THE BELL WEEKLY: Russian ruble woes

Hello! This week, our main story is about the ruble's downturn amid Prigozhin’s mutiny. We also look at a new challenge for Russians in Germany, and we talk with demographer about whether Russia is dying out.

Russian ruble plummets amid Prigozhin rebellion

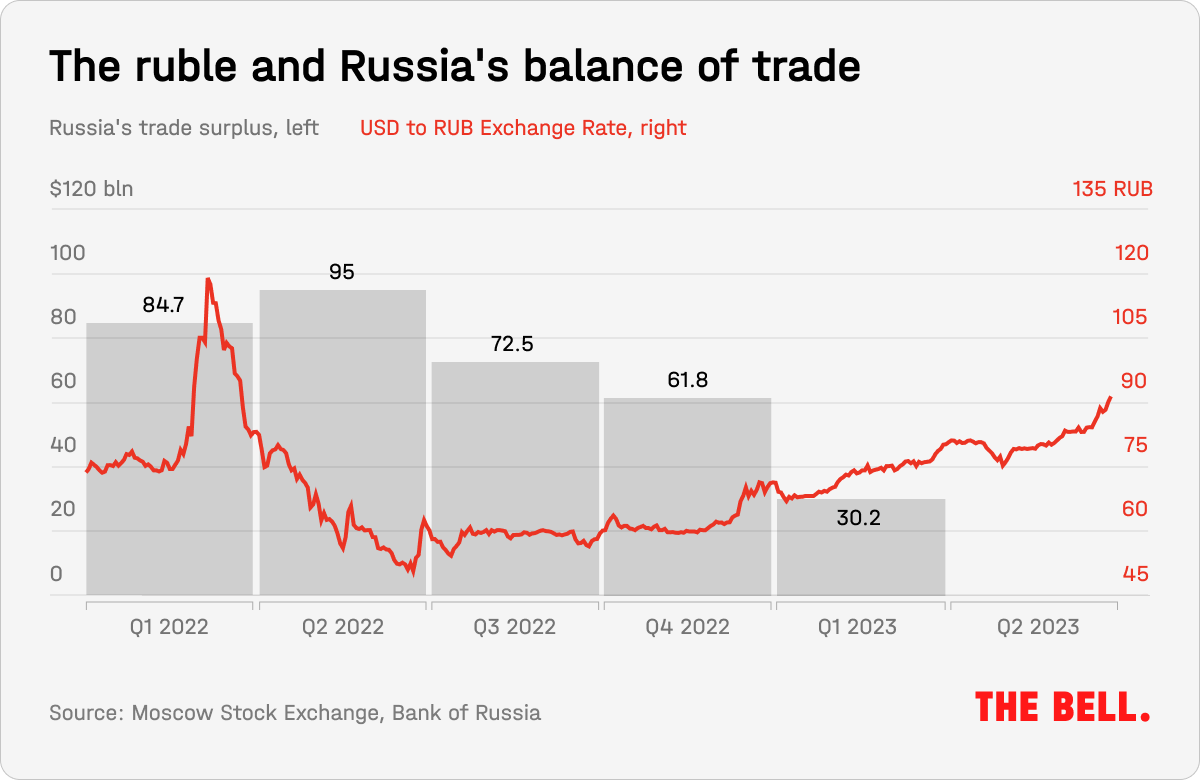

The Russian ruble has nose-dived in response to Yevgeny Prigozhin’s rebellion, accelerating its gradual depreciation since the end of last year. In the two weeks since June 24, the ruble fell 12% against the dollar and surpassed the symbolic 100 ruble per euro mark. The current exchange rates hark back to levels seen during the tumultuous early months of the war. The ruble's downturn was not unforeseen — throughout the preceding year, it was artificially inflated due to sanctions hampering imports while burgeoning oil prices boosted export revenues. However, reassuring the Russian people, who are used to assessing the state of the economy through the lens of exchange rates, remains challenging.

- In the two weeks from June 24 to July 7, the ruble experienced a dramatic fall. Against the dollar, it decreased from 84 to 91.2, and against the euro, it dropped from 91 to 100.3. At its nadir, one dollar cost 94 rubles and one euro was 102, the highest levels since March 2022, when the ruble was in freefall following the invasion of Ukraine. At that time, the government attempted to halt the slump using draconian currency controls.

- The ruble rebounded quickly in summer 2022 and reached a long-term high of 54 rubles to the dollar in November of that year. This resurgence had less to do with the state’s currency restrictions and more with the imbalance in Russian trade due to sanctions: rising oil prices inflated export values while trade embargoes dampened imports. In Q2 2022, Russia exported almost three times as much as it imported. However, as oil prices fell and Russian businesses discovered new ways to navigate trade restrictions, this imbalance began to level out, and the ruble started a steady devaluation — although nowhere near as rapid as in recent weeks.

- Prigozhin’s rebellion has triggered a new collapse for the ruble. Despite this, the fundamental factors remain the same: a shrinking trade surplus, capital outflow and an overall decline in the economic situation.

- As always, the ruble's fall will drive up prices for imported goods in Russia, particularly those not produced domestically, from smartphones and laptops to rum and whisky. Prices are likely to rise faster for goods arriving in Russia as “parallel imports” — a scheme introduced after Western sanctions that allows importers to bring in goods to Russia that were not originally intended for the country. We delve further into the implications of the ruble's collapse here.

Why the world should care

The ruble's depreciation exposes cracks in the Russian economy that President Vladimir Putin is keen to downplay. For Russians, this depreciation is an easy-to-understand indicator of economic health, as those who experienced the hyperinflation and currency crashes of the 1990s tend to closely monitor exchange rates and view them as an economic barometer.

The Bell is now listed as “a foreign agent” in Russia: our website is blocked, we can no longer raise money through advertising, and our business model is in ruins. Journalists in Russia face greater risks than ever before. Repressive new laws threaten up to 15 years in jail for objective reporting.

However, we are not about to give up. This newsletter is our newest project. It presents an in-depth analysis of the Russian economy, which has survived the first year of the war but is becoming ever more secretive. We will try and shed some light on what’s going on. Each edition will tackle a part of the big question: how long can the Russian economy endure under sanctions and when will the Kremlin run out of money for its war?

We don’t want to have to charge a fee for our newsletters. However, if The Bell is to continue its work, we need your support.

You can make a donation here. It will help our journalists continue investigating stories, breaking news and publishing newsletters.

Russian vehicles seized in Germany

A new challenge has arisen for Russians in Europe. Germany, a favored destination for Russians fleeing their home country, has started to arrest the vehicles of Russian immigrants. Although this measure is unlikely to have any direct impact those evading sanctions, it creates new hurdles for those who have the right to migrate to Europe.

- About a dozen Russian citizens have already encountered problems with having their cars arrested. These incidents have so far only been reported in Germany — up to now, EU countries bordering Russia have let them through without any issues. However, this suggests that similar risks could potentially apply in other countries and may extend beyond vehicles, the Russian independent media site Agentsvo reported. While owners can resort to legal recourse to recover their vehicles, the process is likely time-consuming and expensive.

- Russians residing in or traveling through Germany have witnessed their vehicles being seized. Ivan Koval, who lives in Hamburg with a German residence permit, had his car confiscated by customs officials from his home. Another individual, known only as Sergei, told the Fontanka news website that customs officials stopped him on the autobahn while he was travelling with his family. They unloaded his possessions from his car before towing it away.

- These reports first emerged in chat rooms serving the Russian community in Germany. However, the German authorities officially commented on the situation last week. “The importation of passenger cars from Russia to the EU is forbidden in accordance with Article 3i, Regulation 833/2014, which defines the embargo against Russia. In this context the expression ‘importation’ covers all movement of goods. The embargo does not imply any exemption from the ban in the circumstances specified,” the RBC newspaper reported, citing Germany’s customs directorate.

- The use of the word Einfuhr (import) in the German documents has caused controversy. This word covers not only commercial import as in the English version, but also temporary import with no intention to sell. The explanation from the customs service means that the latter is expressly prohibited. This is in line with EU practice, which allows each country to interpret and implement European sanctions on its own terms.

- In theory, many other items could be impounded in Germany using the same logic, including shoes, laptops and mobile phones. So far, however, there have been no reported cases of such items being confiscated.

Why the world should care

It’s clear that German customs’ newfound practice is a bureaucratic consequence of keeping to the letter of the law. It’s entirely likely these cases could be contested in court by demonstrating that the vehicles in question were imported for personal use. However, this places an additional burden on anti-war Russians looking to leave the country, with selling their cars becoming another item on their to-do list.

Is Russia dying out? Our interview with a demographer

Following the U.S.S.R.'s dissolution, Russia's population decline became an acute economic problem. Putin turned the "demographic solution" into his most important PR triumph. Yet the demographic crisis has resurfaced due to the pandemic and Ukraine's invasion. We spoke with demographer Salavat Abylkalikov about whether Russia is dying out, how fast, and why the country’s population is falling. Here are the top takeaways:

- In 2022, Russia's population growth rate was -0.38%. Assuming this rate persists, the population will halve in 184 years (according to Rosstat figures, Russia currently has 146.4 million inhabitants — The Bell). According to the UN's latest projection, Russia's population will be 112.2 million by 2100 under average circumstances.

- The Covid-19 pandemic caused life expectancy in Russia to fall by 3.3 years. It quickly began to recover in 2022, rising by 2.7 years. However, the war has disrupted this progress, and life expectancy is now impacted by war-related deaths and stress-induced substance abuse. Lower incomes and worsening access to medication, diagnostics, equipment and treatment are further reducing life expectancy.

- The war may also cause a decrease in inward migration, which has previously helped offset Russia's natural population decline. From 1992-2019, the natural loss was 13.8 million people, but inward migration compensated with 9.6 million. Russia could now find itself in a situation where natural and migratory losses reinforce one another.

- In the 1990s, after the lifting of the Iron Curtain, Russia went through a wave of emigration similar to that of the present day. There are several important differences between then and now, however. From a demographic perspective, the emigration of the 1990s was more than offset by a wave of immigration from the former Soviet republics — in 1994 alone, the net migration inflow was almost 1 million. But now emigration could be more short term. In the 1990s, people chose to leave, while today’s emigration has an element of escape. “For people like that, as soon as the situation changes, it’s likely that they will immediately start looking to book a return ticket.”

- Shifts in the age structure of the population pose a substantial demographic risk for Russia's economy. The generations born in the 1990s and 2000s, when Russia's birth rate was at its lowest, are now entering the labor market. This will exacerbate the existing crisis due to a lack of young workers. Meanwhile, the post-war generations of the 1950s and 60s are aging and approaching retirement.

You can read the full interview here.