The cost of a decade of confrontation

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. This week we try to come up with a rough balance sheet for what a decade of aggression toward Ukraine has cost Russia and the Russian economy. We also look at the West’s changing approach to Russia sanctions, and the possible consequences.

What an aggressive foreign policy toward Ukraine cost the Russian economy

Ten years ago this week, the first demonstrators assembled on Kyiv’s Maidan square to protest then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union. At the time, the event got little international attention – rather like the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Sarajevo in 1914. However, like that historic moment, the street protests in Kyiv would end up triggering a chain of events that had catastrophic consequences, including hundreds of thousands of deaths, millions of refugees, and the wholesale destruction of Ukrainian cities.

Of course, it was the Kremlin’s reaction to Maidan, rather than the protests themselves, which led to the violence. And, in addition to everything else, these events have also had immense economic repercussions. We tried to take a look at the economic pain Russia has inflicted on itself through ten years of aggression toward Ukraine.

A lost decade

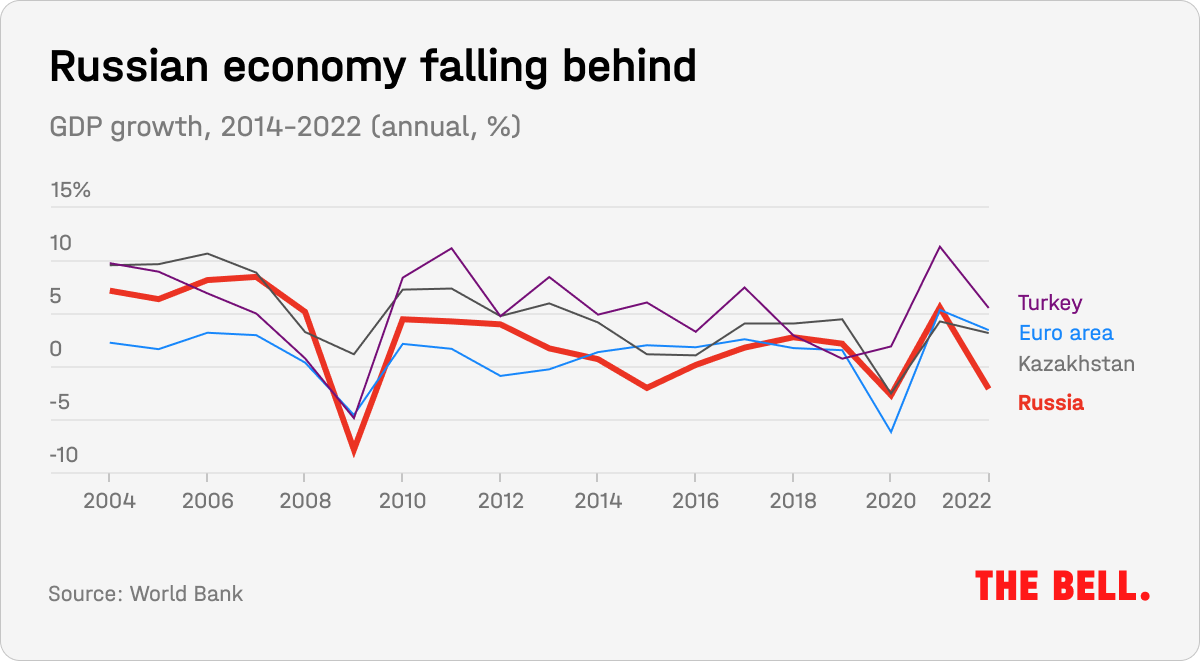

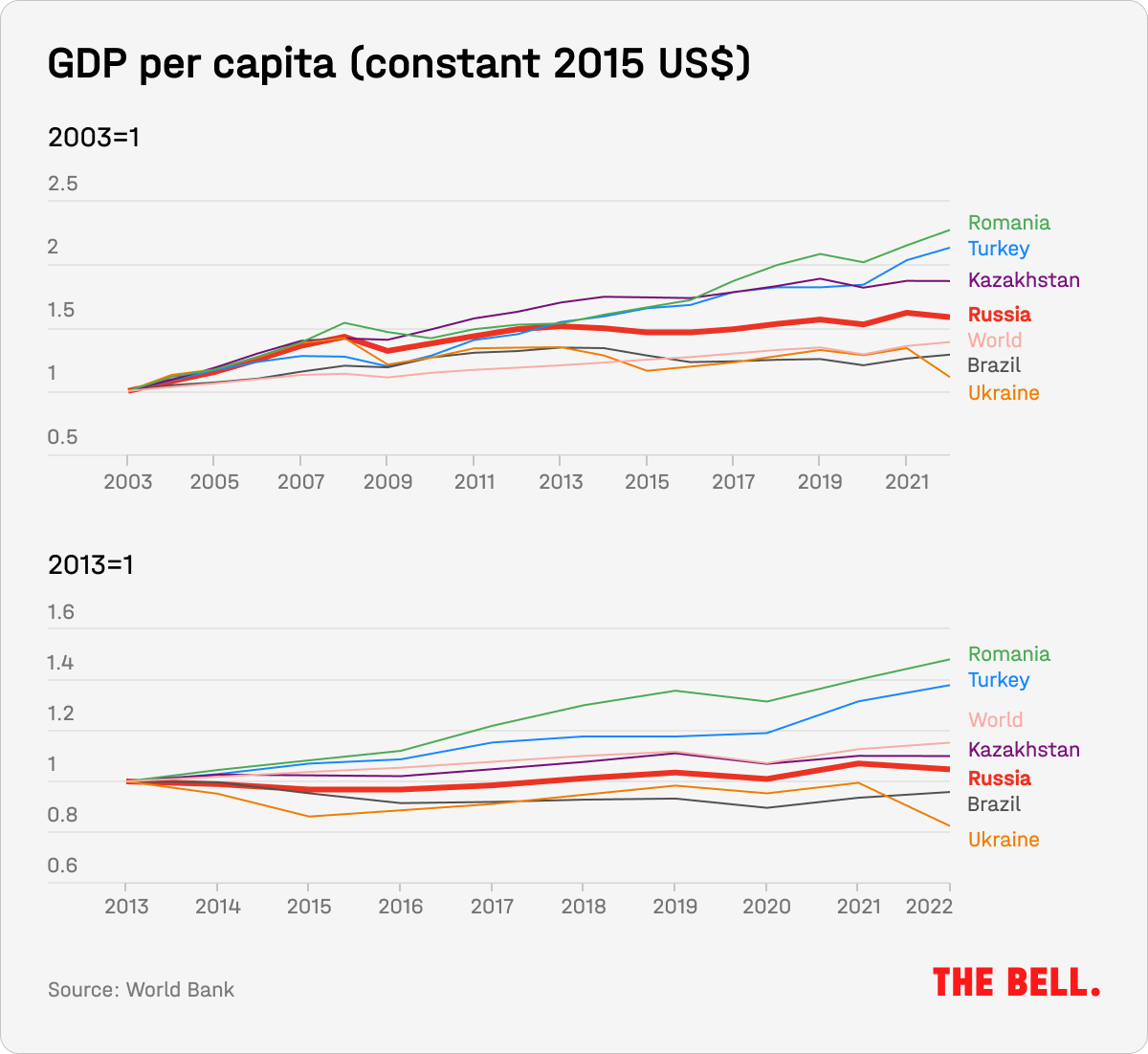

Russia’s economy has grown slower than the global average over the last ten years. Of course, this period also saw an oil price crash and the coronavirus pandemic. But the fundamental reason behind the underperformance was the Kremlin’s decision to pursue a confrontational foreign policy in regard to Ukraine.

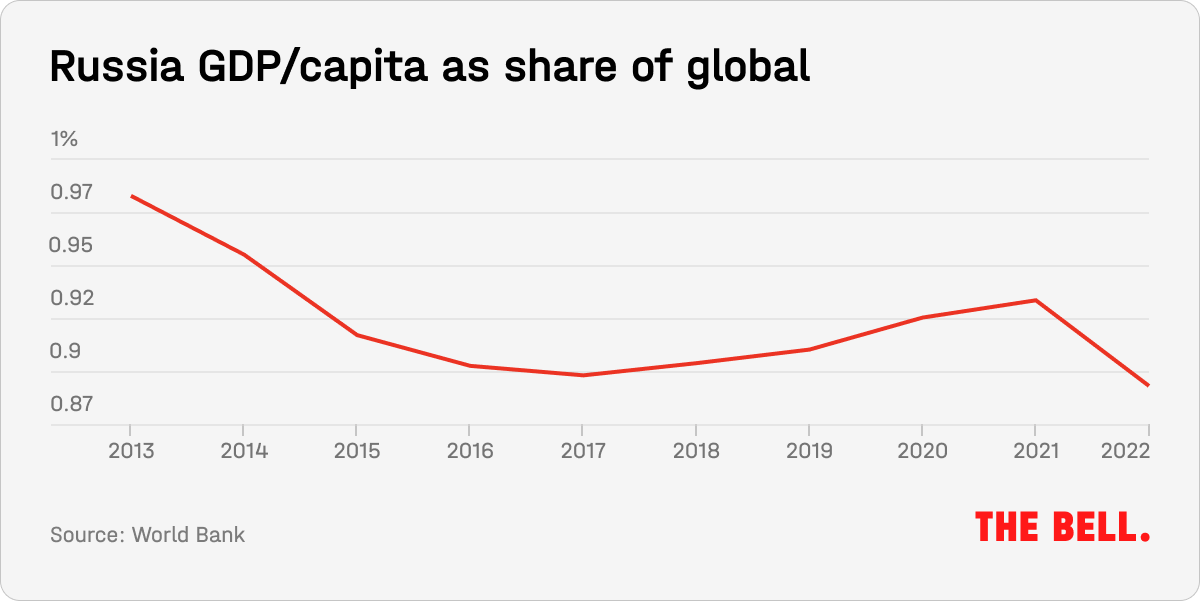

Since 2013, GDP per capita in Russia has increased 5%. That’s lower than the world average, and below that of most developing countries. Before Maidan, GDP per capita in Russia was just 2% below the global average; now this gap is five times as big.

As Russia was seizing the Black Sea peninsula of Crimea three months after Maidan began, a top official in the Russian government said in private conversation that Crimea’s annexation could cost the country about $20 billion. “It’s expensive, but it’s worth it because this is a once in a lifetime opportunity,” he said at the time.

Today, it’s clear the official was several orders of magnitude wide of the mark. We cannot here give a precise figure for Russia’s self-inflicted economic losses as a result of its aggressive policies toward Ukraine. First, this is an ongoing process, and second, such a topic is a more proper subject for an academic book. Nonetheless, we can make some rough estimates of the cost of satisfying Moscow’s imperial ambitions.

Direct costs

One of the first major costs was a $15 billion loan to Ukraine that was accepted by Yanukovych’s government in December 2013. Along with a significant discount on gas prices, this was supposed to ease the concerns of the Ukrainian population — and help bring an end to the protests on Maidan. However, when Yanukovych fled Ukraine in February 2014, Russia had only transferred about a fifth of what was promised. At the time, Putin said this was a fraternal loan for the Ukrainian people. But most of those people, like the wider world, interpreted the loan as a gesture of political support for Yanukovych’s regime. The loan, which took the form of $3 billion worth of Ukrainian Eurobonds purchased by Russia, remains a dead weight in Russia’s National Welfare Fund and is accounted for annually. However, it’s very unlikely ever to be recovered.If we exclude expenditure on weapons amid the current war, the most significant direct cost deriving from the Ukraine conflict relates to the annexation of Crimea. Almost 10 years after it was absorbed into Russia, the peninsula remains a huge drain on the economy. That’s not changing anytime soon, with Crimea among the 10 most subsidized regions of Russia. In July 2014, Russia’s Finance Ministry calculated that Russia would spend 90 billion rubles ($1 billion) a year on Crimea, plus a further 100 billion on developing the region. Eighteen months later, ex-Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin put the figure closer to 200 billion rubles a year, adding that Crimea was worth the money.

Russia annexed four more regions of Ukraine amid the full-scale invasion in 2022. They are also costing the Kremlin a lot of money. In 2023, they will receive 410 billion rubles from the budget in direct subsidies. Figures for overall spending on the occupied territories, including construction and roads, are not publicly available – and it’s hard to give a good estimate.

Indirect costs

Russia’s strategy of destabilizing Ukraine after the Feb. 2014 revolution, as well as the annexation of Crimea and backing for rebels in Eastern Ukraine led to Western sanctions. Now, Russia is the most sanctioned country in the world (most of them were imposed after the Kremlin launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022).

Nonetheless, even in summer 2014, the West sanctioned whole sectors of the Russian economy, as well as specific companies. In response, the Kremlin imposed a temporary ban on food imports from countries that supported the sanctions. Those temporary restrictions remain in force a decade later, and there’s no sign of them changing any time soon.

The 2014 sanctions made it impossible for several major state-owned Russian companies – Sberbank, VTB, Rosneft, Gazpromneft, Transneft – to take out long-term loans on the global capital market. Food prices, along with the “political” devaluation of the ruble from 2014 to 2016 saw annual inflation almost double.

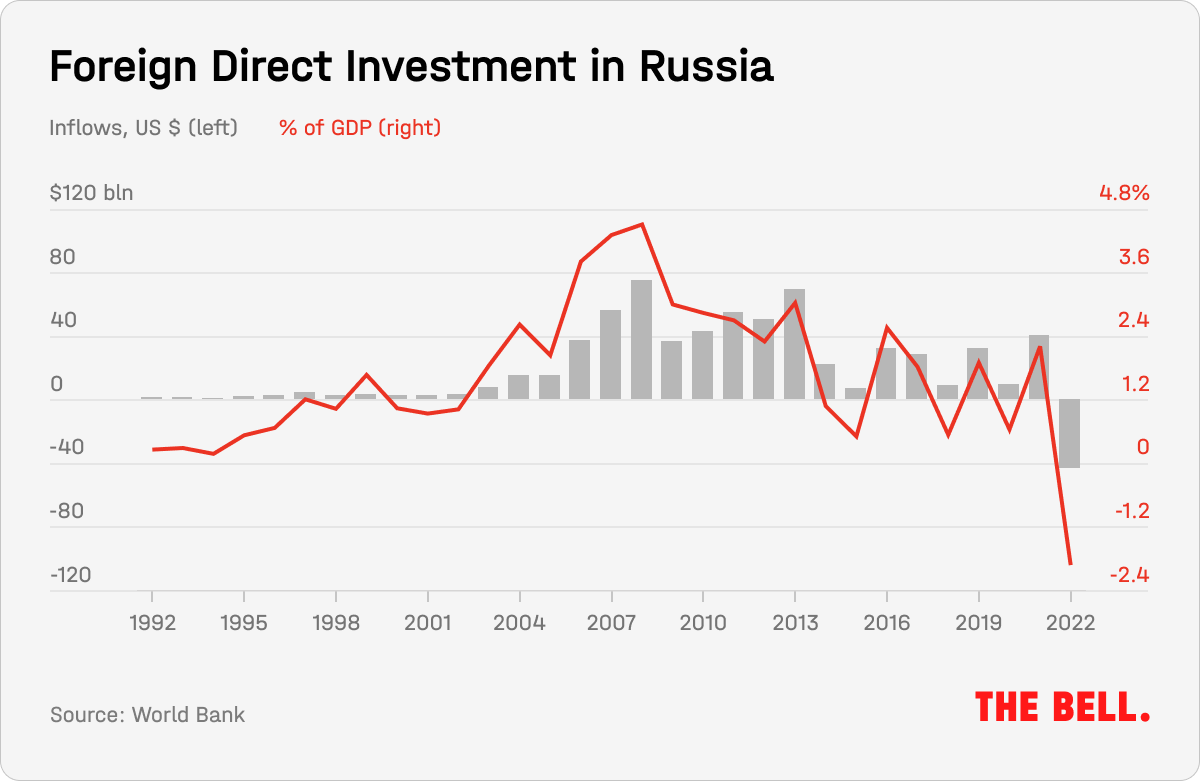

The full-scale invasion in 2022 added at least $300 billion to those losses when Russian state assets in the West were frozen as a part of sanctions. Direct foreign investment, which had been rising, fell into decline after 2013 and has never returned to its earlier levels – in either absolute terms, or relative to Russian GDP.

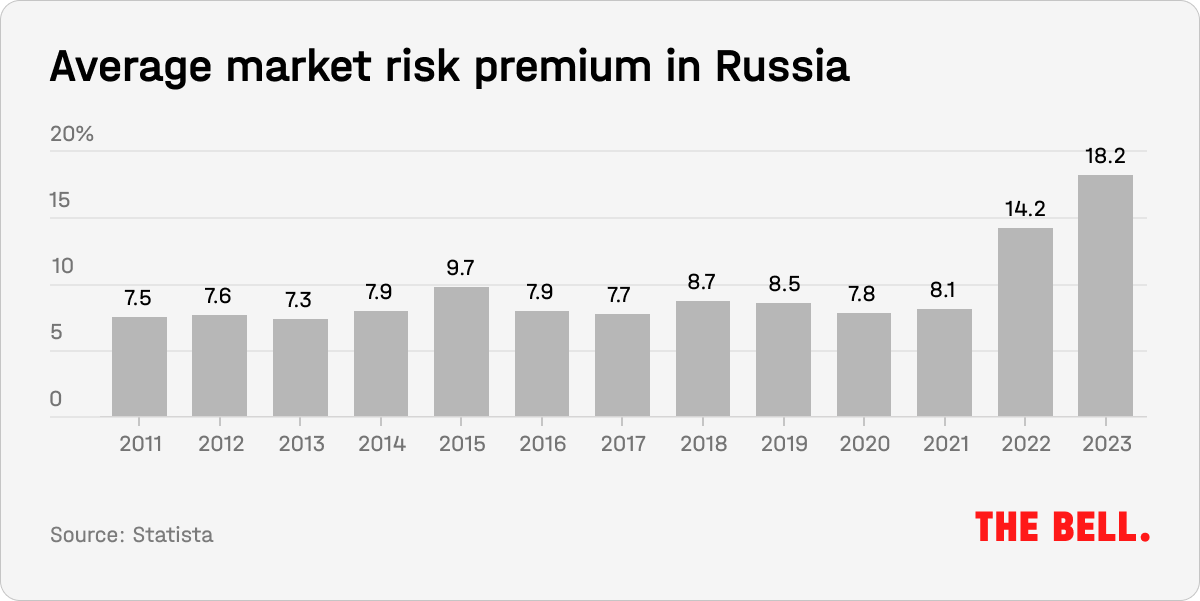

Sanctions, and especially the on-going risk of more sanctions to come, have raised Russia’s credit risk level, which is higher than before the annexation of Crimea.

The Kremlin’s confrontational strategy after Maidan, Western sanctions, and the fall in oil prices that coincided with the start of the political confrontation between Russia and the West, has also led to an increase in the state’s role in the economy and a concomitant deterioration of governance quality. Research by our contributor, analyst Alexandra Prokopenko, shows the Russian state is in a “perpetual crisis.” It increasingly adopts “manual controls” to the detriment of institutions and the rule of law.

Of course, the Ukrainian economy has suffered incomparably more from Russian aggression and the military attempt to occupy the country. However, decisions taken in the Kremlin have inflicted, and continue to inflict, significant economic damage on Russia itself.

Why the world should care

An accurate calculation of the costs of Moscow’s revanchist imperialism will be a task for another day. But it is crystal clear that the last decade of aggression, attack and occupation of Ukraine has meant significant economic losses for Russia – and the Russian people.

The West looks to close sanctions loopholes

It appears that the U.S. and its allies are increasingly revising their sanctions policy toward Russia. Now, the emphasis is on plugging loopholes in existing restrictions. This week, the spotlight was on financial institutions in the UAE and Cyprus, as well as Greek shipping.

- The publication of the Cyprus Papers, a huge quantity of Cypriot financial documents, highlighted the extensive use of financial companies and institutes on the island to circumvent sanctions against Russia. Their publication put pressure on the Cypriot authorities from the media, and Western politicians.

- According to Cyprus’ Philenews, an investigation into cases of sanction evasion against four Russian billionaires, including Alexei Mordashov, should be concluded within a month. But the issue does not end there. The Cypriot Police Force has created a special team within its economic crimes department to deal exclusively with cases involving sanction evasion. The team is currently investigating 12 cases.

- Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides told AP that he had requested additional investigative assistance from an unnamed third country. Given Cyprus’ long-standing connections to the UK, and London’s experience of investigating financial crime, it’s reasonable to assume this help will come from the UK.

- Three leading Greek shipping companies refused to transport Russian oil, Reuters reported Thursday. The companies are Minerva Marine, Thenamaris and TMS Tankers — between them, they have almost 100 tankers. The three have been transporting Russian oil for years and, unlike most European carriers, continued to do so up until the fall of 2023. This change of policy followed U.S. sanctions against Turkish and Emirati tanker owners who transported Russian oil.

- In the UAE, which is home to many companies trading in Russian oil, the authorities are tightening procedures for checking and monitoring organizations associated with Russia, Bloomberg reported, citing businessmen and consultants. Refusals to open accounts are becoming more frequent, and transfers are being subject to greater checks. Indeed, transactions can even be blocked until documentary evidence is provided and the origin of the funds can be confirmed. This affects the repatriation of funds to Russia.

- Immediately after the invasion of Ukraine, the UAE was welcoming to Russian clients. As a result, it attracted an inflow of wealth from rich Russians. However, in recent months the country’s authorities have set themselves the goal of getting off the Financial Action Task Force’s “gray list”. To do this, the UAE needs to tighten compliance with Western sanctions. At the same time, the U.S., EU and UK are increasing pressure on the Gulf State. Several local companies found themselves on the latest U.S. sanctions list after failing to comply with the Western price cap on Russian oil that was imposed last year.

Why the world should care

This looks like just the start of a change in sanctions tactics, with the West now seeking to pressure foreign governments. If this works, it will not, of course, end sanction evasion. However, costs for Russian companies will increase. As a consequence, the selling price for Russian oil may fall, and the cost of re-exporting goods to Russia may increase.

Figures of the week

This year’s budget deficit will be about 1% of GDP, compared with a projected 2%, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov said this week. According to the Electronic Budget portal, Russian budget revenues by Nov. 20 had amounted to 23.04 trillion rubles and expenditure stood at 25.68 trillion rubles. Thus, the deficit is 2.64 trillion rubles. Is the Finance Ministry planning to slow spending in the last six weeks of the year to get its desired result of 1%? If so, this may have a positive effect on both inflation, and the exchange rate.

Last week, annual inflation in Russia increased to 7.37%. At the same time, weekly inflation slowed: between Nov. 14 and Nov. 20 it was 0.2% versus 0.23% a week earlier.

Further reading

Permanent Crisis Mode: Why Russia’s Economy Has Been So Resilient against Sanctions

Russia’s Predetermined Elections Are Still Enough to Rattle the Elites

Living in an à la carte world: What European policymakers should learn from global public opinion