Real incomes keep on falling

Hello! This is Alexandra Prokopenko with your weekly guide to the Russian economy — brought to you by The Bell. Today, I am joined by The Bell economy reporter Denis Kasyanchuk and we’ll look at what’s happening to incomes and living standards in Russia. What risks does the current situation pose for inflation and social stability? We’ll also look at what’s happening to the ruble and what that means for import substitution.

The risks of stagnating income and falling living standards

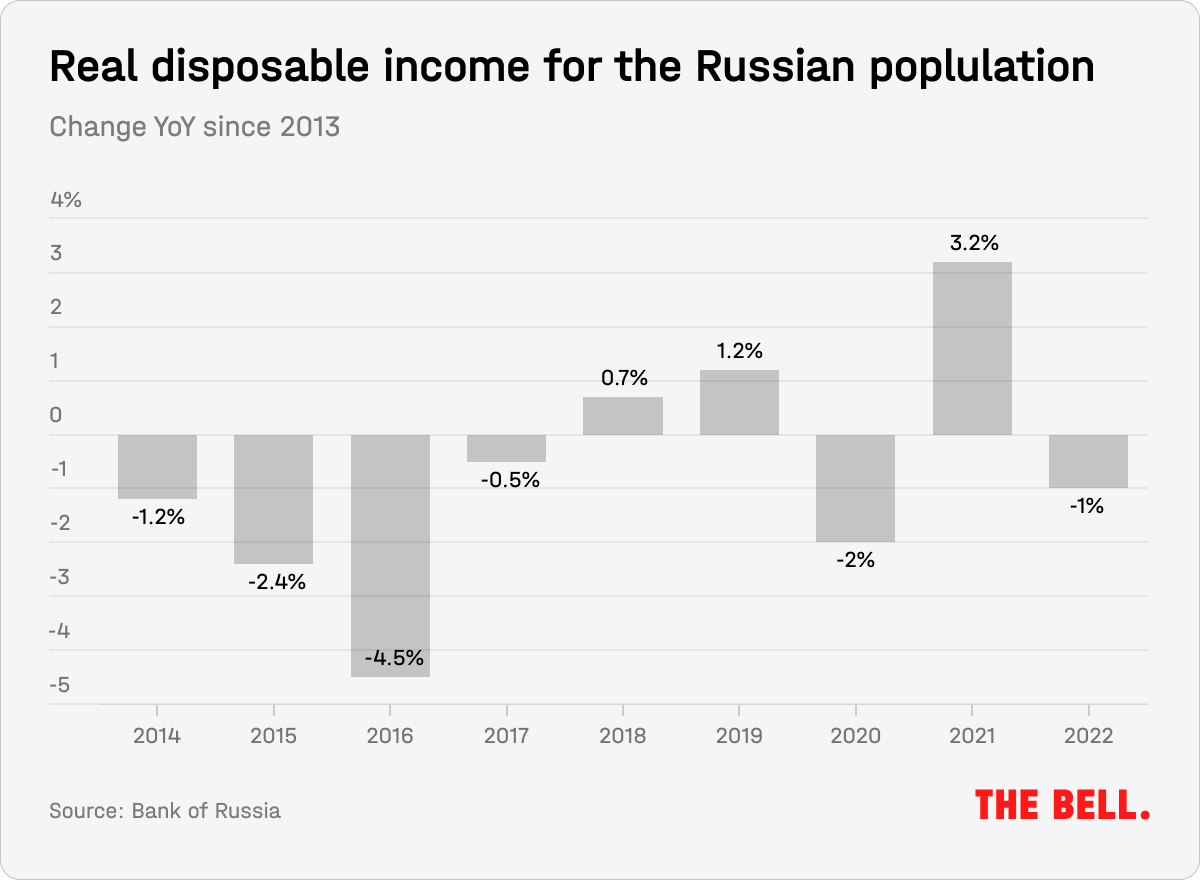

Household incomes are a sensitive issue for any government. For Russians, the last 10 years represent a “lost decade” in terms of real disposable income (i.e. income after mandatory payments and inflation-adjusted loan repayments). The last time Russians saw a consistent increase in household incomes was back in 2013. Since then, people have had to get used to wage stagnation. A Russian in 2023 is about 6% poorer than in 2013.

What happened to Russian incomes over the last decade?

From 2014 to 2017, incomes in Russia fell. In 2018, they showed near-zero growth (+0.1%) and then increased by 1% year-on-year in 2019. By the end of the pandemic in 2020, they were 11% down on 2013 levels. In 2021, incomes began to grow once more, but this was a consequence of pre-election payments from the state.

Last year, the fall in incomes was likely more than the official estimate (-1.1%) as official calculations do not include anybody working outside of large or medium-sized businesses. Economist Nikolai Kulbaka expects real incomes to fall this year at the same rate as in 2022. “The Russian economy is like a powerful, heavy ship that is sinking very slowly,” he said.

Incomes down, wages up

Russia finds itself in an unusual situation when it comes to employment and wages. As a rule, Russia’s labor market responds to crises by reducing salaries while preserving jobs – we saw this in the 1990s and in 2014-15. Instead of laying off staff, Russian employers prefer to cut wages or put people on extended, unpaid leave.

Last year, however, average salaries did not fall. Instead, they rose — despite record low unemployment (3.5% according to the latest official figures). In January, the average nominal monthly salary was 63,260 rubles ($781), up 12.4% compared with the same month a year earlier. This odd situation is the result of Russian businesses facing a labor shortage following mobilization for the Ukraine war. To retain staff, they have been forced to increase salaries. We wrote more about what is happening on the labor market in a recent newsletter.

Salaries rose fastest in 2022 in the following sectors:

- Manufacture of computers and electronics — +25.8%

- Public administration and military security — +22.7%

- Specialists in pipeline transport — +20.9%

- Railway transport — +20.6%

- Salaries in manufacturing industries — +16.1%

The highest salaries now are:

- Oil and natural gas workers (161,000 rubles a month, +7%)

- Air and space transport (142,528 rubles a month, -0,9%)

- Tobacco production (130,813 rubles a month, +6%)

Lowest salaries now:

- Clothing manufacturing (28,273 rubles a month, +17%)

- Leather (35,541 rubles a month, +7,3%)

- Furniture (37,378 rubles a month, +8,7%)

The impact of social handouts

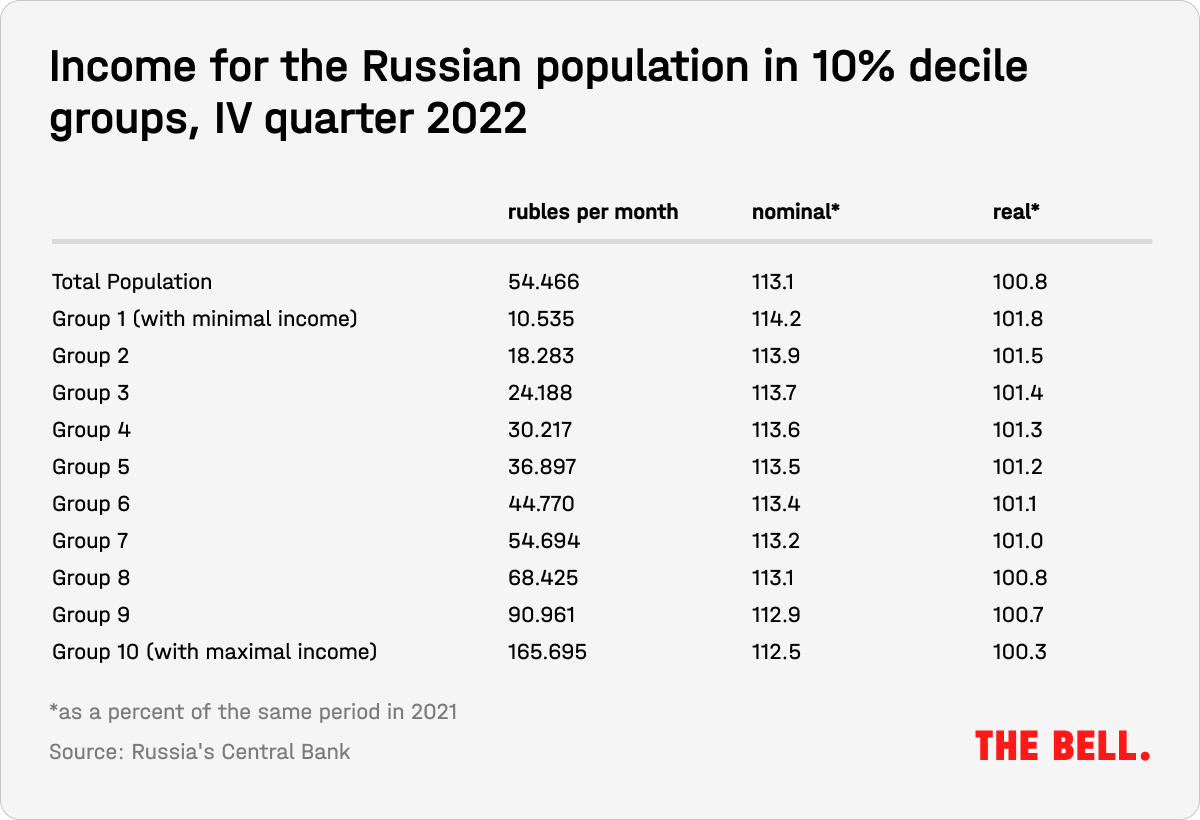

Last year, for the first time, Russia began publishing data about how incomes are distributed among different parts of the population. These figures are based on information from the Tax Service, the Social Fund, the Central Bank, credit organization and others. They make it possible to assess the incomes of different social groups.

It shows that the poorest Russians are seeing their salaries increase faster than the wealthiest — mostly due to increased welfare payments, benefits and one-off payments (for example, to soldiers injured in Ukraine). In the last three months of 2022, salaries for this group were up 1.8% compared with the equivalent period in 2021. That’s six times more than the income growth of the “wealthiest” group, which was up just 0.3%. In absolute terms, the per capita income of the “poorest” group was 10,535 rubles ($130), while the “wealthiest” group earned 165,695 rubles ($2,046).

The state spent 4.7 trillion rubles on social payments in the last three months of 2022, up 13.1% on the same period the year before. However, welfare payments are playing a slightly lesser role in overall salaries than in coronavirus-afflicted 2021. Payments have been more carefully targeted and favor low-income families with children, said Alexander Isakov of Bloomberg Economics. Incomes among the middle class barely increased in the last quarter of 2022 (ranging from 0.7% to 1%). While the government supports the poor, the middle class is left to fend for itself, explained expert Natalia Zubarevich.

Increased welfare payments in Russia have reduced poverty levels to record lows, according to the State Statistics Service (Rosstat). Its calculations suggest that, in 2022, the number of Russians below the poverty line fell by 0.7 million people — making up 10.5% of the population. That’s the lowest figure since records first began in 1992.

However, when talking about social handouts, it’s worth remembering that this includes compensation for soldiers injured while fighting in Ukraine and payments to bereaved families. Each of these payments is several million rubles. In addition, everybody mobilized to fight in Ukraine receives a one-time payment of 195,000 rubles ($2,388).

Inflation risks

Some predict real incomes could enjoy double-digit growth this month and, for 2023 as a whole, many believe income growth could reach 5%. This means that the warnings of Central Bank chairwoman Elvira Nabiullina look set to come true and wage growth will significantly exceed labor productivity. And that increases the risk of inflation: firstly, because businesses will pass increased labor costs into prices and, second, because the population will switch from saving to spending.

Bloomberg Economics anticipates the strong growth in labor costs seen in 2022 will continue this year in all private companies (apart from in the financial sector). What will happen next can be seen in Russia’s stagnant construction sector (many builders were mobilized and sent to Ukraine). The sector’s labor shortage has since eased, but only at the expense of cutbacks, output and prices. In the long term, this process will have significant consequences for the Russian economy’s potential growth.

Why the world should care

In the absence of a collapse in incomes or abrupt declines in standards of living, it’s easy to understand why most Russians are passive about the war. It can be summed up in the phrase: “negative stabilization.” Things are not bad enough to spark protests and there is more money available — albeit due to mobilization and an imbalanced labor market. However, income growth is something ordinary Russians are unlikely to see for many years.

The ruble on a rollercoaster ride

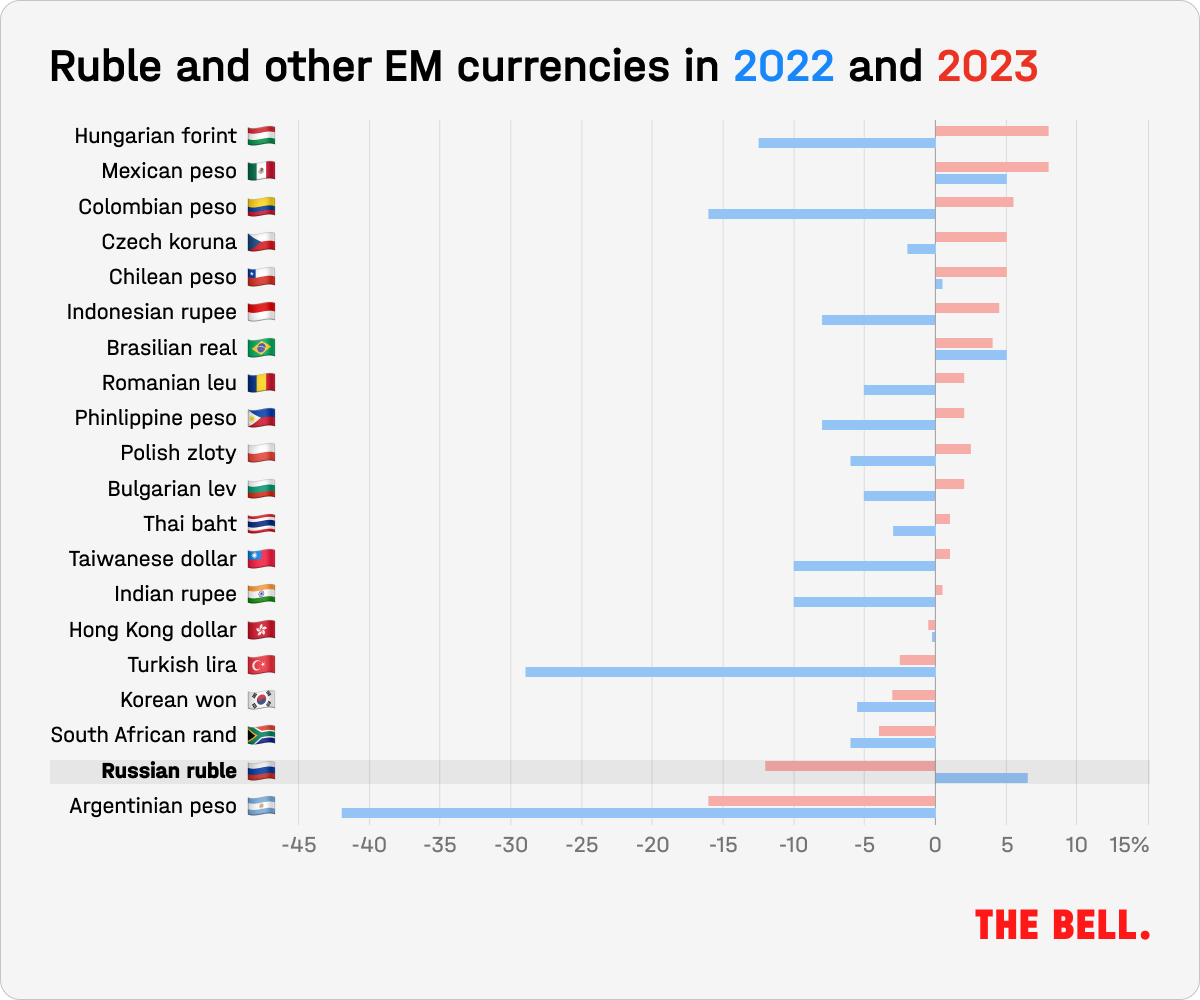

In April, the ruble recorded the worst performance of any developing country currency. By 13:50 on Thursday it had passed 81 rubles to the U.S. dollar for the first time since April 15 last year. It hit the psychological mark of 80 rubles to the U.S. dollar the previous day.

Finance Minister Anton Siluanov linked the ruble’s fall to a reduction in foreign currency inflows from exports and an increase in imports: “In recent months, trends have swung from one to another,” he said. He expressed hope that the ruble would strengthen due to rising oil prices. However, there is a time lag before this will buoy the currency.

Another reason for the sudden weakening of the ruble could be foreign companies selling their Russian assets. It emerged on Wednesday that oil major Shell might be able to take $1 billion out of Russia. As well as Shell, other companies could follow suit: for example, Tatneft’s buy-out of Nokian Tyres or Gazprom’s purchase of Salym Petroleum.

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian currency market would hardly have reacted so strongly to this kind of outflow – its daily turnover was five times greater than now. However, without non-residents and isolated from global capital markets, even small volumes can influence the exchange rate.

Although the ruble fell below 80 to the U.S. dollar, analysts are not rushing to revise their projections and still expect the exchange rate this year to be in the 75-80 range against the U.S. dollar. “The ruble is close to its localized low point and in the near future I expect to see it stabilize or even climb,” said Loko-Invest’s director of investments Dmitry Polevoy.

The main problem is actually not the dollar rate itself, but the dramatic fluctuations. The implied monthly volatility calculated on April 4 reached 30%.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, when the Russian authorities stopped publishing trade data, the ruble’s worth has become the leading indicator of Russia’s international economic isolation. Currency volatility last spring after the invasion was the greatest ever seen. Exchange rates swung by as much as 10% in a single day, a level normally associated with toxic third-tier securities or crypto-currencies. When the ruble eventually strengthened to as much as 50 against the U.S. dollar, it was reflecting a record trade surplus and a collapsing import market.

Russia’s trade surplus is expected to normalize in 2023. In addition, the Finance Ministry is selling off yuan from the National Wealth Fund to smooth over volatility. In the coming months, there are plans to sell 74.6 billion rubles’ worth of yuan.

Why the world should care

In one of her first interviews as head of the Central Bank, Nabiullina said: “a strong economy has a strong exchange rate.” But it becomes difficult to talk of a strong economy when the currency is subject to 30% volatility. In the long term, this weakens the ruble’s payment and savings functions as economic agents set higher costs and postpone investments. And this makes the ruble less attractive as the world transitions to trade in national currencies.

Figures of the week

- Ministry of Finance reported a surplus of the federal budget in March at 181 billion rubles. In January-March, the budget deficit stood at 2.4 trillion rubles; income at 5.68 trillion, expenditures at 8.08 trillion. Non-oil and gas revenues decreased by 4%, to 4.042 trillion rubles. Oil and gas revenues collapsed by 45%, to 1.635 trillion rubles, due to low price of Urals oil and reduced natural gas export. Budget expenditures increased by 34%.

- Russian GDP grew by 0.5% in Q4 2022 q/q, Rosstat reported. Oil and gas sector's share rose to 18.1%, the highest since 2019.

- In 2022, Russia’s largest private bank, Alfa Bank, recorded a loss of 117.1 billion rubles. That’s the biggest loss in the bank’s history. The last time the bank recorded a loss was in 2009, when it was 3.35 billion rubles in the red.

- Weekly inflation for March 28 – April 3 accelerated to 0.13% from 0.05%, according to Economic Development Ministry figures. Annual inflation slowed to 3.29%.

- On April 4, for the first time, Russian banks purchased 2.8 billion yuan from the Central Bank for 31.8 billion rubles. The deal was conducted via a currency swap mechanism that had not previously been in demand. The currency swap was first used on March 24, but only for the small sum of 4.8 million yuan (53.4 million rubles). Interest in Central Bank currency swaps suggests “yuan depletion” on the markets, with banks unable to secure the necessary volumes of Chinese currency from each other.

- As of April 1, the National Wealth Fund stood at just under 12 trillion rubles, equivalent to 7.9% of GDP, the Finance Ministry reported. In March, the fund increased by 799.66 billion rubles. Last month saw sales of 7.479 billion yuan and 11.863 tons of gold from the fund — to cover February’s budget deficit. On April 1, the fund’s liquid assets stood at the equivalent of 6.712 trillion rubles ($87.07 billion) — on March 1, this figure was 6.446 trillion rubles ($85.457 billion). This increase is primarily due to a rise in Sberbank’s share prices that has been driven by announcements of upcoming dividends.

- Oil and gas revenues in March were 688 billion rubles (up 32% from February but down 42% year-on-year), the Finance Ministry said. Of this, 221 billion rubles came from an additional income tax on extraction. The average price for a barrel of Urals crude fell from $49.56 to $47.85 in March.

What to look out for next week

- Central Bank’s overview of risks on the financial markets (April 10)

- Central Bank’s estimate of inflation trends (April 12)

- Estimated balance of payments Q1 2023 (April 11)

- Monthly figures for Russia’s international trade in services (April 12)

- Russia’s international trade in goods for Feb. 2023 (April 14)

- Inflation in Russia in March (April 12)

- Inflation in Russia from April 4-10 (April 12)

Further reading

- What’s Behind the Posturing of Russian Mercenaries in the Balkans? — Maksim Samorukov

- The art of vassalisation: How Russia’s war on Ukraine has transformed transatlantic relations — Jeremy Shapiro and Jana Puglierin

- How to think about a post-Putin future? — Andrei Yakovlev believes that it is necessary to begin to develop a new socio-political and economic model for Russia after Putin

- Blundering on the Brink — Sergey Radchenko and Vladislav Zubok tell the secret history of the Cuban missile crisis