Secondary sanctions & Russia’s falling imports

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — written by Denis Kasyanchuk and brought to you by The Bell. This week our top story is an analysis of how U.S. secondary sanctions introduced last year have contributed to a significant fall in Russian imports. We also look at the possibility of more tit-for-tat nationalizations between the West and Russia.

Fear of U.S secondary sanctions hits Russian imports

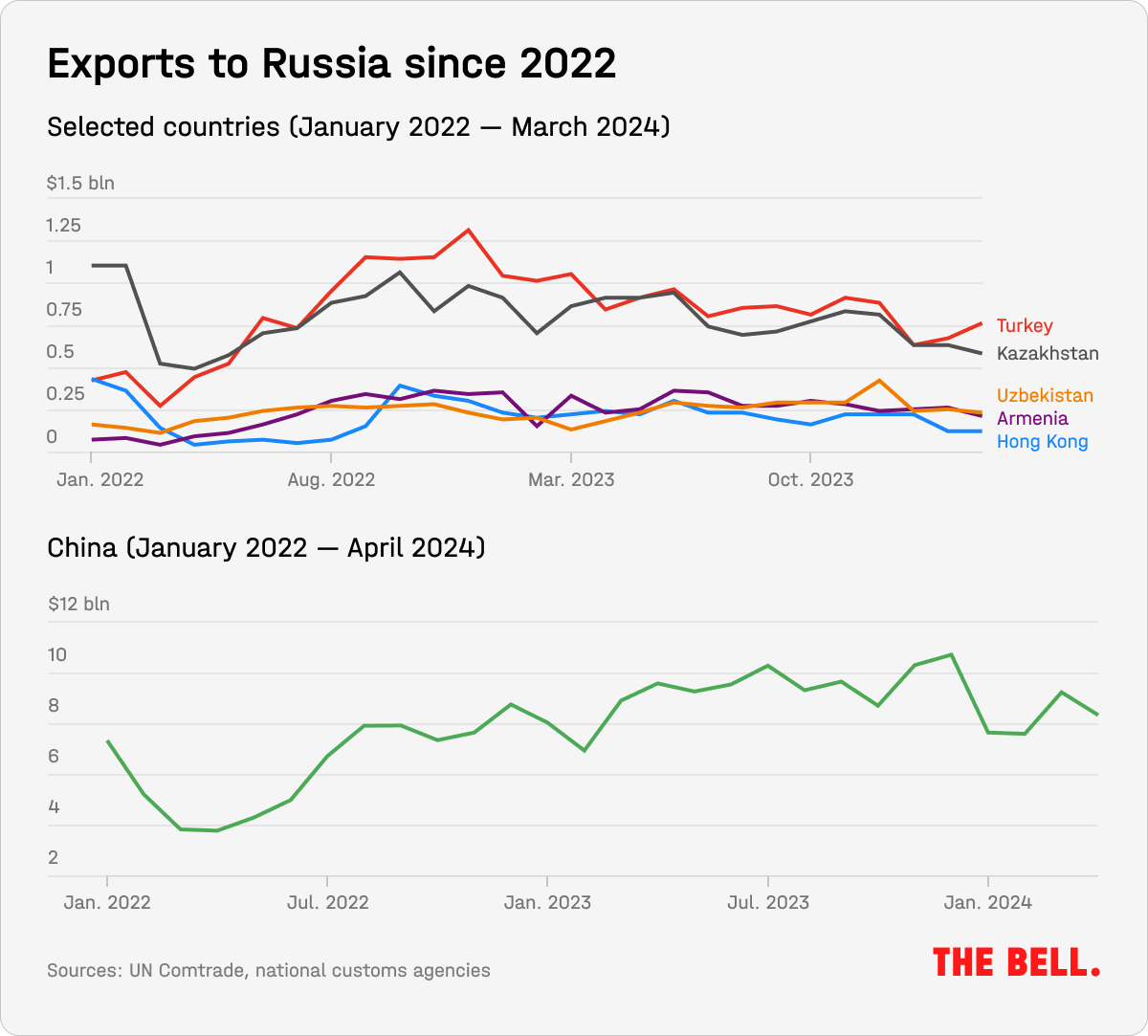

For most of the first two years of the war in Ukraine, Russia managed to evade one of the West’s main sanctions: a ban on high tech imports. Russian importers redirected trade via neighboring, or friendly, countries. But in late 2023 the U.S. threw a spanner in the works. When the U.S. started to threaten secondary sanctions against banks in third countries who facilitate banned trading, it disrupted Russian payments chains involving banks in China, Turkey, the UAE, and other intermediary countries. We looked at customs statistics to assess the impact on the flow of high tech goods into Russia – and found that it was significant. Since the start of 2024, imports from some countries are down a third.

What’s going on?

After the imposition of Western sanctions on high-tech imports, Russia importers adapted, and started buying goods from neighboring countries — particularly Kazakhstan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkey. At the same time, foreign trade statistics for those countries showed a spike in imports from the U.S. and Europe. In effect, they became channels through which Russia acquired sanctioned goods. China played a similar role.

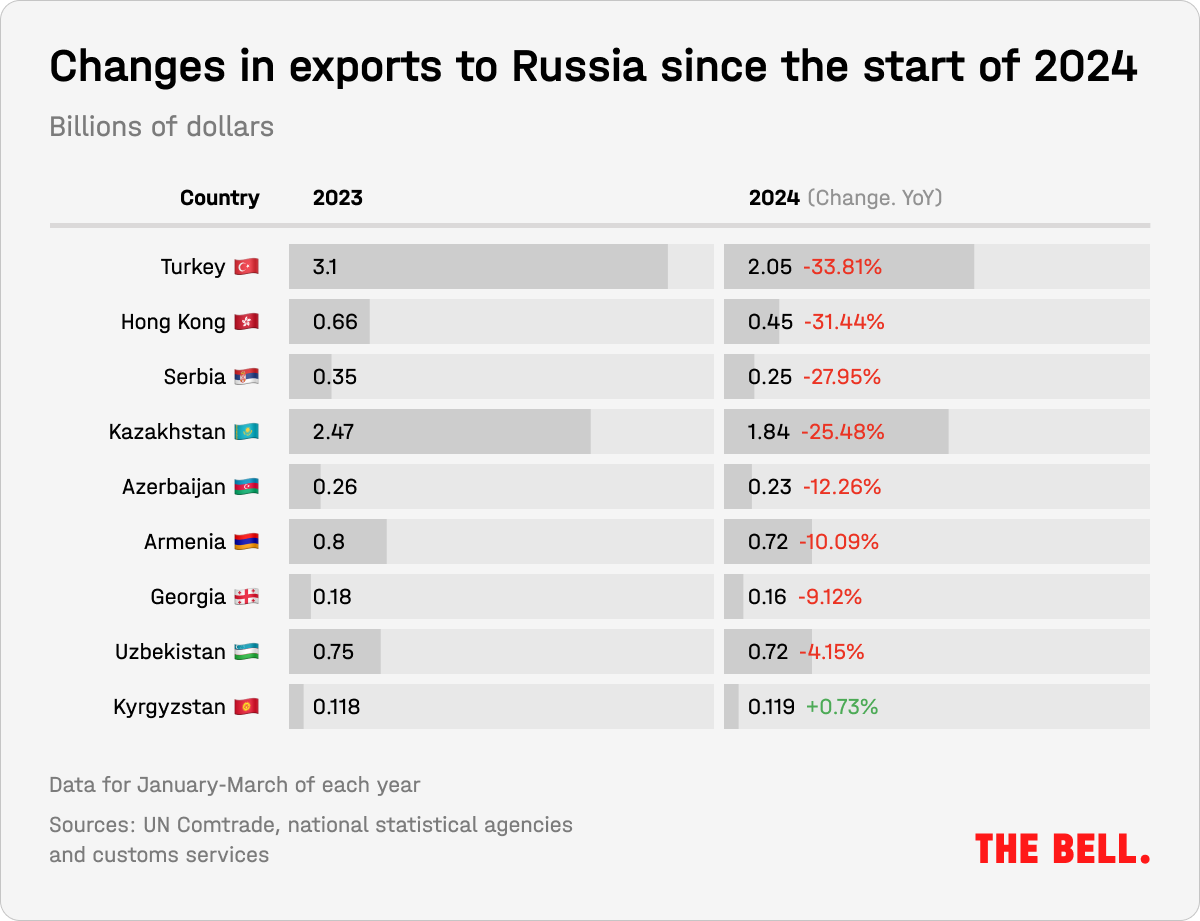

However, with the U.S. threatening secondary sanctions in late 2023, Russian importers encountered payment problems. Customs data shows that, as a result, first quarter 2024 data for imports to Russia from some of its biggest trading partners fell by about a third. The biggest drop was in imports from Turkey, Hong Kong, Serbia and Kazakhstan.

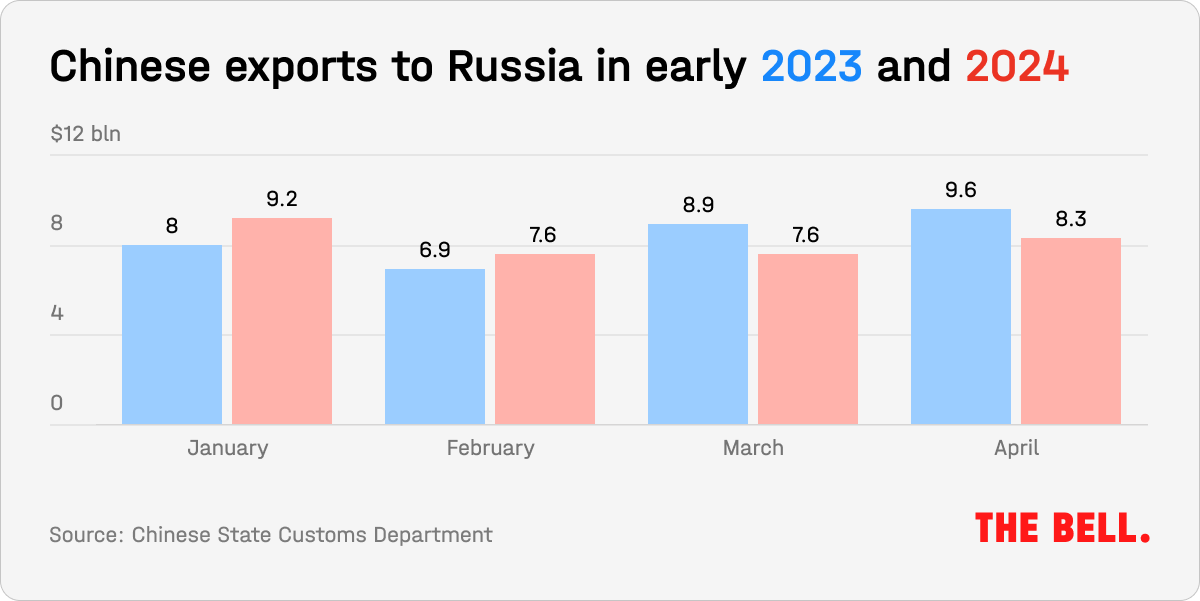

Imports from China, Russia’s main trading partner, also declined. Over the first four months of 2024, Chinese exports to Russia dropped 2% (in 2023, for comparison, they rose 46.9%). In cash terms, that 2% amounts to more than half a billion dollars. Moreover, the monthly dynamics show a downward trend. In January and February exports from China to Russia were up 12.5%. In March they fell by 14.2% and in April by a further 13%.

Kyrgyzstan was the sole exception – in the first three months of 2024, exports to Russia from this Central Asian country rose 0.73%. However, this is not particularly surprising given the pro-Russian course that Kyrgyz President Sadyr Zhaparov has followed since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, according to expert Temur Umarov. “Kyrgyzstan now could be called one of Russia’s most loyal backers in Central Asia; it is not afraid of secondary western sanctions on its businesses or financial institutions,” said Umarov.

Payment problems

Biden’s decree last year authorized the U.S. to impose sanctions on any bank that helped Russia evade sanctions on the import of items essential for the defense sector. Up to now, no such sanction has been introduced, but just the possibility has been enough to seriously worry many financial institutions. The U.S. is making strenuous efforts to ensure it is taken seriously: U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen has spent months touring the world – from China to Germany – to issue warnings about financing Russian imports.

As a result, Russian companies have faced serious problems making payments to foreign banks. Turkish banks have demanded additional checks, in and in Hong Kong there are stricter rules for working with Russian clients. In China, things are especially tricky. In some cases, it is taking six months to process payments through Chinese banks, sources told Reuters last month, and the more closely the goods in question look like potential military components, the more extensive the checks and delays. The threat of sanctions have also complicated payments in Chinese yuan – which the Kremlin had been relying on as a way of mitigating the effects of sanctions, and reducing risks.

Intimidation is a very effective way to pressure banks, said Elina Rybakova, a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, as banks are far more vulnerable than companies. “That difference allows the U.S. to apply pressure to banks without specific details. If you scare them, banks will withdraw not just one step from the red line, but a full half a kilometer.”

Leading Chinese banks have indeed begun to block transfers from Russia, an employee of a logistics company that imports goods from China confirmed to The Bell. However, according to him, the situation is not critical. “First, there are Chinese banks that have worked with Russia and continue to do so,” he said. “These banks, broadly speaking, are not in the top 20. Suppliers open accounts with them and send yuan from Russia. Second, many people use Turkey, the UAE or Kazakhstan and make payments through these countries."

The first four months of 2024 saw total Russian imports fall 10.3% year-on-year to $20.9 billion, according to Central Bank data.

As well as payment difficulties, other reasons for this trend, according to the bank, could be high interest rates, accumulated inventories and the weakness of the ruble.

Which industries are affected?

Deliveries of electronics, equipment and components to Russia are in decline. In particular, there’s less Turkish machinery and Chinese equipment reaching Russia. In the first three months of 2024 there was a 57% year-on-year fall in imports of “machinery, equipment, vehicles, instruments and apparatus” from Kazakhstan. There were similar falls from Hong Kong (32%) and Serbia (almost 50%), according to The Bell’s calculations.

Why the world should care

Some observers believe there is a risk of blowback from secondary sanctions that could affect markets that have nothing to do with Russia. But it is clear these sanctions are pushing Russia further into isolation, and will cause productivity issues over the long term. “Recent events show that sanctions can be an effective instrument if they are properly applied and observed,” said Heli Simola, senior economist at the Bank of Finland’s Institute of Developing Economies. “However, it’s obvious that compliance must be constantly monitored and improved as Russia keeps trying to find new workarounds.”

Russia and US prepare for tit-for-tat seizures

The EU looks set to agree to a proposal to use Russia’s reserves frozen in the West at the start of the war to raise $50 billion in support of Ukraine. In an apparent response, President Vladimir Putin signed a decree that authorizes the seizure of any U.S. assets in Russia.

- The EU gave official confirmation Tuesday to a plan to transfer the profits from its share of Russia’s frozen reserves (€210 billion out of about €260 billion) to aid Ukraine. This would likely raise between €3 billion and €4 billion a year.

- G7 finance ministers this week also debated a U.S. plan to use Russian reserves to finance a bigger aid package for Ukraine – up to $50 billion through 2025. While there is no talk of direct confiscation, the U.S. suggests frozen Russian reserves in Europe could be used as collateral for a large bond issue, either by the U.S. or by EU countries. The plan is to repay the debt using future income from Russian money. Unlike previous U.S. proposals, this plan has preliminary approval from Germany and a good chance of being adopted at the G7 summit next month.

- Amid all this, it’s hardly a coincidence that the Kremlin published a decree Thursday authorizing the confiscation of U.S. assets in Russia as compensation for U.S. seizures of Russian sovereign assets. On paper, this is a response to the law signed by U.S. President Joe Biden at the end of April to allow for the extrajudicial confiscation of Russian assets in the U.S. (although the U.S. controls a mere $5 billion of the Russian Central Bank’s total frozen reserves). Putin’s decree permits a retaliatory confiscation of U.S. assets in any jurisdiction “in relation to decisions taken by the U.S. government or legal authorities.”

- It looks a lot like the Kremlin is considering seizing privately-owned U.S. assets. Even in the third year of the war in Ukraine, such U.S. assets in Russia could be worth tens of billions of dollars. Several U.S. companies still have a presence in Russia, including oil firms ExxonMobil and Chevron, oil service companies Schlumberger and Weatherford, and GE industries. And there are a number of U.S. companies still operating in the Russian consumer market: Philip Morris International (assets worth $3.88 billion), Pepsico ($3.8 billion), Mars ($1.5 billion), P&G ($1.1 billion) and Mondelez (Russian profits of about $1 billion last year).

Why the world should care

Whatever the G7 summit decides next month, it looks like a new wave of tit-for-tat nationalization is looming between Russia and the West. U.S. companies that decided not to pull out of Russia after the full-scale invasion in 2022 look extremely unlikely to be rewarded by the Kremlin for their loyalty to the Russian market.

Figures of the Week

- Between May 14 and May 20, inflation increased 0.11% compared with 0.17% the week before. Annual inflation went up from 8.03% to 8.11%.

- At a board meeting on June 7, the Central Bank will consider raising rates to 17%, Central Bank Deputy Chairman Alexei Zabotkin warned this week. Banks are expecting an increase, and several large organizations have already raised rates on short- and medium-term deposit accounts.

- Alfa Group founder Mikhail Fridman this week became the first Russian billionaire to demand compensation for assets frozen in Europe. He wants Luxembourg to reimburse him $15.8 billion as part of pre-trial proceedings. If he is refused, Fridman plans to take the case to international arbitration.

- The number of VIP clients at Russian banks increased 1.5 times this year, according to calculations by consulting firm Frank RG. There were 17,700 wealthy clients (those with combined funds of 3.7 trillion rubles in Russian banks) and 4,100 very wealthy clients (with capital worth 9.4 trillion – this figure is up 68% from last year). The number of bank clients with capital of at least 100 billion rubles in Russian is up 50% from last year. In 2023, the capital of wealthy Russians grew thanks to high deposit rates, positive currency revaluation and stock market growth. But more than a third of the rise was due to a reduction in capital outflow.

Further reading

President Raisi’s Death Shows the Russia-Iran Partnership Is Inescapable