Kirill Dmitriev: Economic envoy, or political peace-maker?

Hello! This week we bring you a detailed look at Kirill Dmitriev — the Kremlin’s special envoy on economic talks with the United States who has been Moscow’s most high-profile negotiator with Donald Trump’s White House over restoring ties and ending the war in Ukraine.

Before we begin, though, a brief note from one of the authors of The Bell's Inside the Russian Economy newsletter, Alexandra Prokopenko:

I have been analyzing the Russian economy for 20 years, but I believe my work is more important now than ever. Russia is waging a major war in the center of Europe and trying to refashion the world order. Donald Trump has started a trade war against China, reshaping global trade. There will be no winners. But how will these things affect the Russian economy? Does Putin have enough money to continue waging war? Are sanctions working? Could fear of economic collapse force him to make concessions? A nuanced understanding of the Russian economy helps navigate this complicated puzzle.

From the beginning, our newsletter was designed to spotlight facts and figures, not ideological convictions and flashy headlines. While some commentators predicted Russia would collapse, we were analyzing the data and explaining why it was not that simple.

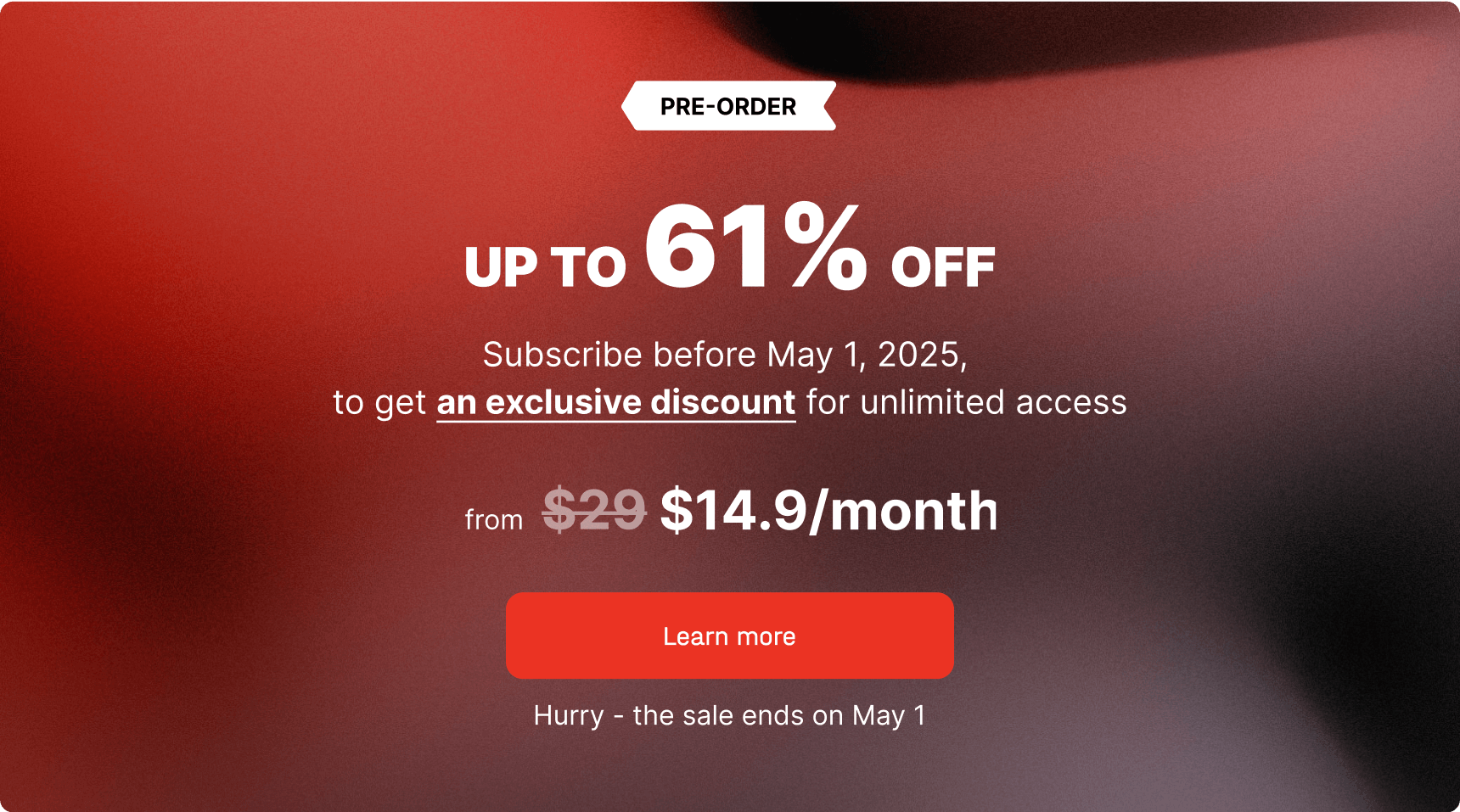

On May 1, The Bell in English will go behind a paywall. Such a decision is always a difficult one for authors and publishers, but expertise costs money, and we believe it’s the right choice. As a reader of our newsletter you can subscribe 20% less than even the cheapest option available via our website. I very much hope that you will opt to subscribe in order to continue reading – and enjoying – our analysis of the Russian economy.

Who is Kirill Dmitriev, Russia’s Trump whisperer?

While the world is focused on Trump’s trade war and Russian rockets kill dozens more civilians in Ukrainian cities, Donald Trump’s envoy Steve Witkoff again travelled to Russia, meeting Vladimir Putin in his home city of Saint Petersburg. On the Russian side, the organizer of the meeting and chaperone for Witkoff was Kirill Dmitriev, the head of the Russian Direct Investment Fund. The Bell has been following Dmitriev, who has become the most high-profile of the Russian negotiating team, for years. Here’s what you need to know about him:

Backchannels and Trump 2.0

Dmitriev’s involvement with Trump dates back to the Republican’s first term, when he set up a Russian-U.S. backchannel for discussions between Moscow and Washington. Using his connections in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, Dmitriev met with Trump's son-in-law Jared Kushner to try to push a restoration of U.S.-Russia relations. Though he had little success back then, Dmitriev has now been given a second shot as one of Russia’s top — certainly its most media-friendly — negotiators.

Shortly after Trump’s inauguration in January, Dmitriev again met Kushner and set up the first visible contact between Moscow and Washington — a visit to Russia by Trump’s special representative Steve Witkoff. Putin and Trump spoke on the phone the day after and then 10 days later Putin signed a decree officially assigning Dmitriev a new role as his special presidential representative “for investment and economic cooperation with foreign countries.”

Dmitriev has since then been involved exclusively in talks with the United States — both on an official level like as part of the Russian delegation at the most prominent negotiations with the Americans in Riyadh, and unofficially. The day after his appointment, Dmitriev started using a Twitter account that had lain dormant since it was set up in 2012. His tweets are all related to Trump and other themes calibrated to appeal to the U.S. president and his entourage. In a flurry of activity on the Elon Musk-owned site, Dmitriev has pompously heralded Trump’s speeches and applauded his tariffs, praised statements by J.D. Vance, cursed both the Europeans and Joe Biden, and proclaimed the dawn of a new era in U.S.-Russian relations.

A source close to the Kremlin told The Bell back in March that he was certain Dmitriev was simply acting as a liaison to set up initial contacts between the two countries and would then go on to take charge of economic projects, without any mandate to discuss a possible Ukraine settlement. At first, that seemed to be the case: Dmitriev promoted Russia’s rare earth metals, offered to work with Musk in exploring Mars and discussed the return of U.S. companies to Russia with the American Chamber of Commerce.

However, over the past week it has become clear that Dmitriev is playing a political role as well. During his trip to Washington, he met not only his official counterpart, Witkoff, but also Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Reuters reported that immediately after his meeting with Dmitriev, Witkoff told Trump that the quickest path to peace would be to hand Russia all four Ukrainian regions that it claims but has failed to occupy in three years of fighting.

Investment guru turned state capitalist

Dmitriev, who turns 50 in a few days, was born in Kyiv. “Not in Ukraine, in the USSR,” he told The Bell in an interview in 2021. Aged 17, he said his acquaintances encouraged him to apply for a grant to study abroad. Thus, as a young man, he found himself at California’s Foothill College, where he did well enough to earn a full scholarship to Stanford.

Graduating from Stanford in 1996, Dmitriev started work at consulting firm McKinsey, which, after a few years, funded him to study an MBA at Harvard. After completing his studies, he had offers from both McKinsey and Goldman Sachs, where he completed work experience during business school. Instead, he opted to move back to Russia and build his career there.

“Until now, money in Russia went to those who managed to grab a slice of the pie that had previously been in the hands of the state,” he said in a 2002 interview with National Geographic, just after he had returned to Russia. But now, “the pieces have been taken apart” and the oligarchs no longer risk taking them from one another, he said. Instead they want them to grow — “and for this they need good managers,” he said of his decision to return.

But it wasn’t working by working for Russian oligarchs that earned Dmitriev his reputation. He spent about a year with leading Russian IT company IBS, after which he was invited to become a director of the U.S.-Russian investment fund Delta Private Equity Partners, ultimately becoming co-managing partner. Delta Private Equity Partners managed two funds with a total value of around $500 million. The firm’s Delta Capital Fund became the most successful investment fund in Russia within a couple of years, securing 220% returns for investors.

After that success, Dmitriev finally found himself working with oligarchs — though not in Russia. In 2007 he returned to Ukraine as head of the Icon Private Equity fund, worth $1 billion. The fund’s investors were never disclosed and it wasn’t until two years later that it emerged there was only one shareholder, Ukrainian metals oligarch Viktor Pinchuk, son-in-law of the country’s second president Leonid Kuchma.

Dmitriev spent four years in Kyiv, in between the 2004 and 2014 revolutions. After returning to Russia, he told Vedomosti in a 2012 interview that he was unimpressed with his homeland, speaking of “so-called democratic changes” in Kyiv, rising corruption and “wild battles between democratic clans” which “devoured each other.”

Dmitriev sensed a career as an investment banker in Russia would be more profitable. Conflict with the West was only beginning to emerge and seemed far from inevitable. Dmitry Medvedev was the Russian president, and in the days before he spent his time composing bloodthirsty tweets, was seen as the most liberal West-leaning politician Russia had to offer. His government had plans to convert Moscow into an international finance hub. In 2011, Dmitriev became head of the newly-founded Russian sovereign wealth fund, the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), set up to attract Western investment. Dmitriev’s appointment made sense. “A Harvard man, really smart, with great communication skills. It was clear: he could happily talk to anyone,” one leading businessman told The Bell.

Sheikhs, the Sputnik vaccine, and Putin ties

While Dmitriev’s first fund, Delta Private Equity Partners, was widely seen as a model for the Russian market, question marks always surrounded RDIF. The fund itself was selective about the information it disclosed and from 2018, when the government allowed companies under threat of sanctions to stop publishing reports, it largely ceased doing so. The fund also struggled, having never received the levels of government money it was promised. After the first imposition of sanctions in 2014 in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, RDIF funding was cut. Over its first 10 years, the state put up just $4 billion of the promised $10 billion. Nevertheless, RDIF claims that alongside money put in by foreign partners, it invested $26 billion in the Russian economy.

Most of that cash came from the Middle East and China. It went towards hundreds of diverse projects in Russia — from billion-dollar sea ports, huge toll roads and rail bridges, to shares in private clinics and small retail chains. But the fund’s most high-profile project was bringing the Russian Covid-19 vaccine to global markets. The Kremlin hoped that Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine would be an important soft power weapon in its conflict with the West, especially in third countries (read more about this in our joint project with Meduza.)

In a nutshell, the vaccine was developed quickly and relatively successfully, but corners were cut in the regulatory approval process, meaning the vaccine always faced criticism over the studies underpinning its claims to be both safe and effective. Russia’s pharmaceutical industry also ran into big problems producing the vaccine on a mass scale, meanwhile the RDIF had difficulty getting it registered abroad. The fund’s supply contracts were significantly delayed and in some major markets, such as Brazil, Sputnik V lost its status as an approved vaccine due to its inability to meet local requirements. Dmitriev blamed “big pharma” in the West, claiming the likes of Pfizer and AstraZeneca had been tasked with crushing the Russian competitor.

Despite RDIF’s mixed success and the failure to roll Sputnik V out internationally, over a decade Dmitriev earned a reputation as an effective manager. More importantly he also grew close to Putin’s family. His wife, Natalya Popova, is a classmate and friend of Putin’s youngest daughter Katerina Tikhonova. She was also Tikhonova’s deputy at her Innopraktika fund. Dmitriev himself joined the board of trustees at Innopraktika and in the late 2010s was a member of the board at the Sibur chemical company, which was co-owned by Tikhonova’s then husband Kirill Shamalov.

Why the world should care

A cynical and effective investment banker like Dmitriev is the perfect candidate for the kind of win-win talks that Trump’s administration is trying to stage with Russia. All The Bell’s sources have always characterized him as a shrewd negotiator who knows how to charm his partners and build strong personal connections. But it remains entirely unclear how much independent authority he has been given, and whether he can help bring an end to the war that suits both Moscow and Washington.

PAID SUBSCRIPTION LAUNCH

From May 1, 2025, The Bell in English will no longer be free

From May 1, 2025, all The Bell’s newsletters and online content will be behind a paywall. We have taken this decision so that The Bell can remain financially independent, and maintain our high standards of journalism and economic expertise