The unpredictable consequences of economic overheating

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — written by Denis Kasyanchuk and Alexandra Prokopenko and brought to you by The Bell. Our top story this time is an in-depth look at economic overheating in Russia. We also examine why inflation is so high, and why it is almost certain to lead to rate rises next month.

What are the dangers of Russian economic overheating?

The overheating of the Russian economy is now an accepted fact. Top officials including Central Bank head Elvira Nabilullina, and the head of state-owned banking giant Sberbank German Gref, talk about it openly. Increasingly, it’s only Russian President Vladimir Putin still championing Russia’s high growth as a major achievement without any awareness of the possible downsides. Despite efforts by the Central Bank – particularly high interest rates – it has proved extremely hard to effectively cool the economy. Everyone understands that overly rapid growth in wartime is dangerous, but what exactly is the threat?

What’s going on?

“If we try to drive faster than the car is designed to go, if we stamp on the gas with all our strength, sooner or later the engine will overheat and we won’t get far. The journey might be fast, but it won’t be long,” Nabiullina warned at the end of last year.

In short, overheating means that the economy is operating at its limits, and that productivity is not keeping pace with demand. It is invariably accompanied by rapid economic growth, which means, from the outside at least, it can often appear to be a good thing.

Economic growth in Russia is indeed continuing at a furious pace. Last year, Russian GDP expanded 3.6%, which was above the world average of 3.1%. And in the first quarter of this year, Russia’s economy grew as much as 5.4%. The World Bank has already had to twice upgrade Russian GDP growth forecasts for 2024 – from 1.3% to 2.2%, then to 2.9%.

Symptoms of overheating

There are many symptoms of an overheating economy. The IMF, for example, has nine indicators to determine overheating:

- Output relative to trend

- Output gap

- Unemployment and inflation levels

- External trade conditions

- Capital inflow

- Current account

- Increases in credit, property prices and share prices

- Extent to which the budget is balanced

- Real interest rates (rate minus inflation)

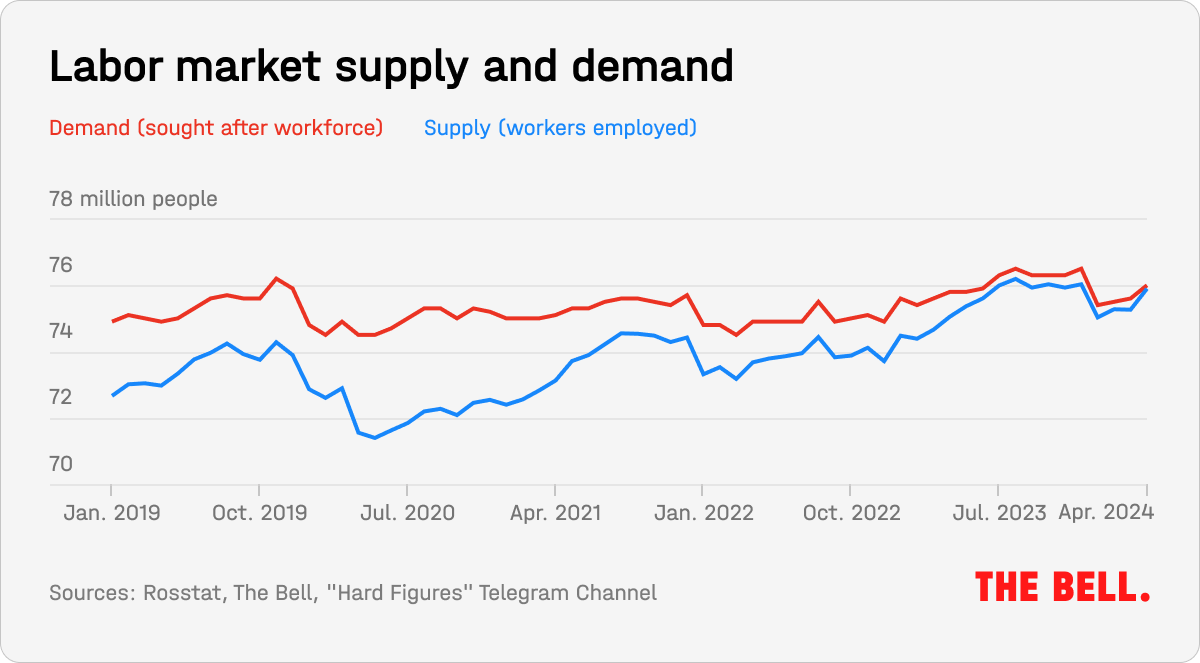

In Russia, the two primary indicators of overheating are inflation and labor shortages, according to the Central Bank. These two indicators are closely linked: high consumer demand pushes up prices. And that demand is fanned by uncontrolled wage increases (21.6% in March compared to the same month a year earlier). Wages are rising particularly fast in industrial regions with the biggest increases in Siberia’s Kurgan Region (+33%) that is home to the only factory in Russia manufacturing infantry combat vehicles.

“Overheating is linked to the unexpected restructuring of the economy: many companies left, many imports have stopped, many supply chains were destroyed,” said Alexei Kiselev, a researcher at the Florence School of Banking and Finance and a former employee of Sberbank’s Center for Macroeconomic Research. “Reduced competition in Russia has led to increased labor productivity, but this is not the kind of growth coming from technological progress or innovation in the delivery of goods or services.”

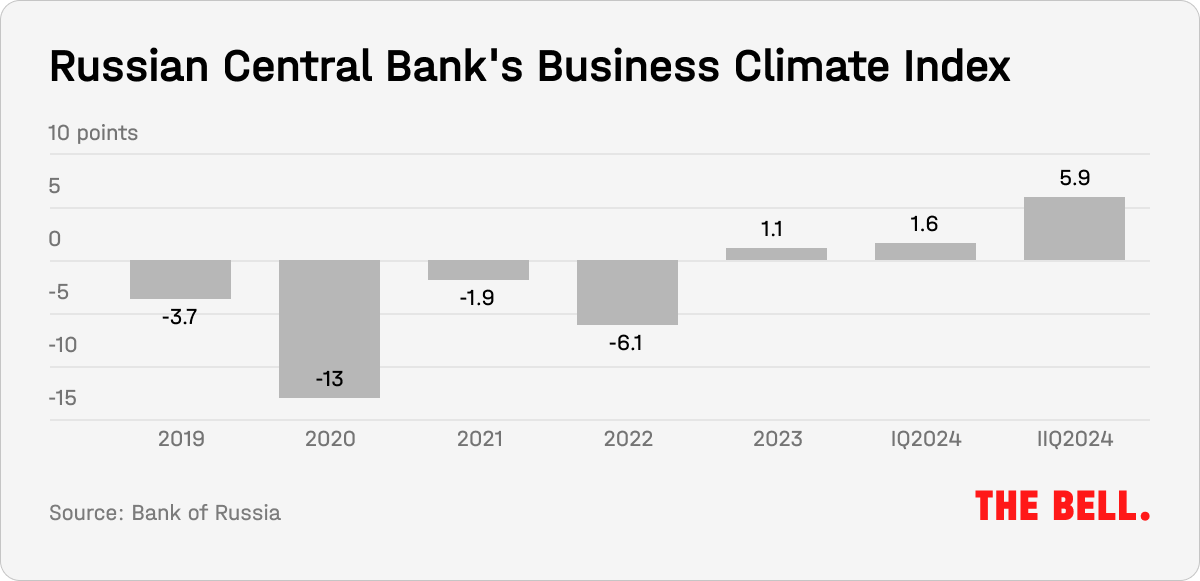

Another measure that can be used to gauge whether an economy is overheating is an assessment of the business climate. The higher this indicator, the more businesses are anticipating higher demand and productivity. In the second quarter of this year, the Central Bank’s assessment of the business climate hit a five-year high.

Nevertheless, there is no overheating of the credit market in Russia (at least not yet). “When it comes to lending, overheating usually entails excess risks where someone has gone overboard with their debt,” the chief economist of a Russian bank told The Bell. “The issuing of credit has not slowed down as much as the regulator would like, but the problem here is not with the credit itself.”

Why can’t the economy be cooled?

The main culprit for overheating is the state, which is spending record amounts amid the war in Ukraine. According to analysts from the Gaidar Institute, budget expenditures in 2022 and 2023 went up 17.2% and 14.2% respectively. That caused the share of government spending in Russia’s GDP to rise from 34.7% in 2021 to 36.6% in 2023.

In an attempt to cool the economy and stabilize inflation, which reached 8.6% at the end of June, the Central Bank has held interest rates at 16% for more than six months. Reports suggest some members of the Bank’s board of directors want to see further rises, perhaps up to 18%. This is approaching the 20% rate introduced at the start of the war in Ukraine (although it was quickly lowered). Analysts at most of Russia’s top banks anticipate that the Central Bank is going to raise interest rates in the coming months.

In theory, high rates should cool the economy – the higher interest rates, the more expensive it is to borrow (which dampens demand and inflation). Right now, though, this doesn’t seem to be happening. The reasons for this are a subject of disagreement.

Economist Georgy Zhirnov has suggested that the failure of high interest rates to impact the economy is down to high levels of “non-market” borrowing, especially state-subsidized mortgages. Many other economists agree. However, Zhirnov has also pointed out that, in the first half of this year, the volume of approved mortgages was down 60% on the equivalent period in the previous year. This suggests high interest rates are having an effect.

One Russian banker highlighted to The Bell that certain sectors of the economy are also receiving subsidized loans – particularly, agriculture and manufacturing. “We estimate the discount at 1.5-2 percentage points,” he said.

What happens next?

There is no clear consensus about what might happen when the economy stops overheating. Many have walked back more dramatic predictions of a banking crisis, or deep recession. Most believe the Kremlin will be able to contain the fallout.

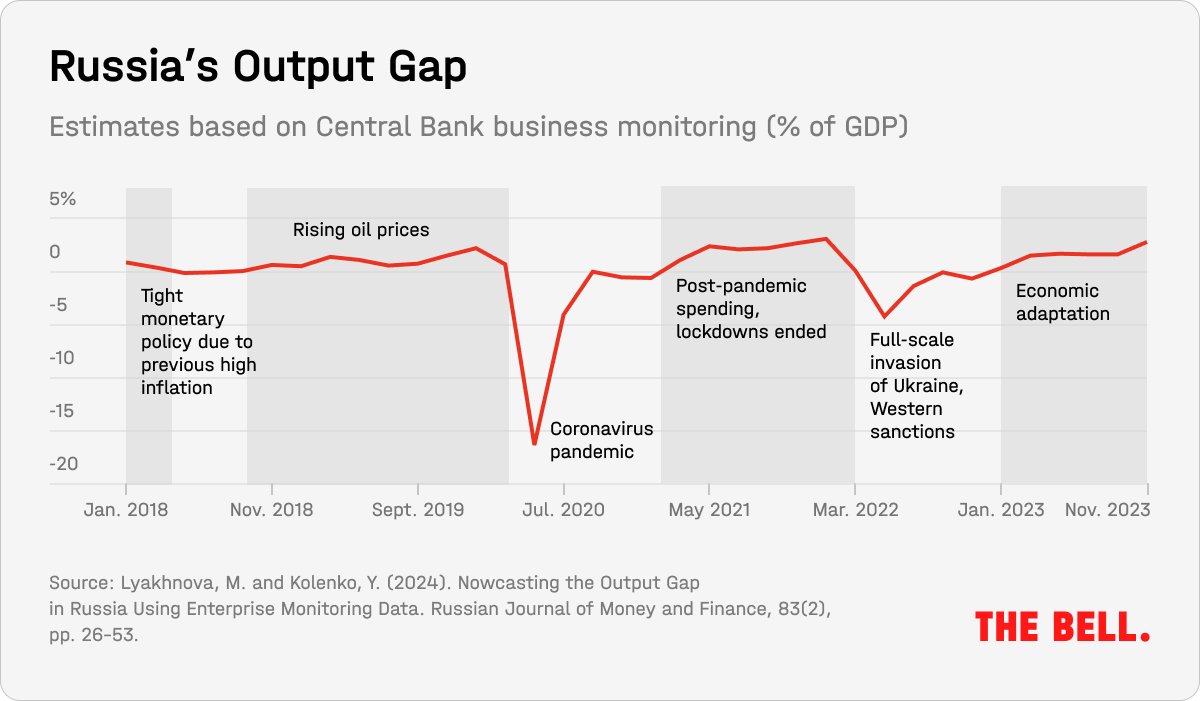

It’s true that a positive output gap (when actual output is more than full-capacity output) can end up in a recession. And this scenario has been widely discussed on influential economy-focused Telegram channels like “Hard Figures” and “MMI.”

Others believe overheating will simply fade away. “Overheating often cools by itself. There is a school of economic thought which says that if you treat a cold yourself it will go away in a week, and if you don’t it will last for seven days,” said the chief economist. Analysts from Moscow’s Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting, an independent research organization, agree there is no recession on the horizon.

To prevent the public from noticing an end to overheating, Russia will need to adopt specific fiscal and monetary policies, according to the chief economist. But the authorities have only limited options. Russia already has a tight monetary policy, and a tight fiscal policy is written into the 2025 budget. Moreover, companies do not have infinite resources to keep raising salaries – and consumers cannot endlessly increase consumption.

Economist Kiselev believes that an end to overheating could result in a possible major correction to prices, or the exchange rate, but there will be no major banking crisis of the type some were predicting following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Why the world should care

While there have been some dire forecasts, most economists now seem to think Russia’s economic authorities will be able to manage whatever comes after overheating. This will come at a cost, however. “The state will neutralize the risk of a financial crisis but, in the future, will have to capitalize loss-making companies and banks,” said Kiselev. “At the end of the day, all that financing will be at the expense of taxpayers and investors.”

Persistent inflation makes interest rate rise all-but inevitable

Russia’s rapid rise in inflation shows no sign of slowing. Between June 18 and June 24, weekly inflation accelerated from 0.17% to 0.22%, according to the Economic Development Ministry. Annual inflation went up to 8.61%.

- Prices are increasing significantly faster than seasonal norms, and this is being driven by underlying components rather than volatile. If we extrapolate the figures for the first 24 days of June we get inflation of 0.73% month on month, according to economist Dmitry Polevoy.

- And inflation shows no signs of cooling – instead, there are a whole host of inflationary factors. Russia is planning to increase communal service tariffs in early July, which will further fuel price rises. In addition, we are also seeing increased demand at the start of the summer holiday season, wage rises, and growing consumer lending. Inflationary expectations are also up.

- The Central Bank’s next meeting to discuss interest rates is scheduled for July 24. And, at least at the moment, each new piece of economic data strengthens the consensus among analysts that rates will rise. A summary of the previous interest rate discussion published last week showed board members opting to wait for further information, and if the inflation persists, to rise the rate sharply, from the current 16% as high as 17-18%.

Why the world should care

The state itself is the main driver of high inflation as the Kremlin ups spending amid the war in Ukraine. And it’s clear that interest rates (even at their current levels) are not doing much to suppress demand. If the current dynamic continues, the Central Bank does not face a choice about whether to raise rates – merely a choice about how high they should go.

Figures of the week

The growth of the mortgage portfolio held by Russian banks increased from 1.4% to 1.7% in April, according to the Central Bank. This may be due to borrowers rushing to secure loans before the planned end of a program of state-subsidized mortgages on July 1.

The Central Bank will make 8.4 billion rubles worth of “irregular” foreign currency sales a day in the second half of this year, compared with 11.8 billion rubles worth in the first six months. This will reduce support for the ruble, which is strengthening against the dollar.

Russia recorded a 5.3% year-on-year increase in industrial output last month. This is slightly above the average figure from January through May (5.2%). In May, year-on-year manufacturing output (particularly in military-related sectors) rose to 9.1% (compared to 8.3% in April). The average from January through May was 8.8%.