kremlin’s coffers would be the same.Ultimately, sanctions will end up having an impact on the balance of trade, and undermining the ruble. This means that, for all the Finance Ministry’s efforts to balance the budget, there is a risk of severe disruptions in 2024. In particular, revenue forecasts could turn out to be excessively optimistic for the oil-and-gas sector and other linked industries.

No guarantee of high oil prices

The latest indications are that European central banks are about to begin cutting interest rates – but we are not there yet. If high rates persist, there is a slowdown in Western economies, and a slower than expected recovery in China, the price of crude ($85 per barrel) used to calculate the 2024 Russian budget might prove to be optimistic. Indeed, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) projection of $82.6 in its latest report is lower. At the start of December, oil dipped below $75. Indeed, in November, Russia's oil-and-gas revenues dropped 17% compared with the previous month, hitting their lowest level since July. That won’t have much impact on the budget this year. But if prices remain where they are for any length of time, the Kremlin is in for a bumpy ride.

Russia’s budget rules mean any fall in oil-and-gas revenues will be made up from the National Wealth Fund. But, even so, reduced oil-and-gas revenues will weaken the ruble, fuel inflation (and, therefore, the cost of servicing national debt) and likely push up interest rates (and, therefore, limit economic growth). If growth falls, it could lead to a drop in tax revenue from sectors of the economy not linked to oil and gas.

Uncertainty for business

Russian business was subject to a windfall tax (estimated to be worth 305 billion rubles) in 2023. And there’s a good chance the authorities will impose some kind of regular levy next year. Therefore, businesses have little incentive to show high turnovers. Indeed, business leaders have openly spoken of their willingness to pay higher taxes if this would result in a more predictable tax take.

Another source of uncertainty for business is creeping redistribution of assets. “This topic was raised at Putin’s November meeting with big business and apparently he promised there would be no review of the results of old privatizations,” said a lobbyist from a major company who heard about it from a meeting attendee. “However, the flow of cases has not dried up.”

Why the world should care

The Russian economy in 2024 will face an ongoing decline in labor productivity, falling profits in most industries outside the defense sector, and imbalances in fiscal policy. Overheating will oblige the Central Bank to maintain high interest rates, dampening economic activity.

Even if the war ends next year, it will be a Herculean task to get the economy back on a civilian footing. The more Russia is hooked on “military steroids,” the more painful the hangover. Unlike the 1980s, there will be no financial help from the West. Yet, paradoxically, despite all the difficulties ahead, there are no major threats to the economy in 2024. Of course, future generations will pay a heavy price for the current state of affairs – but this is the last thing on the Kremlin’s mind.

Further reading

Elements of an Eventual Russia-Ukraine Armistice and the Prospect for Regional Stability in Europe by Samuel Charap and Jeremy Shapiro

Russia Under Non-Military Pressures: Expectations, Realities, and Lessons of Sanctions by The European Center for Global Challenges

Putin’s End-of-Year Event Was a (Doomed) Invitation to Dialogue by Tatiana Stanovaya

Podcast: What’s the Secret of the Russian Economy’s Resilience? by Alexander Gabuev and Alexandra Prokopenko

The West’s Inaction Over Ukraine Risks Dangerous Conclusions in Moscow by Dara Massicot

Written by Alexandra Prokopenko and Alexander Kolyandr

Edited by Howard Amos, translated by Andy Potts

This is our last newsletter this year, and we will be taking a break over Christmas and New Year. We will resume normal service on Friday, Jan. 12.

Thank you for reading The Bell! We’d like to take this opportunity to wish you a happy festive period, and our best wishes for a prosperous and peaceful new year.