Russia’s 650,000 wartime emigres

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — written by Denis Kasyanchuk and Alexandra Prokopenko and brought to you by The Bell. Our top story is The Bell’s study into the exodus of Russians following the invasion of Ukraine. We also look at headaches for the Central Bank as it struggles to bring inflation under control.

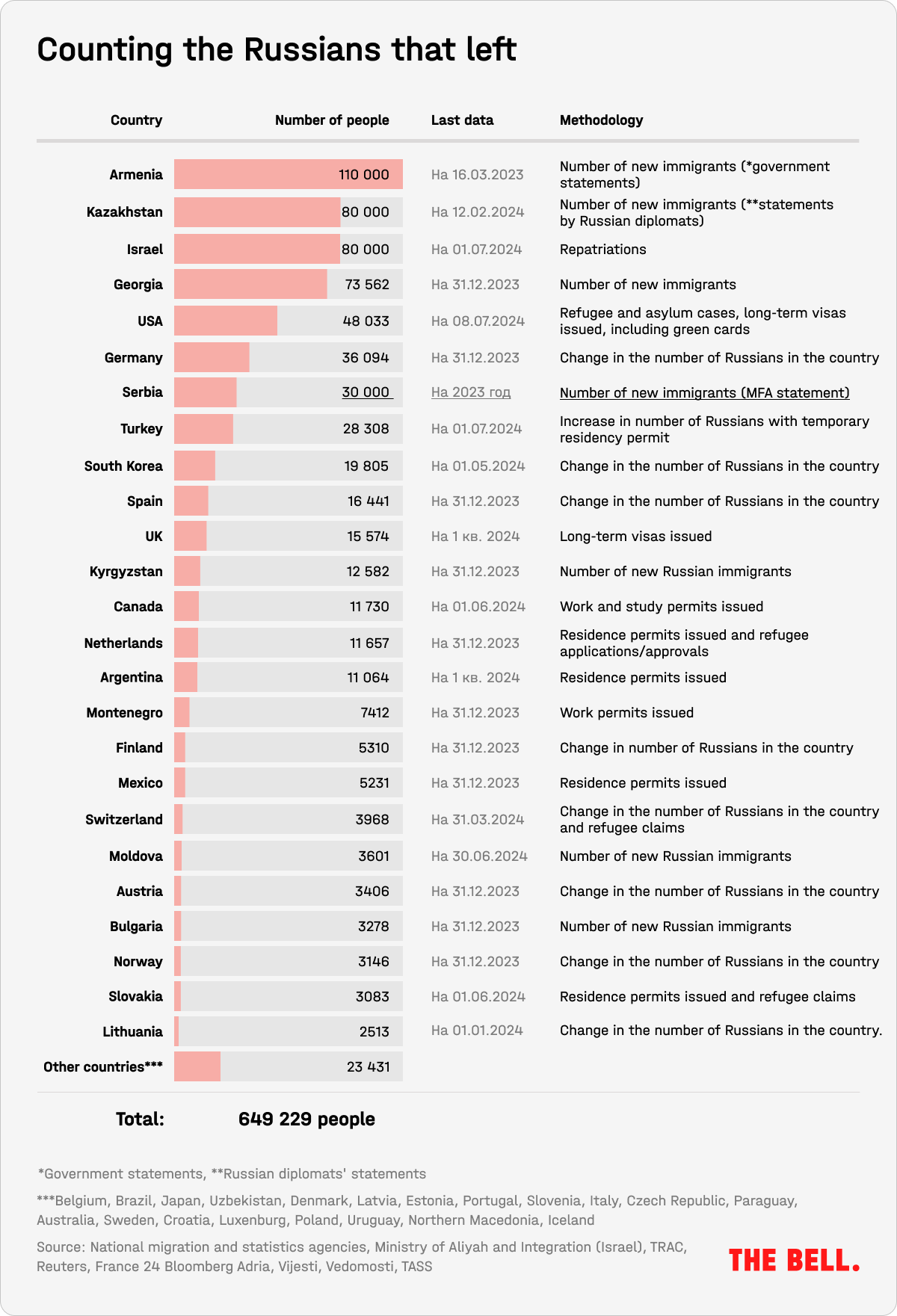

Around 650,000 Russians who fled after the invasion still abroad

The wave of people leaving Russia since February 2022 is the most significant exodus from the country in three decades, a new study by The Bell has shown. At least 650,000 people who left Russia after it invaded Ukraine are still abroad. They present a political and economic headache for the Kremlin, and their absence is increasing tensions in the labor market at home.

Where have they gone?

Russia itself has not disclosed how many people left the country after Feb. 24, 2022. The figures from the various agencies that publish immigration statistics do not reflect the true picture. For example, the oft-cited FSB border service figures show only the number of crossings of the Russian border, where one individual can account for multiple trips. Meanwhile the interior ministry’s statistics about the number of Russian citizens who have secured residency in another country only reflect those who both acquired the formal status and then voluntarily informed the Russian authorities — which far from everybody will have done.

To get a more accurate picture of how many Russians have permanently left the country over the last two and a half years, The Bell gathered data from around the world, contacting the migration services and statistics agencies of almost 70 countries to fill in the blanks. Combining all the public data, the answers to our requests and various statements by diplomats and officials, it emerged that since 2022, at least 650,000 people that left Russia have yet to return. That figure is 150,000 more than the rough estimates we made at the end of 2022.

The two biggest waves of emigration came in late February and early March 2022 — immediately after the invasion of Ukraine — and again in late September 2022 when President Vladimir Putin announced a partial mobilization, calling up 300,000 men to fight in Ukraine.

Not surprisingly, most of those who departed headed for neighboring former Soviet countries, where transport routes are easiest, Russian citizens can travel without visas, they can settle either without the need to apply for residency (or with only basic requirements) and many locals speak Russian. The most popular destinations were Armenia (110,000 Russian emigrants), Kazakhstan (80,000) and Georgia (74,000). In addition, more than 80,000 Russians repatriated to Israel. Taking into account all those issued long-term visas, green cards and asylum applications, the United States took in 48,000 Russians. Germany was the top EU destination, with 36,000 Russian migrants settling there. Another 30,000 went to Serbia.

These figures should be seen as a low estimate. Some countries did not respond to The Bell’s requests for information, including some that are known to be popular hubs for Russians who have left the country. For instance, the United Arab Emirates, Thailand, Indonesia, Azerbaijan and Greece did not reply, while the Cypriot migration and statistics agencies said they did not keep such data. Portugal has not published data for 2023. Most does not include people living in the country on tourist visas — which is possible for those settling long-term in some countries. In some countries in the Balkans and Central Asia, there are loose limits on how long you can spend in a country on a tourist visa, and any cap on the number of days can be reset by a so-called “visa run” — popping into a nearby country and returning on the same day. They are not captured by this data. On the other hand, some of the data that uses the number of residence permits issued would not reflect any Russians that had received permission to stay but then decided to return.

Who left?

Understanding who the Russians that left are and how they are integrating into their new countries is possible thanks to a series of regular surveys being carried out by a group of sociologists from European universities. Their data (the latest study is available here) shows that those who left Russia can be characterized as highly politicized, well-educated and in a better financial situation than the average Russian. They are typically young (aged 20-40) and 80% have university-level education. They are more likely to run their own businesses or work in white-collar roles such as IT, data analysis, sciences or the creative sector.

About a quarter either already speak the language of the country they moved to or plan to work hard to learn it. Two thirds of those who previously worked for Russian companies have left their old jobs and found new work with international or local firms. Before they left, 43% of respondents said they worked for Russian companies. By September 2022, just 17% were still employed by a Russian firm and by the Summer of 2023 that was down to 13%.

There are also some differences between those who emigrated at the start of the war and those who fled the partial mobilization drive. Those who left in February or March 2022, the first cohort, tend to be more affluent than those who left in September or October 2022, after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a major draft for the war. However, in terms of their socio-demographic terms or their experience or fear of political repression in Russia, there are only minor differences between the different cohorts.

In raw terms, the 650,000 who have left represent just 0.85% of Russia’s workforce. However, when the country faces a seriously limited supply of labor, this is a significant loss of young, highly talented and educated workers. One of Russia’s leading labor market economists, Rostislav Kapelyushnikov, believes that the labor shortage was first triggered by the Covid pandemic in 2020 and then accentuated by the war (or the “sanctions crisis,” as he calls it) with the waves of post-invasion emigration further stretching an already acute labor shortage.

Worsening the problem, the hundreds of thousands of those who left are among Russia’s most active and enterprising, now building businesses and careers abroad. This will have long-term consequences for Russia beyond just a deficit in the number of workers. It will make it harder for innovation to trickle through the economy and for productivity to increase, potentially hampering Russia’s economic potential for years to come.

It also creates yet more problems for Russia’s demographic crisis. Between 2012 and 2032 the number of people aged 20-39 is set to fall by around a third — or 13 million, while the number of over-60s will rise by 50%, estimates Salavat Abylkalikov, a demographer at the University of Northumbria in Britain. “The labor shortage will grow and grow until the early-to-mid 2030s and we are reinforcing this by driving young people out of the country.”

Headaches for the Kremlin

These emigrants present serious headaches for the Kremlin — both political and economic.

First, the September 2022 images of streams of people queuing for kilometers to cross into Georgia in a bid to escape mobilization undermined the narrative of a tight-knit nation united behind the invasion of Ukraine. Second, once abroad emigrants quickly united into communities with a focus on counteracting propaganda and promoting anti-war messages both to Russians back home and internationally, in an active attempt to dispel the narrative that all Russians support the war.

Irked by such campaigning and seen by some officials as traitors, Russian authorities and hardline officials and parliamentarians have repeatedly discussed the possibility of putting various restrictions and punishments on emigrants. Proposals have included confiscating their property, hiking taxes, stripping state awards, banning remote work and even a call for the FSB to investigate emigrants for “extremism” and “treason”.

Some of those plans have had an impact. State-backed companies have been limiting opportunities for their employees to work from home, forcing them into the office and, therefore, to stay in Russia. Putin said in Summer 2023 that “according to conservative estimates” half the Russians who left had now returned to the country. The Kremlin itself has, at times, softened its language against those who fled the country, to show they would be welcome to return. Putin said there was nothing wrong with people going abroad, describing it as “an extra element of connection” between Russia and the rest of the world.

Moscow likes to use every available opportunity to show that migrants are returning. As early as May 2022, Communications Minister Maksut Shadayev published data on the geolocation of SIM cards that he claimed showed 80% of those who left straight after the invasion of Ukraine had already returned. This spring Bloomberg reported on data from a Moscow-based corporate relocation firm, Finion, which suggested that 40-45% of those who left in 2022 had returned. The main reasons cited for repatriating were difficulties in securing residency abroad and trouble integrating. However, this data is unlikely to be representative of the wider picture, since only very select categories of the most affluent migrants use relocation companies.

Despite constant rumors, fears and speculation, the Kremlin has taken no real steps to target emigrants, or to restrict foreign travel. There has been no return of the exit visas that were required to leave the Soviet Union. The Kremlin likely feels similar systems used by the Soviet or East German authorities during the Cold War did more harm than good. Moreover, the Kremlin also seems to hope that, unlike during that period, Western countries are less willing to open their doors to Russian emigrants.

Why the world should care

Russian’s wartime emigrants are likely to enhance their new countries — both economically and demographically — and are willing to integrate. The boon to their new countries would be even more pronounced if bureaucratic challenges, like tough requirements to gain residency or difficulties opening bank accounts, were lessened. Western policies should seek to encourage such migration, which has a double benefit — attracting highly-skilled young workers and delivering a blow to the Kremlin.

Interest rates set to rise

A week before the central bank meets to decide whether — and by how much — to raise interest rates, the Central Bank has admitted that it needs to do something to tackle stubborn price rises. Markets have priced in a rate hike on July 26, the bank’s next policy meeting.

- Inflation accelerated sharply between May and July, as have signs that the price rises are stickier than previously hoped and the population’s inflation expectations, the Bank wrote in a recent analytical report. The regulator admitted that interest rates in the real economy are also rising, reflecting increased inflation expectations and belief that the bank will raise rates. That comes against a backdrop of increased economic activity — that the bank has warned is overheating.

- The Bank admitted that it would need tighter monetary policy for a longer period of time to bring inflation back to the official 4% target. At the very least, rates would have to remain elevated until the end of 2024. In other words, the current rate — already 16% — is not high enough.

- The main driver of high inflation is strong domestic demand, which outstrips any scope for enhanced supply or productivity gains. In its last report on inflation, the Bank estimated June inflation was running at 9.3% on a seasonally adjusted annual rate. That was down from 10.7% in May on the same measure, but remains far higher than during the first four months of the year.

Why the world should care

The Russian economy is still overheating thanks to high government spending and labor shortages pushing wages higher. The Central Bank admits that not only are rates likely to go up, but that they might not come down for a long time. The problem is that since growth is primarily being driven by government expenditure — which is less swayed by interest rates — tough monetary policy can’t do much to cool the economy.

Figures of the week

Just as the central bank is preparing to hike, inflation figures have shown a slight slowdown for the first time in six months. Weekly inflation slowed from 0.27% to 0.11% from July 9-15, per Rosstat data. Annual inflation also dropped from 9.25% to 9.21%, according to the economy ministry. As usual for this time of year, the most notable reduction was in food prices, but there was also a slowdown in prices for air travel, construction materials and fuel, while prices for household goods also fell slightly. These figures may enable optimists to hope that inflation has reached its peak, but a single week is hardly indicative of a change in trends.

The threat of secondary US sanctions continues to put pressure on Russian imports, pushing Moscow’s current account surplus higher in the process. The surplus for the second quarter of 2024 was more than double that posted for the same period of last year. The increase – from $8 billion to $18 billion – was bolstered by a decline in imports, according to central bank data. Year-on-year imports were down 8% (after a 10% decline in the first quarter), amid difficulties with logistics and payments.

In Moscow, Russia’s biggest real estate market, the number of mortgages struck in June 2024 was down one quarter versus June 2023, according to government data. Over the past six months, Moscow has seen a 10.7% fall in the number of mortgages issued compared with the same period last year, mostly due to a fall in transactions on the secondary market.

The Yuanization of international trade returned in June — but the Chinese currency is still yet to reach even one-tenth of the US dollar’s role in international transactions, data from SWIFT showed. Most likely, the yuan’s share is increasing because it is the leading candidate for financial settlements outside of the SWIFT network. The share of the Chinese yuan in global international payments rose to 4.61% in June, up 0.14 percentage points on May, posting its first monthly rise in three months.

The U.S. dollar was used for 47.08% of transactions (down 0.81 percentage points) and the euro for 22.72% (down 0.13 points). British sterling, meanwhile, saw its share up 0.24 percentage points to 7.08%. In terms of trade financing, the yuan overtook the euro for the first time since the start of the year to become the second most used currency. The yuan’s share of the market was up from 5.08% to 5.99%, while the dollar slipped by more than one percentage point to 83.15%.

Further reading

Putin’s Russia Will Continue to Pursue Nuclear Escalation

Is Iran’s Pro-Reform President a Threat to Russia-Iran Ties?

Political Newbie Stoianoglo Adds Intrigue to Moldovan Elections