This exposé of Moscow’s funeral business is a snapshot of modern Russia

Hello! This week our main story is a summary of Ivan Golunov’s powerful investigation into Moscow’s funeral business that takes in everything from venal intelligence officers to Lamborghinis, nightclubs and a cemetery shoot-out. We also analyse the blame game among officials as the Russian economy slides towards recession, and lay out what we know about the fire that struck a top-secret nuclear submarine operating in the Arctic.

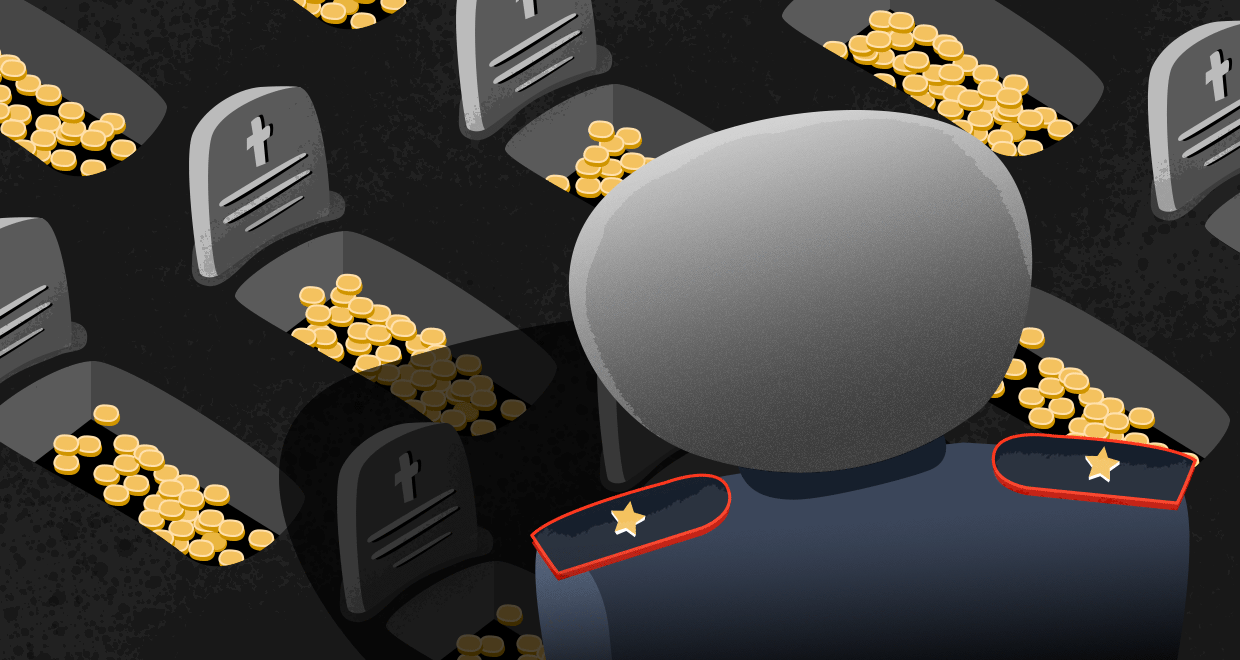

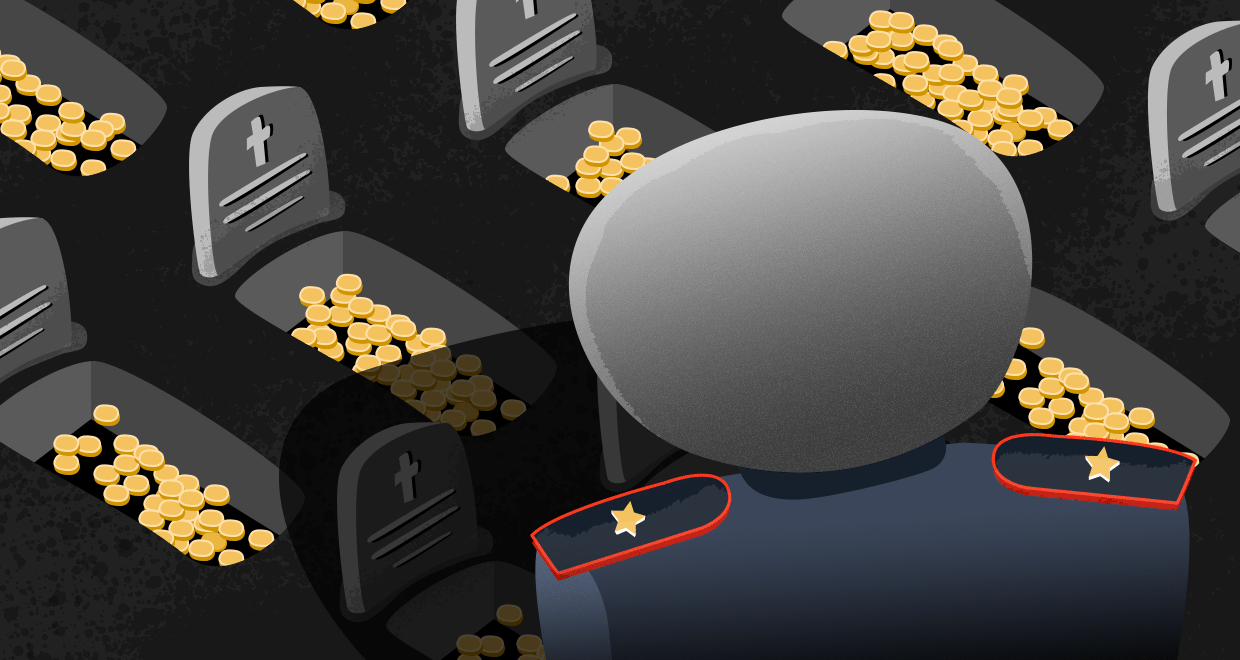

This exposé of Moscow’s funeral business is a snapshot of modern Russia

Journalist Ivan Golunov said last month in court that his yet-to-be published investigation about Moscow’s funeral business may have been the reason he was arrested on fabricated drug charges. Since then, seven Russian publications, including The Bell, have been helping him finish the investigation, which was published this week. The article is extremely complex, but paints a compelling picture of today’s Russia: from pitched battles in cemeteries to the security services, pyramid schemes and an orange Lamborghini worth over $300,000.

- While Russian law states that every citizen must be provided with a free burial, in reality, this is impossible in Moscow. A space in a cemetery far from the city costs 1 million rubles ($16,000), while a plot in a prestigious cemetery near the center can cost up to 4 million roubles ($70,000). It is a cynical business: to get commissions from grieving relatives, undertakers use a network of compromised doctors and police officers. But it is also lucrative: Moscow’s funeral market is estimated to be worth 13 billion roubles ($200 million) annually. The state company that owns Moscow’s cemeteries is called Ritual.

- The funeral business has always been highly criminalized. Since the early 2010s, the most prestigious Moscow cemeteries have been run by former officials from Moscow region. In 2016, one of these ex-officials hired thugs to pressure workers from Tajikistan employed in one of the cemeteries and a huge brawl broke out, guns were pulled and three people were killed.

- After this scandal, Artyom Yekimov, a former police officer, was put in charge of Ritual in the hope he would restore order. Day-to-day management was handled by Yekimov’s deputy, Valerian Mazaraki, a businessman with a dubious reputation. In the early 2000s, Mazaraki owned a vodka factory jointly with his brother, Lev, in Stavropol region in southern Russia. When the authorities tried to shut down the factory for using illegal alcohol, Mazaraki tried to set-up a lottery scheme, but that too was shut down for the illegal use of a photograph of Dmitry Medvedev. In the early 2010s, the Mazaraki brothers worked as top managers in banks known for money laundering. Then, along with Mazaraki, at least 12 people from Stavropol — including a local singer and a former cruise ship waiter — were given managerial positions at Ritual.

- However, it’s likely that neither the former Moscow region officials, nor the appointees from Stavropol, are the real beneficiaries of Ritual. Marat Medoev, the man behind the appointment of Yekimov, is an assistant to Aleksei Dorofeev, the Moscow head of the FSB, Russia’s domestic security service. Meduza’s sources referred to Dorofeev as a “demigod”, explaining that even some senior figures at the FSB can’t get an appointment with him. Dorofeev, Medoev, and Mazaraki own houses next to each other in the same luxury development outside Moscow.

- Russia wouldn’t be Russia if this alliance of security service officers and questionable businessmen didn’t make extravgant purchases. And, sure enough, Lev Mazaraki’s wife owns one of the most expensive cars in Moscow, an orange Lamborghini Aventador LP that cost no less than $300,000. Their son was the owner of several expensive night clubs in Moscow favored by playboys with rich parents.

Why the world should care

Most journalism investigations in Russia do not result in any changes, but this is different. The fabricated case against Golunov was such a big scandal that it will lead to a settling of accounts within the political elite, including resignations and maybe even criminal charges. But the corrupt system, which is controlled by high ranking security officials, will, of course, not change.

Officials are scrabbling for a way of staving off economic recession

The liberal economists in government have a problem: the Russian economy is not just stagnating, but showing signs of recession. The only way to restore growth without serious structural reform is for the government to invest tens of billions of dollars. While the state doesn’t have a problem with access to funds, an influx of cheap money could drive up inflation.

- Signs of a recession appeared one after another this week. First, it emerged that railroad cargo volumes fell 5.4 percent in June, which, for the Russian market, is almost as good an indicator of recession as the inverted yield curve is for economic fortunes in the United States (needless to say, railroad cargo volumes fell badly ahead of the economic crises of 2008-2009 and 2013-2016). Second, we learned that the PMI index of business activity fell below 50 points in June for the first time since 2016. Add to this that Russian GDP grew only 0.2 percent in May, and by 0.8 percent in the first half of 2019, and the picture is not a pretty one. This level of economic growth is not enough to meet the official forecast of 1.3 percent growth this year, let alone the 3 percent annual growth President Vladimir Putin is demanding for his fourth term.

- The main victim of a recession could be Putin’s favorite, Minister of Economic Development Maksim Oreshkin (GDP growth is his responsibility). Oreshkin is in a difficult position. As a former investment banker, he understands that growth is impossible without reducing pressure on private businesses and judicial reform — but he doesn’t have the power to make such things happen. Oreshkin can only try to blame others: last week, he said twice that the Russian economy’s number one problem is a credit bubble that the Central Bank isn’t tackling.

- Elvira Nabiullina, the head of the Central Bank, responded to Oreshkin in an interview with Reuters. Her main point was that stagnation is being caused not by sanctions, which officials like to blame, but by domestic problems: business is depressed, real incomes are not growing, and major reforms are off the agenda. She added that attempts to stimulate growth with cheap state money will destroy macroeconomic stability, and significant interventions by the Central Bank will lead to an increase in inflation and a bubble in financial markets.

The day after her interview, Nabiullina admitted her tough talk will not lead to change. “We have been saying the same words for many years. At first, they seemed correct, then commonplace, then like the empty words of officials — but now they sound like a cries of despair,” she said (Rus) at a banking conference. This is an admission that the Russian economy is at a dead end. While reform is needed for growth, there is no political will for difficult decisions. Ironically, the regime needs growth to survive: Putin’s approval ratings are falling alongside real incomes.

Why the world should care

Government investment remains the only way of creating growth. But despite Nabiullina’s warnings over this path, it appears almost inevitable — and that means that the risk of inflation will increase. The Russian Central Bank may be forced into raising rates.

A fatal nuclear submarine accident in the Arctic remains shrouded in secrecy

Fourteen sailors died as a result of an onboard fire this week on a nuclear submarine that is part of the navy’s Northern Fleet. While we know the vessel managed to return to port, the public was given almost no details about the accident or, most importantly of all, whether there was any serious threat to the stability of the nuclear reactor.

- For Russians, a submarine accident is a particularly emotive event because of memories of the Kursk submarine disaster 19 years ago that defined the beginning of Putin’s presidency. Aside from the horrific death toll, the accident is remembered for the lies told by the military, who revealed the catastrophe one and a half days after it occurred, refused foreign aid and concealed information from relatives of the dead.

- Secrecy was also a hallmark of the latest accident. The fire was only announced a day after it happened, and there still has been no official confirmation of the vessel on which it occurred. On the one hand, this isn’t surprising: no one doubts the fire took place on board the Losharik, a top-secret vessel capable of diving to depths of up to 6,000 meters (the U.S. considers it to be a sabotage submarine, which can cut deep water communication cables). On the other hand, just like with the Kursk, it wouldn’t be a bad thing for society to know the circumstances surrounding an accident on a nuclear-powered submarine. Officially, the Ministry of Defense has given the cause of the fire, but they managed to do this without revealing anything of note.

- No one doubts that the military has to keep secrets, but in the 21st century there is a high risk of being found out anyway — and looking a fool. An excellent example of this is the sole existing photograph of the Losharik, which all Russian and international media used in their reporting of the incident. In 2015, the top-secret submarine accidently appeared in a photo published by the Russian version of car magazine Top Gear, which had organized a photo shoot for a new Mercedes on the edge of the Barents Sea.

Why the world should care

In 1986, the Soviet government revealed a nuclear accident had taken place at Chernobyl two days later; in 2000 the explosion on the Kursk was announced one and a half days after it took place; and in 2019, the Losharik’s fire was announced a day after it happened. On the one hand, you can see some progress. But, on the other, just like in 1986, this week the world looked to foreign radiation detection equipment to gauge the level of danger.