Why does Russia have a yuan shortage?

Hello! Welcome to your weekly guide to the Russian economy — written by Denis Kasyanchuk and Alexander Kolyandr and brought to you by The Bell. This week, our top story is a deep-dive analysis of Russia’s yuan liquidity crisis. We also look at the escalating conflict over online retailer Wildberries with Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov recently declaring a blood feud with his corporate opponents.

Demand for Chinese currency in Russia causing cracks in the system

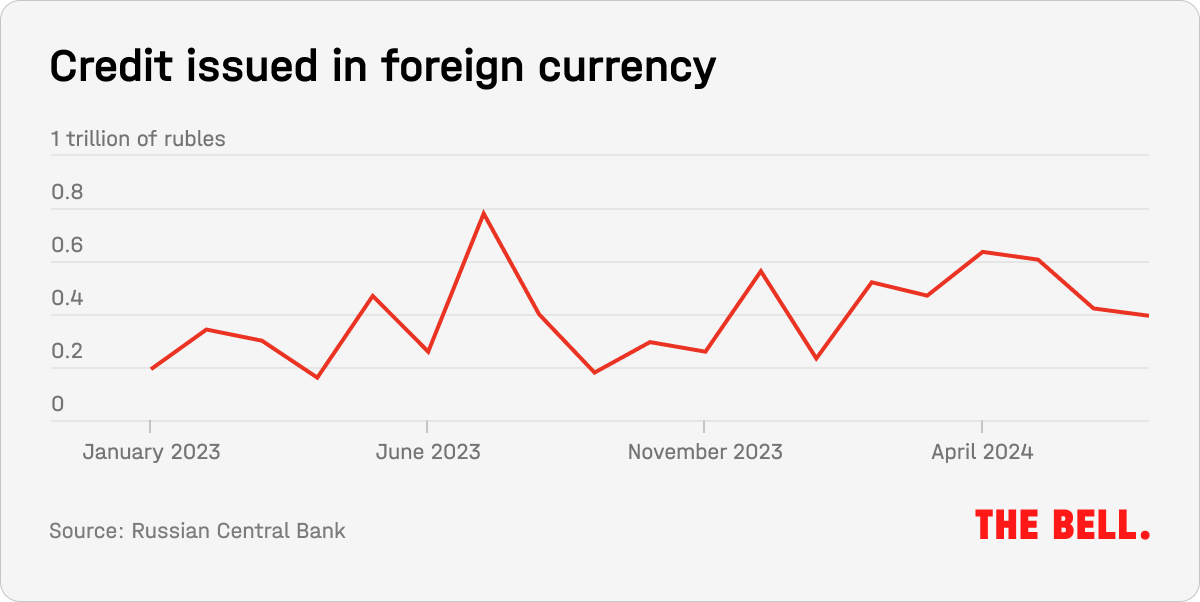

With interest rates in Russia at almost 20% – making borrowing in rubles almost unsustainable – yuan-denominated loans have been a lifeline for some Russian companies. But there isn’t enough Chinese currency to go around. In recent months, the market suffered a yuan liquidity crisis. We decided to take a close look at the yuan shortage, and what it says about broader problems for the Russian currency markets.

What’s going on?

The yuan has become the main foreign currency in Russia for three reasons: Western sanctions, a shift away from what the Kremlin sees as “toxic” U.S. dollars and euros, and increased trade with Asian countries. Before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there was almost no demand for yuan, but, by May 2024, it was being used for 54% of all transactions on the Moscow Exchange. After Western sanctions were imposed on the exchange this year, the figure jumped to 99.8% (in 2022, more than 80% of trades on the exchange took place in U.S. dollars, and the rest were in euros).

With Russia’s interest rates likely to keep rising, there is unexpected demand for loans in yuan among Russian companies who want lower interest rates. In 2024, the average rate for a business loan in rubles (excluding SMEs) was 17.17% for loans of less than a year and 14.74% for longer-term loans. Loans in yuan have much lower rates — 7.11% for short-term and 8% for longer-term loans (79% of loans are over one year or less).

It’s most often businesses engaged in foreign trade that take loans in yuan. “With expenses in yuan, it’s easier for businesses to take out loans in this currency than seek credit in rubles, convert them to yuan, spend them, generate revenue in yuan, convert them back to rubles and repay. For exactly the same reason, various exporters liked to borrow in dollars and euros,” said Russian banker Sergei Skatov.

However, in recent months, Russia faced a yuan liquidity crisis (in other words, demand for the Chinese currency outstripped supply). Banks were unable to lend in foreign currency because they had nothing with which to close their open currency positions, the head of state-owned Sberbank, German Gref, said at the Eastern Economic Forum in early September. In recent months these liquidity problems have led to a slowdown in lending.

The peak of the yuan liquidity crisis came last month. The rate on a one-day repo in yuan (a currency sale with a buy-back obligation), which reflects the costs of attracting and placing liquidity, cleared 212% after shooting up almost four-fold in a single day. The Moscow Exchange had never previously seen such figures.

Who’s to blame?

The liquidity problems are more complex than they may seem at first glance. From the Central Bank’s point of view, there isn’t any actual problem with yuan liquidity, only problems with closed currency positions. Simply put, they believe banks are not lending yuan to clients because they need the money themselves to “balance” the volume of claims (what the bank is owed) and liabilities (what the bank owes) in currency on their balance sheets.

In order to do this, banks received liquidity from the Central Bank using currency swap operations: a transaction to sell yuan for rubles with their subsequent purchase for a period of one day. This is an alternative to currency repo. The regulator launched this instrument in early 2023 to help ease exchange rate volatility on the money markets.

The Central Bank was not happy with the yuan shortage. At first, the regulator tried to accommodate banks by raising the total swap limit from 10 billion yuan ($1.42 billion) to 30 billion yuan. Then it hiked swap rates, making it more expensive to raise money.

At a September press conference, Central Bank deputy head Alexei Zabotkin explained the logic behind that decision: banks should not be using swaps to fix their own funding problems under the guise of grappling with liquidity issues. In fact, he told banks to go and find the currency they needed for themselves. Usually, banks raise money via deposits. But for the yuan to remain in Russia’s domestic financial system, somebody needs to be ready to accumulate it – and, at present, there is no demand for yuan savings in Russia.

“Up until now the problem with Russia’s yuan market has been that it is segmented, or not properly formed, neither in terms of pricing, nor in terms of balancing supply and demand for credit and deposit,” said economist Yegor Susin.

Other factors

Yuan liquidity significantly worsened ahead of Sep. 20 when state-owned oil giant Rosneft first issued 15 billion yuan’s worth of bonds, according to Russian lender Alfa-Bank. Ahead of this date, banks tried to accumulate the yuan that they would need when presenting the bonds for redemption. After the payment was made, the rate for raising yuan on the Moscow Exchange dropped from 17.76% to 13.54%.

The continuing problems making payments through Chinese banks that began after U.S. threats to impose secondary sanctions on companies aiding Russia is also complicating matters. Russian exporters face delays in getting revenue, and the only way to fulfill their obligations is to borrow yuan from Russian banks, according to analysts.

A further reason for the problems with yuan liquidity are U.S. sanctions imposed on Russia’s National Clearing Center (NCC) in July, a banker involved in the currency markets told The Bell. In his view, the sanctions open up an opportunity for speculative earnings on the difference in rates, which, in turn, requires a lot of yuan. As a result of the sanctions, Chinese banks stopped servicing payments for the Moscow Exchange and NCC, so the Central Bank and exporters lost the ability to withdraw currency and the yuan exchange rate fell by 10% relative to the international reference rate. It then became possible to withdraw yuan from Russian banks and profit from the difference in rates – but there wasn’t enough cash. While withdrawing yuan from the Moscow Exchange is difficult, it remains possible.

What happens next?

“I wouldn’t expect the situation to get any better in the immediate future,” Sberbank executive Taras Skvortsov said at the Eastern Economic Forum last month. A few days later, Skvortsov even admitted that trade in the yuan could be halted on the Moscow Exchange. If that does happen, it will most likely take place after the Oct. 12 expiration date imposed by the U.S. for companies to curtail operations with the Moscow Exchange, the NCC and the National Settlement Depository – or be hit with sanctions.

A halt in yuan trading would drive up costs for all importers and exporters, a source connected with the Russian currency market told The Bell. At the same time, there is no talk of stopping settlements entirely: while Europe continues to purchase Russian exports (notably gas) solutions will be found, he said.

Why the world should care

While the yuan has replaced the U.S. dollar as Russia’s preferred currency for international settlements, it is far from ready to actually fulfill this role. Disbalances are inevitable. But problems risk impacting not only on business and currency traders. Amid the yuan liquidity crisis, the ruble has fallen about 15% since the end of August. For Russian consumers, this means exports from China are becoming more expensive.

Kadyrov declares blood feud with corporate foes

Two weeks after a fatal shoot-out at the Moscow office of Wildberries, a battle for control over the so-called Russian Amazon shows no sign of ending. The stand-off between the two most powerful men in the rival factions, Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov and billionaire Suleiman Kerimov, appears to be escalating. Kadyrov claimed Wednesday that Kerimov and his partners had ordered his assassination and, in response, declared a blood feud. The remarks were widely covered by state media.

- As well as Kerimov, Kadyrov also declared a blood feud against parliamentary deputies Bekkhan Barakhoyev and Rizvan Kurbanov. Kerimov, one of the 10 wealthiest people in Russia, is believed to be behind Russia’s biggest outdoor advertising company, Russ, which is currently merging with Wildberries. Barakhoyev is a co-owner of Russ and Kurbanov is a Duma deputy assumed to be Kerimov’s man. The merger with Russ was negotiated by Wildberries founder Tatyana Bakalchuk against the wishes of her husband, Vladislav (who risks losing his stake in the company). The couple are apparently divorcing. To halt the deal, Vladislav turned to Kadyrov for assistance. You can read the full background to the story here.

- In his announcement of the blood feud, Kadyrov claimed that Kerimov and the two deputies were responsible for the Wildberries shoot-out and, moreover, wanted him dead. “There are witnesses, there are people with whom they placed the order, who they asked how much they could do the job for. If they cannot prove otherwise, I officially declare a blood feud on Barakhoyev, Kerimov and Kurbanov,” Kadyrov said. State-owned news agency TASS happily relayed Kadyrov’s speech to the world.

- A blood feud is a patriarchal custom that involves the murder of any member of a rival’s family. It still sometimes happens in Russia’s North Caucasus, even though it is, of course, illegal. The European Refugee Agency defines a blood feud as a conflict “between non-state parties, such as ethnic groups, in places where state authority and the rule of law are weak or absent.”

- Two security guards were killed in last month’s shoot-out at Wildberries’ Moscow headquarters. Both men were from Ingushetia, a region neighboring Chechnya. When their bodies were returned to their homeland, there were large demonstrations at which locals protested against, among other things, Kadyrov’s regional dominance. There is a history of tension between Ingushetia and Chechnya. In 2018, Kadyrov forced Ingushetia’s government to give Chechnya a chunk of territory and, as recently as two years ago, he threatened to seize more land.

Why the world should care

Aside from the immediate victims of the conflict, Russian President Vladimir Putin himself increasingly appears to be a loser in this corporate dispute that has spiraled out of control. Although the president gave the go-ahead for the Wildberries merger, Kadyrov’s involvement has seen it become something of a clan war. Putin’s legitimacy rests on a general recognition among leading businessmen that he alone is the indisputable arbiter of property rights in Russia. The Wildberries struggle calls that status into question.

Figures of the week

Inflation at the end of September was 0.48% month-on-month – and 8.6% year-on-year, the State Statistics Service announced Friday. This was less than in August (9% year-on-year). Data from the first week of October showed that price growth is slowing – in the week beginning Oct. 1 inflation was 0.14% (down from 0.19% the week before).

It will get significantly more expensive for foreign companies to sell assets in Russia, RBC reported Thursday citing government sources. The required contribution to the federal budget (an “exit tax”) from the sale of foreign businesses will climb to 35% (it’s currently 15%), according to RBC. Deals valued at more than 50 billion rubles will require Putin’s personal approval. It’s true there are not many Western companies still looking to leave Russia. But these tougher restrictions might slow down the departures of, for example, Austria’s Raiffeisen Bank or international foods giant Pepsico.

Russia’s 29 leading exporters last month reduced currency sales by 30% compared with a month earlier. Sales in September were $8.3 billion. This is due to changes in the structure of export settlements, with ruble settlements playing an increasingly important role, according to the Central Bank’s Financial Risk Review. One of the reasons exporters are turning to the ruble are the difficulties receiving payments in foreign currencies. Due to the risk of secondary sanctions, payments are being routinely delayed and sometimes refused, especially when trading with China or Turkey, Bloomberg reported this week.

Further reading

Russia Budgets for its Forever War

Russia’s new budget is a blueprint for war, despite the cost