Russia’s big sanctions workaround

Hello! This is your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. Our main story is an analysis of customs data that reveals how Russia is getting around Western sanctions by importing restricted goods via third countries. We also look at why, contrary to expectations, there’s been no wave of nationalization of Western business since high-profile seizures earlier this summer.

Western sanctions ineffective as Russia ramps up imports from third countries

President Vladimir Putin likes to boast about how Russia nullified Western sanctions on high-tech goods designed to limit Russia’s military production. At the Valdai Club gathering Thursday he said: “Much of what we formerly imported from European countries has been blocked. But we have solved all these problems.” While some of Putin’s claims — for example, that Russia has started to make its own high-tech products — are simply false, it’s true that Russia has learnt how to evade Western sanctions by importing goods via third countries. The Bell looked at customs data to assess the scale of this workaround.

Getting around sanctions

A ban on high-tech exports to Russia was one of the pillars of Western sanctions imposed on Moscow last year as a result of its invasion of Ukraine. Sanctions on such high-tech goods were intended not only to harm the Russian economy, but to limit the Kremlin’s capacity to wage war. Russia was to be deprived of things like aviation parts, lenses, and electronic components — which are crucial in modern warfare.

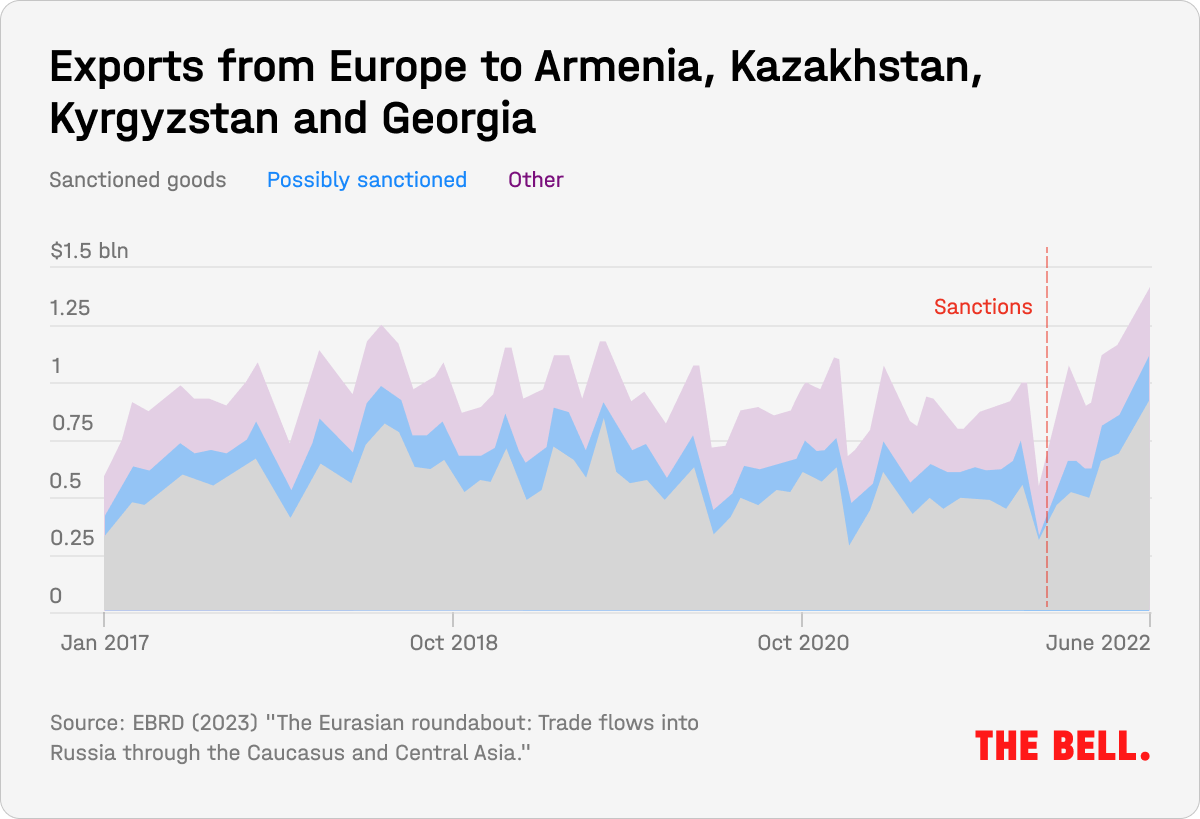

But there was no defense sector collapse. Russian companies quickly set-up new supply chains and started importing high-tech goods via third countries. Dozens of cases of Western goods finding their way to Russia have been reported in the media, along with evidence including names and documents. For example, Lithuanian firms sell aviation parts to Russia via the Central Asian state of Kyrgyzstan, U.S. microchips reach Russian military factories via Kazakhstan, and components used in the manufacture of cruise missiles are transported to Russia via Armenia in the South Caucasus.

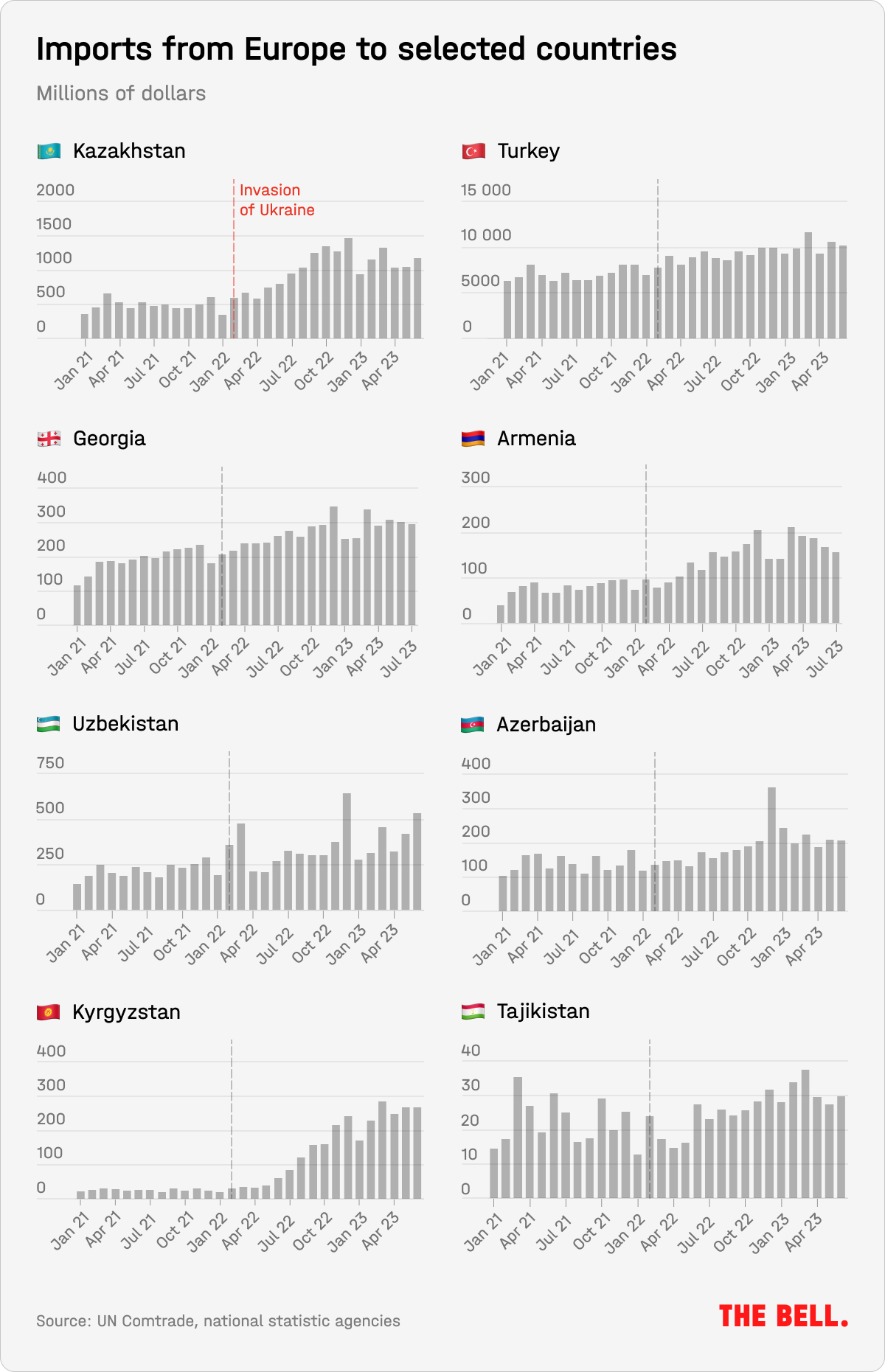

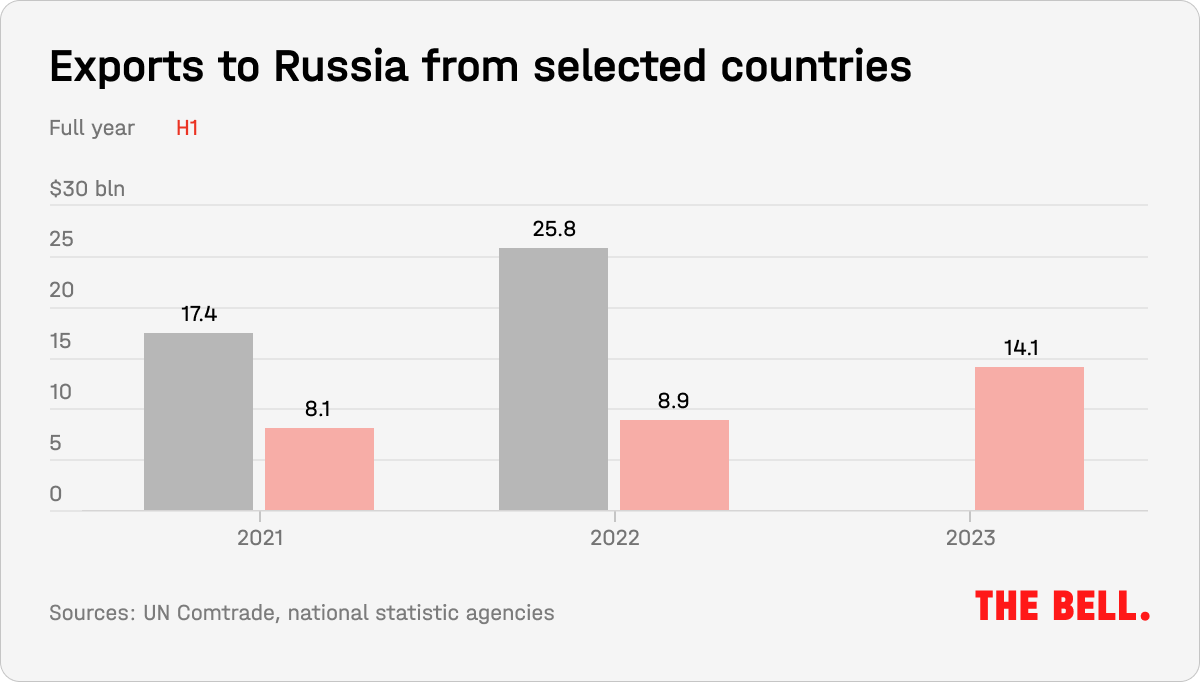

This major re-routing of trade is reflected in customs data. Between January and June, Russia increased imports from Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkey by a total of 37% (or $5.2 billion) compared to the equivalent period last year, according to The Bell’s calculations. And this correlates with a parallel increase in European exports to the same countries, which were up 22%.

How we made the calculations

Russia stopped publishing customs statistics shortly after the start of the war in Ukraine. But we can get around this by using export statistics resed by other countries.

For this analysis, we studied data on exports to Russia from Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkey. We used both official figures from these countries and the United Nations’ Comtrade international trade database.

We got information on European exports from Eurostat, the European Union’s official statistics agency.

The final figures may contain discrepancies as numbers for exports from one country and imports into another do not always match up (due to differences in methodology).

The war in Ukraine and sanctions reduced EU exports to Russia to $59 billion last year, their lowest level for 18 years. Russia’s total share of European trade dropped below 2%.

At the same time, however, EU countries have ramped up exports to countries with close ties to Russia. In 2022, the EU’s trade in goods to Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkey was up 24% year-on-year to $130 billion. In the first half of this year alone, it was worth $75.8 billion.

In 2021, the year before the start of the war, exports from Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkey to Russia amounted to $17.4 billion. In 2022, they reached $25.8 billion, a 33% increase.

What goods are being traded via third countries?

Eurostat data shows that, in 2022, the rising exports from Europe to Russia’s neighbors included several distinct types of goods: for example, telecoms equipment, microelectronics, transport technology, and electronic equipment for data processing (computers, servers, hard disks, smartphones, computer peripherals).

The fact that Russia’s neighbors have increased imports of sanctioned goods from Europe indicates that Russia is bypassing EU restrictions, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) wrote in a February report looking at import flows from Armenia, Kazakhstan, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan.

However, the EBRD authors pointed out that these trade volumes replace only about 5% of the imports Russia lost because of sanctions. The Bank of Finland has reached a similar conclusion: while re-routed goods have gone some way to mitigating the effect of Western sanctions, Russia has still not replaced all lost volumes in this fashion.

Some European countries have restructured their trade flows more than others since the imposition of sanctions on Russia, according to Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance. Primarily, these are Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Poland, which simultaneously reduced exports to Russia and exported more to Central Asia. “It is obvious that businesses are looking for ways to deliver their products to Russian customers. If direct exports are difficult, it chooses indirect routes,” wrote Brooks.

Why the world should care

Some experts are calling for sanctions to be tightened to close these loopholes. Economists from the Kyiv School of Economics and the Yermak-McFaul Group suggested in a recent report that the West should boost restrictions on Russian banks, expand a list of sanctioned goods to include “substitutes” for banned items, and introduce secondary sanctions to prevent third countries from re-exporting certain goods to Russia.

Russia’s expected nationalization of Western business has not materialized

Western companies in Russia were thrown into confusion by the July nationalization of the Russian assets of French dairy producer Danone and the Baltika brewery owned by Denmark's Carlsberg. But they have gradually come to terms with the developments, and Carlsberg this week wrote down the entire value of its Russian business. Admittedly, the Russian government continues to make it harder for Western companies to exit the Russian market — but no full-scale nationalization drive has followed the seizure of Carlsberg and Danone. Three months on, they’re the exception rather than the rule.

- “We have now concluded that we currently see no path to a negotiated solution for exiting Russia. We refuse to be forced into a deal on unacceptable terms, justifying the illegitimate takeover of our business in Russia… As a result, we will fully impair the value of our business in Russia,” Carlsberg said in a Tuesday statement.

- The initial shock of the Kremlin’s nationalization of the Baltika brewery has worn off and Carlsberg is trying to stop Baltika from selling beer in Russia under its brand names: Carlsberg, Tuborg Green and Kronenbourg 1664 (three of the five most popular beers in Russia). In its statement, Carlsberg said it was terminating agreements allowing the local subsidiary to sell the company’s products. Baltika is trying to dispute this decision in a Russian court while also hedging its bets by registering alternative brand names: “Greenbeat” instead of Tuborg Green and “Krone Blanche” instead of Kronenbourg 1664.

- The most intriguing part of the Carlsberg statement was that the company “refuses to be forced into a deal on unacceptable terms, justifying the illegitimate takeover of our business in Russia.” They seem to be hinting that, even after the Kremlin ordered the nationalization of the company, Carlsberg received an offer from a buyer. Perhaps they were referring to an offer from Taimiraz Bolloyev, a longstanding acquaintance of President Vladimir Putin and the former head of the Baltika that was reported by The Financial Times. Bolloyev was handed control of Baltika after the nationalization.

- The story of Carlsberg and Baltika suggests that the Russian authorities do not see such takeovers — when external managers are appointed on an order from Putin — as true nationalization. Perhaps they see it more as a mirror image of the Russian Central Bank reserves frozen in Europe — where the money has been seized but no-one yet dares to unfreeze the cash and hand it to Ukraine.

Why the world should care

It’s clear that nationalizing Western companies has not become a new trend in Russia. The only nationalization that has happened on Putin’s orders since Danone and Carlsberg was the nationalization last month of the printing house of Norwegian firm Amedia, which was used to publish now-shuttered independent media outlet Novaya Gazeta. This was a purely political decision. At the same time, several Western companies — including Carlsberg’s rival Heineken — have even managed to exit Russia.

Figures of the week

- Putin promised that the budget deficit this year will only be 1 percent (according to the government’s plans it was to be 2 percent).

- The source of Putin’s confidence is likely the rising price of crude, which is boosting Russia’s revenue. In August, the government’s income from energy exports rose 15 percent month-on-month. However, to get a proper grip on the budget, Russia needs to be able to control spending.

- The amount of cash held by Russians fell to 21.6 billion rubles in September — the first fall since spring 2022 that is not explained by seasonal factors, according to media outlet RBC. Experts explained the numbers as due to high interest rates and the end of the vacation season — but they said it was not a new trend.

Further reading

Why Russia and North Korea are dangling the threat of military co-operation

Our regular contributor Alexandra Prokopenko and political scientist Nikolai Petrov give their takes on the new class of asset owners created by Putin's deprivatization

How Russian officials who hoped for quick career advancement in Russia-controlled Ukraine have been left deeply disappointed