Ukraine’s counteroffensive and economic scenarios for Russia

Hello! This is Alexandra Prokopenko with your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. This week we focus on Ukraine’s counteroffensive and what it could mean for the Russian economy. We also notica that Russian state spending is gradually slowing down.

What could be the economic fallout of Ukraine’s counteroffensive for Russia?

The evidence suggests that Ukraine’s counteroffensive, expected since the start of 2023, finally got underway this week. In the past 15 months of fighting, Ukraine’s allies have steadily switched from “don’t allow Ukraine to lose” to “help Ukraine win.” It’s precisely this conceptual switch that will define the post-war landscape. During this time, Russia has mobilized, dug in and built large defensive lines. The situation is changing fast, and it is very difficult to predict the outcome of the Ukrainian counteroffensive and its consequences for Russia. But that does not mean we cannot review some possible scenarios.

What’s going on?

The start of the long-awaited counteroffensive does not currently seem to involve a concentrated strike in any one direction. Instead, it has brought a series of attacks testing Russia’s defenses. The first of these started on June 4 in the Vuhledar area and, since then, Ukrainian forces have launched daily attacks on different parts of the line in Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk Regions. At the same time, Ukraine continues to shell targets in Russia’s Belgorod Region. Russian military bloggers expect a major assault towards Orikhiv in Zaporizhzhia. A breakthrough in that area would cut Russia’s forces in southern Ukraine in two, severing the land corridor between Russia and annexed Crimea.

Amid the fog of war, we know little about the actual fighting. But we have already seen the first true catastrophe of this campaign. On June 6, in a part of Kherson Region occupied by Russia, the Kakhovka dam was destroyed. Water poured downstream along the Dnieper, flooding thousands of homes and killing some people. Russia and Ukraine are blaming each other for the destruction of the dam. A further possibility is that the dam simply collapsed as a result of earlier damage and Russian negligence. On Thursday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyi visited the flooded areas. Russian President Vladimir Putin has no plans to do the same, Kremlin press secretary Dmitry Peskov said.

The destruction of the dam threatens both sides with serious economic consequences (the flood zone covers territory currently held by both Moscow and Kyiv). The immediate problem is how to accommodate refugees and pump water from the inundated areas. The dam’s collapse had an immediate impact on the grain market: in Chicago, grain futures were up, Bloomberg reported. According to Andrei Sizov, director of the SovEkon analytical center, traders view it as a sharp escalation with serious consequences.

One of the main long-term problems, according to UN experts, will be maintaining water supplies to the population of southern Ukraine. When intact, the Kakhovka reservoir provided water for about 700,000 people in a region that included Crimea. Until 2014, Ukraine supplied Crimea with water through the North Crimean canal, which connects to the Dnieper. After Russia annexed Crimea, the canal was blocked. The Russian authorities allocated billions of rubles for the construction of new waterways and wells. However, the problem was only resolved after the 2022 occupation of the part of Kherson Region through which the canal flows. Following the destruction of the dam, the canal is likely to run short of water.

From a strategic point of view, the collapse of the dam is unlikely to affect any Ukrainian assault, according to military expert Michael Kofman. “A Ukrainian operation to cross the river below the dam, in the southern part of Kherson, was always a risky, and therefore unlikely proposition,” he wrote on Twitter. The destruction of the dam will neither lead to a significant weakening of the Russian line, nor facilitate its defense. If Ukraine’s plan is to break through the Russian line in Zaporizhzhia and cut off the land corridor to Crimea, the flooding is unlikely to hamper that operation, Kofman added.

The outcome of the counteroffensive is difficult to predict. However, the likely consequences for Russia’s economy will fall somewhere between two extreme circumstances.

In case of Ukrainian success

A clear victory for the Ukrainian military would include the recapture of a significant part of the occupied territories in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. In that event, as many in Kyiv and the west have suggested, Putin would likely face a major political crisis. However, it's difficult to say how serious this would be, and what form it might take. If it does happen, we can expect further repression, more mobilization and a full shift to a war economy.

The defense sector is now one of the main drivers of the Russian economy. Defense and security is the single largest area of spending in 2023 and, by June 1, almost 60% of those funds had already been allocated. Production and supply of weapons has increased seven-fold, Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov said last month. There is also a drive to repair and supply tanks and armored vehicles. According to Manturov, deliveries of repaired vehicles in the first quarter of this year were equivalent to the total deliveries throughout 2022. Pavel Luzin, a visiting fellow at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, estimates that at its pre-war peak Russia was building or upgrading 150-180 tanks a year. It has been losing roughly that number every month in Ukraine.

It’s important to remember that Russia’s defense needs are being met by defense industry enterprises and repackaged civilian factories that chose (but are not ordered) to pivot toward military production. A full-scale mobilization would mean many more civilian industries will move to military production, with a knock-on effect for civilian goods. At the same time, the government would reduce civilian expenditure in favor of the military (which has not happened so far). The rhetoric of a showdown with NATO and calls to fight a “holy war” would likely form the crux of Putin’s campaign during the 2024 presidential election.

In case of a Ukrainian failure

The other extreme scenario is a pessimistic one for Ukraine. If the summer offensive does not yield any results, the Russian Armed Forces could launch its own offensive and seize more territory. However, this outcome seems unlikely — most Western analysts believe Russia lacks the military strength for a successful assault. It’s also improbable because it would likely trigger even more Western military and financial aid for Ukraine.

For Russia’s economy, this outcome would mean more of the same, at least in the short term. Military expenditure would remain at least at 2023 levels (the army needs to replenish its arsenals), and would probably increase. There would also be no reduction in spending and there could be significant pre-election handouts.

In Europe and the U.S., military expenditure would increase to boost production. Millions of Ukrainian refugees in Europe would remain there for at least another year, boosting the labor market in Poland and other Central European countries. A new “Marshall Plan” for Ukraine would likely remain under discussion.

Why the world should care

Politicians and commentators in Europe, particularly in Germany, hope the Ukrainian offensive will lead to a truce. U.S., British and Central European analysts believe that it will take at least one more significant defeat to bring Russia to the negotiating table. However, regardless of the outcome of the summer campaign, it remains important for Ukraine's allies to give guarantees that they will continue with military and financial aid. Another, perhaps more long-term, task is to provide security guarantees that would prevent any future conflict. Ukraine needs a “porcupine strategy” that ensures any invader would face such huge losses that a future attack would not be worthwhile.

The rate of state spending is gradually slowing

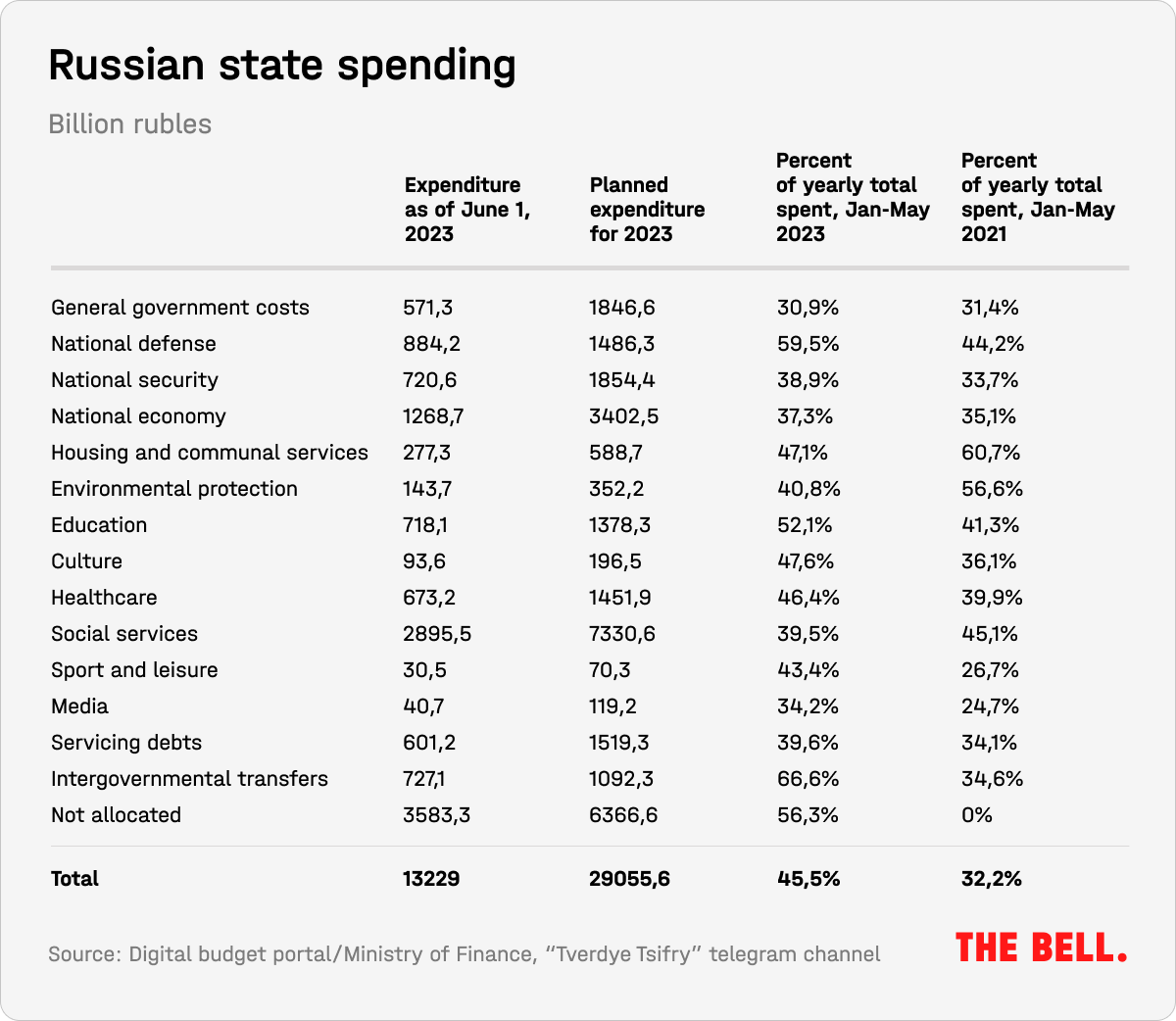

Spending is slowing, but remains high. The Finance Ministry has said that, from January through May 2023, spending was up 27% on the equivalent period last year (reaching 13.2 trillion rubles). While monthly spending dynamics are approaching normal levels, they are still a long way from seasonal norms. The accumulated year-end deficit remains about 3.4 trillion rubles — above the 2.9 trillion rubles allowable under budget rules.

Total revenue in the first five months of the year was 9.8 trillion rubles (-18% year-on-year). Oil and gas revenues of 2.8 trillion showed a predictable decline from last year’s record (-36% year-on-year in May). Non-oil and gas revenue for these five months amounted to 6.97 trillion rubles (+9% year-on-year).

Why the world should care

The public spending trend is still not clear at this point in time. In the past, as a rule, the government has ramped up spending at the end of the year, allocating up to one third of the budget in the last two months. It’s already clear that this year’s budget deficit will go beyond the level prescribed by Russia’s own rules — the question is by how much. The bad news is that the government still has resources to cover even a very large budget deficit.

Russians stop saving, start spending

In May, banks issued a record 1.41 trillion rubles of credit, according to Frank RG’s express monitoring. The month, not usually a high spot for loans, showed unexpected increases even compared with April. The figures were higher not only than December 2022 (1.38 trillion rubles) but also December 2021 (1.39 trillion). According to Frank RG, the biggest increases were for non-targeted loans and car finance, which were up 11.4% and 8% respectively last month. “We are seeing a change in the model of financial behavior… more and more people are taking out loans while keeping a savings account,” said Anton Anishchenko, a board member at Pochta Bank.

Riyadh against hidden OPEC+ subsidies

Saudi Arabia appears to be disappointed with Russia’s failure to carry out its promised oil production cuts. In 2016, when Russia joined the OPEC+ oil cartel, it was assumed that Moscow and Riyadh would coordinate closely. The partnership lived through its first breakdown in 2020, when both sides waged a spectacular price war, quickly forced to an end by the COVID-19 pandemic. This time, Russia has, in fact, refused to fulfill its own obligation to cut oil output. And Saudi Arabia has, for the first time, publicly voiced what its diplomats have been whispering to journalists for the last two months: OPEC+ and Riyadh aren’t sure that Russia is abiding by its self-imposed production quotas.

Russia has classified its oil production statistics, so it is difficult to check if Moscow is keeping its promises. Furthermore, it is reasonable to suspect that, right now, Russia is trying to export as much oil as possible to fill the growing gap in its budget.

And it turns out that the UAE is also not going to cut its crude output. Moreover, they have managed to negotiate an increase of their quota with the Saudis. It seems that both Russia and the UAE can afford to sell oil at lower prices and, due to political considerations, there is little Saudi Arabia can do about it. Riyadh doesn’t want a feud with Moscow to hurt its normalization of relations with Iran, the fragile peace in Syria and its flourishing international trade. So, it turns out that the biggest oil producer in the world is waging a one-man fight to boost the energy prices — involuntarily subsidizing Russia and the other OPEC+ members.

Key figures

The Finance Ministry in May continued to sell gold and Chinese yuan from the National Wealth Fund (NWF) to cover the budget deficit. The ministry sold 2.6 billion yuan and 3.85 tons of gold for a total of 48.96 billion rubles. Over the month, the NWF was reduced by 1%. On June 1, it held 12.35 trillion rubles, equivalent to 8.2% of Russia’s predicted 2023 GDP. The fund’s liquid assets dropped to 6.64 trillion rubles.

This month, the Finance Ministry will sell 3.6 billion rubles worth of yuan each day, raising almost 75 billion rubles monthly. Additional oil and gas revenues in June will raise 44 billion rubles. Income in May 2023 turned out to be 30.6 billion rubles lower than anticipated.

In the week commencing June 5, inflation accelerated to 0.21% from 0.08%. Historical norms for this period range from 0-0.2%, so the current increase is big.

Inflation accelerated to 2.5% y/y or 0.31% m/m in May, exceeding the analysts' forecasts. Services rose at a faster rate in May: +11.0% y/y and +1.13% m/m.

The Bank of Russia kept its key rate at 7.5%, but the signal tone became more hawkish.

What to watch this week

Review of financial market risks (Central Bank, June 13)

Weekly inflation from 6 to 13th of June (Rossat, June 15)

Russia’s GDP 1Q 2023 (first assessment, Rossat, June 15)

Vladimir Putin will speak at SPIEF’23 (June 16)

Further reading

Alexei Gusev explains Why Support for Putin’s War Is Rife in Russia’s Worst-Hit Regions

Russia’s Lonely Fleets – Pavel Luzin reflects on what NATO expansion means for the Russian Navy

Tech Sanctions Against Russia – Alyona Epifanova on turning the West’s assumptions into lessons

The author of this newsletter is one of Russia’s leading writers on this topic: independent economic analyst Alexandra Prokopenko. Alexandra worked as an advisor at Russia’s Central Bank and Moscow’s Higher School of Economics from 2017 to 2022 — and before that she was an economic journalist for Vedomosti, then Russia’s leading business newspaper. Today, Alexandra works as a researcher at Center for East and European Studies (ZOiS) in Berlin a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a visiting fellow a the Center for Order and Governance in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia at the German Council on Foreign Relations. She holds an MA in Sociology from the University of Manchester.