How does Russia’s drift toward totalitarianism affect the economy?

Hello! This is Alexandra Prokopenko with your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. Our top story is the amendments to a military service law that entails a radical restriction on freedoms inside the country. We also look at why inflation is not falling as quickly as officials claim and the high-ranking security officer who fled Russia.

Military service law is a major curb on freedoms

Putin’s regime last week took a big step towards total control over its citizens. Both houses of Russia’s parliament approved amendments to a law on military service and military registration, formally equating an electronic summons with traditional call-up papers. In addition, they accepted serious restrictions on constitutional rights, including restrictions on foreign travel, in a bid to stop people evading military service. The regime is becoming more and more naked in its aggression against its own citizens. We'll take a look at why this is bad news, not only for ordinary Russians but also for the economy and the authorities.

What’s happening?

In the space of less than a week, both houses of Russia’s parliament rushed to approve a law that gives full legal force to an electronic call-up for military service and creates a digital database of those eligible for military service. On Friday evening, the law was signed by Vladimir Putin. This is directly linked to the Gosuslugi portal – used by millions to handle day-to-day interactions with the government – and will be under the control of military commissariats. By order of the Defense Ministry, the Ministry of Digital Development will create the database and almost every ministry will contribute data: from the Tax Service and the Interior Ministry to employers and educational institutions. People can be added to the register without ever physically attending an enlistment office. For example, in the year when a man turns 17, or after gaining Russian citizenship, he will automatically be added to the service register.

The law comes into force from the moment of its publication. Digital Development Minister Maksut Shadayev was quick to calm the situation, saying that the register would only be working “in full” during the fall conscription period. However, that does nothing to prevent the register working to a limited extent (whatever that means) right now. The new law does not only affect conscripts, but everyone eligible for military service. Now, anyone with “grounds” (such as women who have a military specialty or men over 27 years but who did not complete their military service) can be remotely enrolled. Russia is continuing its latent mobilization, so anybody on the list could be called for military service at any time.

How will Russians be called up?

Alongside the traditional call-up papers, conscripts can also be summoned electronically. Any electronic summons is considered served as soon as it appears in a personal account, regardless of whether or not it has been read. This does not merely mean a message in a Gosuslugi account, it could be any account or “information system” among the many that are being created alongside the new military register. As a result, the now-popular tactic of simply deleting a Gosuslugi account will not save anyone from the draft.

As soon as a summons is delivered, the subject is banned from leaving the country. Anyone who fails to report to an enlistment office without good reason within 20 days of the date of the call-up will be unable to take out a loan, register ownership of property or vehicles, or register as self-employed. Banks will be obliged to check the register before issuing loans.

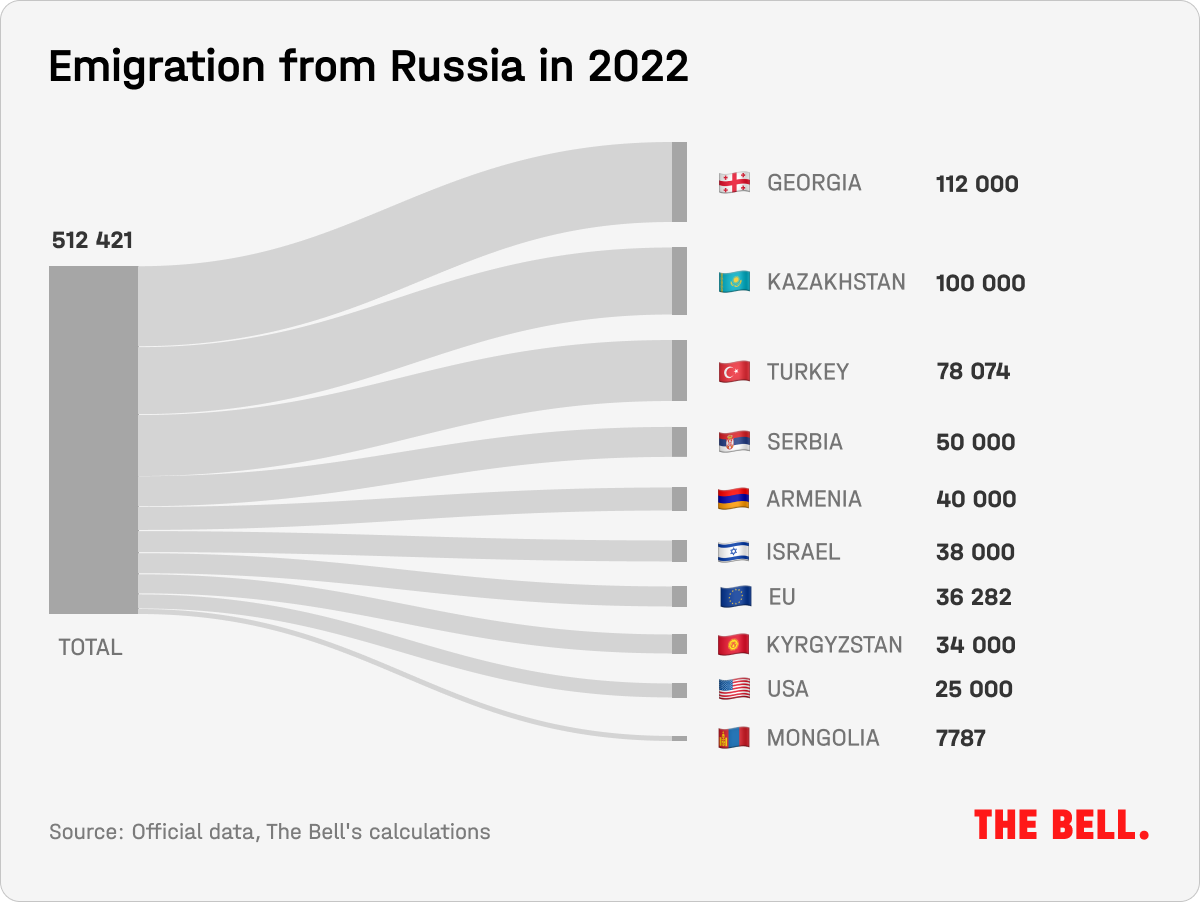

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the country experienced two big waves of emigration. The first came in March 2022 and the second was in September after mobilization was announced. One of the more memorable images of that time showed traffic jams backed up for several kilometers at a checkpoint on the Georgian border. The authorities have not announced an exact figure for those who have left the country permanently. The Bell’s minimum estimate is that more than 500,000 people have gone into exile. Despite assurances from the authorities that few people left, it’s clear this is painful for the Kremlin.

Why is the law needed, and how was it adopted?

The authorities adopted the new legislation in blitzkrieg fashion. On the eve of the draft, Rear Admiral Vladimir Tsimlyansky, head of the main Organizational and Mobilization Directorate of Russia’s Armed Forces, let slip that electronic call-ups would be issued. State media were then banned from reporting this statement, an official told The Bell. This was confirmed by an employee of a state media organization: “the ban came from the Kremlin.” On the same day, the Gosuslugi portal removed the option of deleting an existing account (later it was returned).

Immediately after the bill was adopted, the authorities issued a “manual” (seen by Meduza) to explain to journalists how to report the new law. Apparently it is to do with “eliminating shortcomings in the military registration system.” However, on national television, Duma committee chief Andrei Kartapolov let slip that the law was essential to “deploy mobilization.”

Clearly, the deputies are just a front. However, it is not known who is behind the new law. For the government, which is also responsible for demographics and the labor market, the news came as a surprise, two federal officials told The Bell.

“There were no meetings, there was no consideration of a possible third wave of emigration,” one of them said.

Two sources close to the Kremlin told Meduza that Kremlin officials were unaware of the changes and played no role in drafting the legislation. Meduza’s sources are certain that the amendments came from the Defense Ministry. However, a federal official disputes this, insisting that it would be impossible to push through the bill without the Kremlin: “The military does not carry sufficient weight to push through a law that would have such a powerful impact on society and the economy while the country is in special operation mode,” he said. “Unless there have been some decisive changes in the structure of the regime.”

The economy and the labor market

Apart from an electronic summons, which is almost impossible to evade, the law makes it possible to sign up conscript soldiers for three year-contracts right away (previously, the maximum initial contract was just three months). At the same time, there are almost no limits on the nature of the contract during mobilization. This means that any conscript could theoretically be sent immediately “to the zone of the special military operation.” Thus the military can now ignore Putin's public pledge that conscripts will not be sent to fight. There are plenty of examples of how the military forces conscripts to sign contracts (see here or here). Now, contract military service will become voluntarily-compulsory. In late March a source told Bloomberg that the Russian authorities wanted to avoid a second wave of mobilization, but also planned to recruit 400,000 contract soldiers for the war.

The law should not have a direct negative effect on the economy, but it will likely be destabilizing: increased anxiety among the population and the business community, coupled with rising uncertainty, discourages investment. Moreover, there is a risk of a third wave of emigration. For individuals and businesses, the key issue when planning is the likely duration of the conflict. Alexander Isakov of Bloomberg Economics said: “If the passage of the law is taken as a signal that [the conflict] will go on longer than expected, then we will see lower consumer confidence and a continued high level of savings.”

In 2022, 1.3 million people under the age of 35 left the workforce, according to official figures. Russians aged 25-29 were most likely to leave. Research attributes this to an aging demographic and emigration. The war in Ukraine is not mentioned, but it is a real factor that influences the labor market. The FSB estimates that Russia lost 110,000 people killed or injured in Ukraine, the New York Times writes with reference to leaked U.S. intelligence reports. Reuters, referring to another document from this leak, reported that the U.S. military estimates Russia’s losses from 189,500 to 223,000 men, of which up to 43,000 have been killed. In early April 2023, Mediazona and the BBC Russian Service, along with a team of volunteers, used open data to identify 19,688 Russian soldiers killed since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As the wounded leave the workforce, there is nobody to replace them. There are few men left on the labor market (we wrote about this here) and in several regions women are being hired to fill roles traditionally performed by men.

More bans and restrictions

In parallel with “digital mobilization,” lawmakers have been considering the possibility of imposing a life sentence for treason. Since the start of the year, at least 17 Russian citizens have been arrested for treason (there were 20 such cases in the whole of last year). “This stems from the fact that Putin’s model of government is now in place forever and any betrayal of him – whatever that means in an arbitrary interpretation of their own law – is punishable by eternal imprisonment,” expert Andrei Kolesnikov wrote in a recent analysis.

In addition, it recently emerged that officials and employees of state companies and corporations face restrictions on leaving the country. Recent changes mean that all top officials – from ministers down to heads of department – can only travel abroad with the express permission of Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin.

And that permission is only given when there is a clear operational need, reported The Bell. Some officials have been obliged to hand over their passports. And there were media reports that, over the New Year holidays, both national and regional-level officials were banned from leaving Russia. The Federal Security Service (FSB) maintains a database of officials, governors and other state employees who must obtain special permission in order to leave the country. “An iron curtain for those associated with the state is… in place,” a senior Russian government official said at the time.

Why the world should care

When war broke out in Ukraine, the Kremlin did everything it could to prove that mass emigration from Russia was not something that troubled the authorities. However, the ever-widening restrictions (first security officers, then officials and now conscripts) on leaving the country tell a different story. It appears that the Kremlin cannot rule out a further deterioration in the situation, which might provoke another wave of emigration, but is still unwilling to close the borders. “The situation is something of an emergency, which has left the political regime writhing and convulsing. This could lead to transformations that it never even planned,” said political analyst Ekaterina Shulman.

Don’t be fooled by ‘rapidly falling inflation’ stats

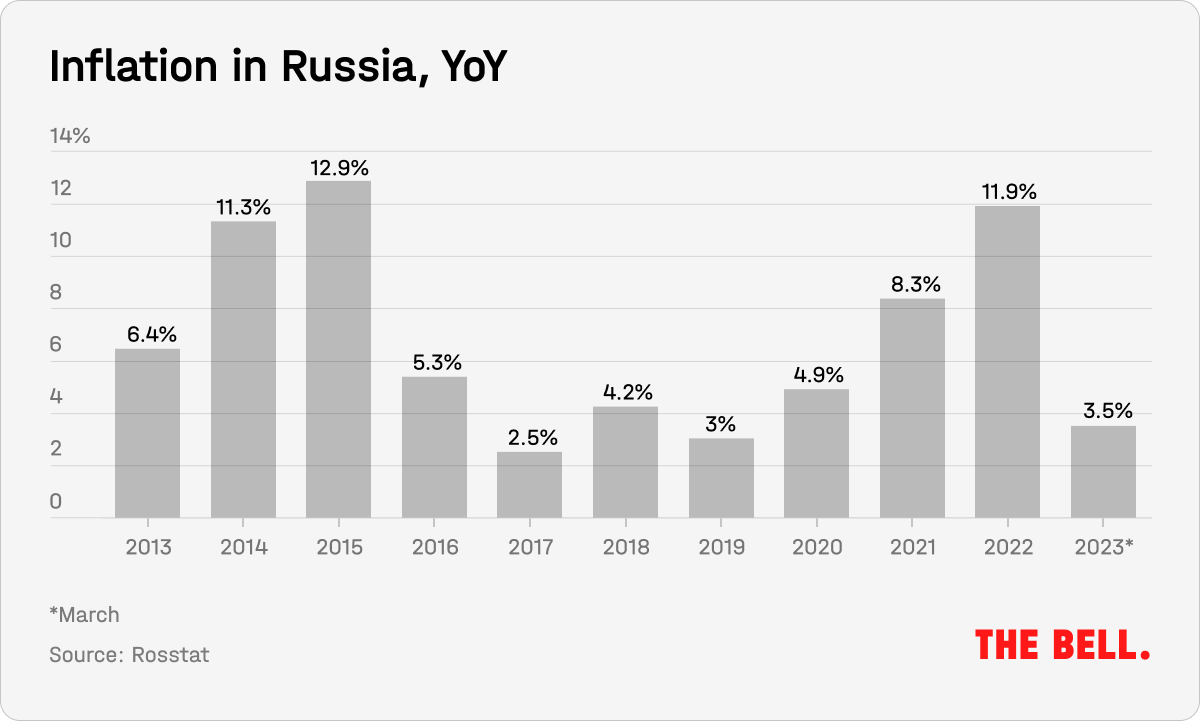

In March 2023, the price growth index slowed to its lowest point since 2020 – 3.5% year on year, or 0.37% in monthly terms, the State Statistics Service reported. However, in annual terms this is a rapid fall — in February, inflation stood at 10.99%.

At a recent meeting on economic issues, Puin was quick to celebrate low prices. However, the announcement of these impressive figures has nothing to do with the strong performance of Russia’s economy and everything to do with the high starting point. Prices in March 2023 are being compared with March 2022, just after the war broke out, when inflation reached 16.7%. Not surprisingly, against such a high baseline, annual inflation in March shows a record low. These figures will continue for the coming months and it is important not to be misled by them. The Central Bank expects inflation at 5-7% over the course of the year.

Security officer who fled Russia tells of Putin’s growing isolation

Gleb Karakulov served for 13 years in the FSO, which is responsible for the president’s personal safety. Karakulov's role involved providing secure communications for the head of state on work trips in Russia and abroad. The interview with him was published last week by Dossier, an investigative center linked to former Russian oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

- Putin does not use the internet or a mobile phone and gets all his information “only from people who are close to him,” according to Karakulov. When preparing a “residence” (like a hotel suite) for a visit from the Russian president, he said, there is a requirement that Russian TV channels must be available.

- According to Karakulov, Putin remains in self-isolation and those who plan to meet him are expected to spend two weeks in quarantine, even if the event is to last less than 20 minutes. “Everyone is at a loss as to why this is still going on,” said the FSO officer. He believes that the president is afraid for his health, although he has no “super critical” problems. In total, since 2009, Putin has canceled just a couple of trips due to illness, according to Karakulov.

- Karakulov also said that on every foreign trip, Putin brings a “talking booth,” a 2.5m high cube with a workspace and a telephone through which you can speak without fear that the conversation will be intercepted by foreign intelligence.

Why the world should care

Karakulov’s account backs up many other reports of Putin’s growing isolation and his self-imposed quarantine. His account of working trips with Putin matches up with what several Kremlin correspondents describe (the author of this text was part of the Kremlin press pool from 2008 to 2017). Karakulov’s statements about Putin’s robust state of health are significant. They contradict allegations that the Russian president is seriously ill.

Key figures

- Trade turnover between Russia and China reached $53.84 billion in Q1 2023, according to China’s General Customs Administration. That’s up 38.7% on the equivalent period in 2022. Exports from China to Russia were up 47.1% and reached $24.07 billion in those three months; imports of goods and services from Russia increased 32.6% to $29.77 billion. In March alone, the volume of trade between the two countries was $20.06 billion.

- The yuan overtook the U.S. dollar in total trading volumes on the Moscow Exchange (39% vs. 34%), reported the Central Bank. The public purchased 121.8 billion rubles’ worth of foreign currency in March, of which 41.9 billion rubles were spent on yuan. After actively acquiring the yuan in March, they then began actively selling it in April. The Central Bank reported the largest sellers increased foreign currency sales to $11.6 billion (+$3.8 billion from February).

- On Friday, the Ministry of economic development released its latest forecast for 2023, Key figures: GDP growth 1.2% (was -0,8% in Sept), inflation 5.3% (5.5%), real wages 5% (2.6%), average Brent price $80.7, average rub/$ rate 76.5.

- From April 4-10, weekly inflation eased from 0.13% to 0.11%, according to the Economic Development Ministry. Annual inflation slowed to 3.15%.

- The current account surplus for March was $5.7 billion, almost unchanged from $5.8 billion in February. The trade surplus increased from $9.1 billion to $11.8 billion, according to Central Bank figures. From January to March, the surplus was $18.6 billion, having fallen by $51.2 billion compared to the equivalent period in 2022.

What to watch next week:

- Consumer price dynamics and estimated inflation trends from the Central Bank (17.04)

- Central Bank overview of the regional economy (19.04)

- Inflation figures for the week from April 11-17 from Rosstat (19.04)

Further reading

What’s Really Going on Between Russia and China uncovers Alexander Gabuev

Is the Blossoming Relationship Between Russia and the UAE Doomed? argues Nikita Smagin

Steppe change: How Russia’s war on Ukraine is reshaping Kazakhstan examines Marie Dumuolin

Azovstal: A history Journalist Konstantin Skorkin tells the story of the steelworks that lay at the heart of Mariupol life