THE BELL WEEKLY: Putin’s implausible landslide

Hello. This week we dig into Vladimir Putin’s inevitable election victory. We cover the official results, claims of manipulation and how the Kremlin orchestrated the “record” figures. We also look at an escalation in Ukrainian attacks on the eve of the poll and analyze the opposition’s attempts to disrupt Putin’s re-election.

‘Record’ victory cements Putin’s autocrat status

Vladimir Putin was re-elected as Russian president. Officially it’s his fifth term in the Kremlin — although in practice it’s six if we include his stint pulling the strings as prime minister. The official results have Putin polling even higher than predicted, taking 87% of the vote. That figure looks utterly implausible and places Putin among the likes of Asian, Middle Eastern and Central Asian autocrats. The election itself went ahead against a tense background, with Ukrainian shelling and attempted incursions into Russia’s border regions along with on-going drone attacks on Russian oil refineries.

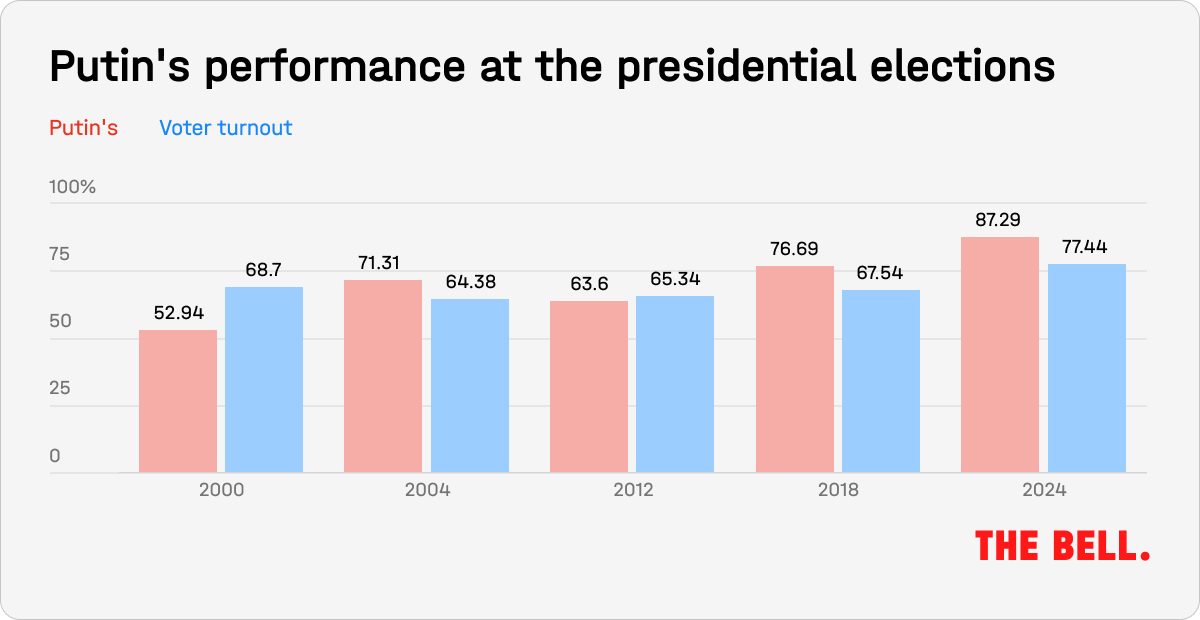

- The official election result is already out — Vladimir Putin secured 87.28% on a turnout of 77.44%. Both those numbers are record highs since the collapse of the Soviet Union. And both are about 10 percentage points up on 2018 (when Putin polled 76.8% on a 67% turnout). This suggests that the Kremlin’s political managers were tasked with delivering a significant increase in Putin’s popularity. That in itself is not surprising: in the current circumstances an autocrat needs to demonstrate how his people have rallied around the flag.

- Initial research by journalists and independent experts suggests the vote could have been the most heavily falsified in the history of post-Soviet Russia. Analysis by IStories and Ivan Shukshin, a researcher and activist with the Golos vote monitoring NGO, estimated that around 22 million of the 76.3 million votes cast for Putin were “anomalous.” In other words, almost a third of Putin’s official tally could have been false.

- Their methodology is based on analyzing the turnout and vote shares at individual polling stations, using the central election commission’s official data. Districts with higher turnouts also have larger vote shares for Putin — a fact which suggests ballot-stuffing since the two shouldn’t be strongly correlated. IStories and Shukshin didn’t include results in Moscow, where online voting makes the analysis trickier. A third report by Novaya Gazeta Europe said as many as 31.6 million votes — almost half of Putin’s total — could have been fake.

- Many experienced observers of Russian politics (1,2) believe that election organizers in provincial Russia “overdid it” this time round. Most pre-election leaks of the Kremlin’s vote strategy featured more modest targets. In spring 2023, for instance, RBC wrote that the Kremlin wanted to secure 75% of the vote on a 70% turnout. A few months later, Meduza wrote that regional authorities were advised that they should secure at least 80% of the vote for Putin. The final pre-election opinion polls conducted by state pollster VTsIOM (which also represent indirect instructions to regional election officials for polling day) showed Putin’s result was at the initial target level of 75%.

- The record result places Putin firmly among his fellow autocrats. In free democratic elections, it’s a rare anomaly for a candidate to poll even at 60-70%. Only once, in extreme circumstances, have we seen more than 80% in a democratic country — a huge protest vote that gave France’s Jacques Chirac 82% in a presidential run-off against Jean-Marie le Pen in 2002, the BBC reported. In Russian history, Putin still has something to aim for if we look back to Soviet times. The turnout in 2024 was slightly higher than when Boris Yeltsin was voted president of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1991, but there is still some way to go to match the Stalin era of 100% turnout in votes to appoint new deputies.

- Since Putin was re-elected in 2018, voting in Russia has become even less transparent, and offered greater opportunities for fraud. Remote electronic voting was conducted in 29 Russian regions. Some 70% of the 4.7 million voters registered to vote online apparently cast their votes on the first of the three-day poll. Monitoring violations at physical polling stations is an almost impossible task. The Central Electoral Commission stopped broadcasting live footage from monitoring cameras in polling stations after the pictures from 2018 had depicted numerous violations and led observers to conclude that the scale of ballot stuffing was so great that the real result could not be determined in at least 11 regions.

- The 2024 poll also differed from Putin’s two most recent victories in the selection of candidates who ran against the Kremlin leader. In 2012, political strategists allowed businessman Mikhail Prokhorov to stand, proposing that Russia’s marginal liberal opposition would consolidate around him. And in 2018, that same role went to TV presenter Ksenia Sobchak. But this time round there was no acceptable liberal candidate. Even the little-known politician Boris Nadezhdin, who timidly spoke out against the war in Ukraine, was denied registration. On the ballot were only Putin’s “rivals” from the systemic opposition parties. All of them have been equally supportive of Russia’s repressive turn, backing various crackdown measures that have come before the State Duma in recent years.

- The extras in the 2024 race — Communist Nikolai Kharitonov, Vladislav Davankov of New People, and Leonid Slutsky of the LDPR — polled less than 12% combined. That’s slightly less than communist candidate Pavel Grudinin managed on his own in 2018. The 75-year-old Kharitonov’s 4.3% was better than the youthful Davankov’s 3.8%, while Slutsky, the unsuccessful heir to charismatic populist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, trailed in last with 3.2%.

The Bell is now listed as “a foreign agent” in Russia: our website is blocked, we can no longer raise money through advertising, and our business model is in ruins. Journalists in Russia face greater risks than ever before. Repressive new laws threaten up to 15 years in jail for objective reporting.

However, we are not about to give up. This newsletter is our newest project. It presents an in-depth analysis of the Russian economy, which has survived the first year of the war but is becoming ever more secretive. We will try and shed some light on what’s going on. Each edition will tackle a part of the big question: how long can the Russian economy endure under sanctions and when will the Kremlin run out of money for its war?

We don’t want to have to charge a fee for our newsletters. However, if The Bell is to continue its work, we need your support.

You can make a donation here. It will help our journalists continue investigating stories, breaking news and publishing newsletters.

A background of shelling

This was the first major Russian election since the invasion of Ukraine, and the Ukrainian military did all it could to overshadow polling with rocket attacks and artillery bombardments of Russian territory. Pro-Kyiv sabotage groups attempted armed raids across the border, and there was also an escalation in drone attacks.

- From March 12-14, three pro-Kyiv groups — the “Free Russia Legion”, the “Russian Volunteer Corps” and the “Siberian Legion” — attempted to launch raids from Ukrainian territory into the Belgorod and Kursk regions. All three groups were established in Ukraine with the support of the local security forces. However, unlike last May’s raid, when saboteurs successfully crossed the border and spent almost a day roaming through Russian settlements, this time the Russian military managed to halt them at the border.

- Alexander Khodakovsky, an active military blogger and Russian military commander in Moscow-controlled Donetsk, claimed that Russian intelligence knew about the planned raid and had prepared border patrols and servicemen to stop it. That could explain the lack of success from the Ukrainian side despite the use of heavy armored vehicles and a helicopter landing close to the border (on Thursday, Russia’s defense ministry said it had destroyed the helicopter). At the same time, the supposed casualty figures released by Russian military sources seem unrealistic: they claim 500 dead and 1,000 wounded with the loss of 18 tanks and 23 armored vehicles. There is no independent confirmation of these figures.

- In Washington, the Institute for the Study of War noted that since last year’s cross-border raid (and the Wagner mutiny), the Kremlin has largely cleared the information space, ensuring that war correspondents and military bloggers were unable to question the competence of Russia’s military leadership this time.

- Ukrainian forces also shelled the border cities and towns of Belgorod, Grayvoron and Shebekino, damaging buildings and leaving several people dead or wounded. There was a selective evacuation of some border settlements in Belgorod, which also closed shopping centers and schools for a few days.

- The greatest damage in recent days came from drone attacks on major Russian oil refineries. A Lukoil plant in Nizhny Novgorod and Rosneft’s facility in Ryazan were hardest hit. Primary oil fractionation units were damaged at both sites, which could bring a 5-9% fall in Russia’s overall gasoline production. Wholesale prices for diesel and gasoline went up 6% after the strikes, although consumer prices are stable for now. All this is happening at the start of the agricultural sowing season and with peak summer transport use on the horizon. The full extent of the damage is not yet known. Repairs could take a couple of months, or more than half a year.

- It's hard to defend refineries against these attacks. These installations are large, stationary targets. Drones do not need external controls, just good, noise-free navigation. Reliable air defense for a plant that covers several square kilometers would require a lot of military resources, which are in short supply even on the front lines.

The opposition’s approach

The Russian opposition saw its organizational structures demolished even before the war. As a result, there weren’t many options for what they could do during this contest. They adopted two main tactical approaches.

- The first, backed by Alexei Navalny’s supporters, called for a significant election-day quasi-protest. Called “Noon against Putin,” opponents of the ruling regime were urged to arrive at their polling stations at exactly midday and form long lines outside. It was presented as a way to express dissent without the risk of arrest for attending an unsanctioned protest. This is a characteristic move for Navalny’s team: in the absence of any opportunity for supporters to gather legally, they have long focussed on protests intended to clearly demonstrate the number of people who disagree with the regime, while minimizing the risks of a police response.

- As a result of the protest, there were long lines at polling stations in Russia and especially at Russian consulates abroad, where thousands of Putin’s opponents gathered. Moscow activists estimate that in the capital more than 230,000 people went to a “Noon against Putin” protest. It is not clear exactly what this figure means for the opposition movement or if these people can be further mobilized against Putin and the regime.

- As expected, Russian propaganda outlets, the foreign ministry and individual Russian embassies happily posted pictures of the lines outside polling stations to spread their own message (1, 2, 3, 4) — one of an apparent groundswell of popular support for the election and record-high turnout.

- The second tactic adopted by the opposition was to encourage people, once in the ballot booth, to vote for any candidate except Putin in the absence of a genuine candidate to rally around. Different figures backed slightly different approaches. Opposition politician Maxim Katz, for example, urged people to vote specifically for New People’s Vladislav Davankov as the only “conditionally liberal” candidate. Navalny’s team used a random number generator to select their preferred candidate. As the official election figures suggest, this had little impact on the eventual result.

- According to rights monitor OVD-Info (which Russia has targeted and named a foreign agent), 86 people were arrested in 20 cities on March 17, the final day of voting. Over the three days, it recorded more than 100 arrests — slightly more than during the one-day 2018 vote, when opposition observers and picketers were detained. Vote monitor Golos (also listed as a foreign agent) reported 1,719 violations on March 17. Confirmed reports of ballot stuffing were rare, almost certainly as a result of strict limitations on the powers of observers, the end of polling station filming, and an almost complete absence of external controls over the handling of ballot papers.

What happens next?

Putin’s victory was inevitable — as was the fact that the opposition had no serious means of influencing the vote. The result that Putin claimed could indicate that he wants to move even further down the autocratic model and become more like some of his peers in Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East — not just in terms of election results, but also the approach of his regime. We will know more about this in the next six weeks, from his first post-election speeches and, more importantly, from the make-up of the new government that will be installed after his official inauguration. We wrote about possible changes in the government here.